Kyungho Nam

–

–

Korea Hydro & Nuclear Power Co., LTD.

Central Research Institute

Safety Analysis Group

Deajeon, Republic of Korea

–

Article

–

–

–

Study on verification of SPACE code based on an MSGTR experiment at the ATLAS-PAFS facility

1. Introduction

1.1 Background

Following the Fukushima nuclear disaster in 2011 and based on the lessons learned from the accident, there have been many changes to the relevant safety design criteria and/or regulations around the world. The Nuclear Safety and Security Commission (NSSC) in Korea has required plant-specific accident management plans, which extend beyond design basis accidents to include severe accidents. The revised regulation in Korea has determined a list of multiple failure accidents that must be considered for any accident management plan [1]. Multiple failure accidents should be considered for Design Extension Conditions, which is defined by the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) Specific Safety Requirement [2, 3].

The Multiple Steam Generator Tube Rupture (MSGTR) accident is selected as one of the multiple failure accidents by the Korean NSSC, and it is defined as an accident in which more than five U-tubes of a steam generator rupture. In a MSGTR accident, the pressurized primary coolant leaks into the secondary system and thus exposes radioactive material. Therefore, it is important that the extent of the leak is limited and that the pressure drop across the break be kept as low as possible to reduce the radioactive release. Compared to single tube rupture, MSGTR causes quicker depressurization of the reactor coolant system (RCS) and places greater demand on the inventory makeup process.

To elucidate the thermal hydraulic process of the MSGTR accident, an experimental study using the Advanced Test Loop for Accident Simulation (ATLAS) facility was conducted by the Korea Atomic Energy Research Institute (KAERI) [4]. The experiment simulated the rupture of five steam generator tubes, and the results showed that the Passive Auxiliary Feedwater System (PAFS) adopted in the Advanced Power Reactor Plus (APR+) had sufficient cooling capacity to mitigate the accident. The PAFS is one of the advanced safety features of a passive cooling system that allow it to replace a conventional active Auxiliary Feed-water System (AFWS) [5]. In a typical Nuclear Power Plant (NPP), a motor-driven or turbine-driven auxiliary feedwater is supplied after the wide-range water level of a steam generator is decreased below the low steam generator level. However, to confirm the cooling capability of PAFS compared to that of AFWS, an experimental scenario was conducted in which the PAFS was supplied to an intact SG instead of auxiliary feedwater. The PAFS is a passive system capable of condensing the steam generated in a steam generator and feeding the condensed water to the steam generator using gravity.

For current safety analyses of Korean nuclear power plants, thermal-hydraulic safety analysis codes supplied by foreign vendors such as Westinghouse and Combustion Engineering have been used. The Ministry Of Trade, Industry and Energy (MOTIE) in Korea launched the ‘Nu-Tech 2012’ project to improve the competitiveness of the Korean nuclear industry in 2006, and the Korean nuclear industry developed the SPACE (Safety and Performance Analysis CodE for nuclear power plants) code [6]. This code was approved by the Korean NSSC in 2017, and it will replace outdated vendor-supplied codes and will be used for safety analyses of operating nuclear power plants in Korea as well as the design of advanced reactors. While the SPACE code will mainly be used in safety analyses, the code with best-estimate capabilities will be able to cover performance analysis as well. The programming language for the SPACE code is C++, and this code adopts the advanced physical modeling of two-phase flows, namely two-fluid three-field models which comprise gas, continuous liquid, and droplet fields.

According to the General Safety Requirement (GSR) of IAEA, any calculation method and computer codes used in safety analysis must undergo verification and validation [7]. Further, verification calculations of system tests or integral tests are used to validate the general consistency of the revision [8]. Therefore, a verification calculation based on integral effect experiments is needed to improve the reliability of the prediction results of the SPACE code. In particular, the multiple failure accident condition is the new safety design criteria, so the verification process should be performed. To this end, the first objective of this study is to verify a multiple failure accident calculation capability of the SPACE code, while the second objective is to confirm the transient phenomena of MSGTR and the cooling effect of PAFS during MSGTR with respect to the first objective, as mentioned above. The heat loss phenomenon is a measure of the total heat transfer of heat from either conduction, convection, radiation, or any combination of these. Newton’s law of cooling states that the rate of heat loss of an object is directly proportional to the difference in the temperature between the object and its surroundings. Under the experimental conditions of high temperature and high pressure, the heat loss is particularly likely to increase because of the temperature difference between the experiment component and the surrounding atmosphere. This physical phenomenon can affect the heat transfer experiment, and it plays an important role in the performance of the system. The heat loss is a function of area in accordance with the convective heat transfer equation. According to the design document, the ATLAS facility has a relatively large surface area to volume ratio which is in accordance with the design characteristic [9]. For this reason, additional work to confirm the heat loss effect on the ATLAS-PAFS facility was also conducted to confirm the heat loss effect on the system behavior of the integral test facility.

1.2 A brief description of ATLAS-PAFS facility

As mentioned previously, KAERI has been operating an integral effect test facility, ‘ATLAS’, for the transient and accident simulation of a Pressurized Water Reactor (PWR) [10]. The reference plant of ATLAS is the APR1400, which has been developed by the Korean nuclear industry. ATLAS has the same two-loop features as the APR1400, and it is designed using the scaling method to simulate various test scenarios as realistically as possible [9, 10]. This test facility also includes design features of the OPR1000, which is Korean standard NPP, such as a cold-leg injection mode for safety injection and a low pressure safety injection mode.

As mentioned above, the PAFS is one of the advanced passive safety systems adopted in the APR+, and an experimental program is currently underway at KAERI to validate the cooling and operational performance of the PAFS [11]. The main objective of the ATLAS-PAFS integral effect test is to investigate the thermal hydraulic behavior in the primary and secondary systems of the ATLAS during a transient at which PAFS is actuated. The PAFS facility is described in further detail below.

2. Description of ATLAS-PAFS model for MSGTR scenario using SPACE code

2.1 Experiment scenario

To validate the prediction capability of the SPACE code, the experimental information provided by KAERI was utilized [4]. The target scenario for the experiment is a MSGTR with a PAFS operation occurrence and asymmetric cooling. To initiate the MSGTR transient, first, the break valve at the SGTR simulation pipe line is opened. By opening the break valve, the primary system inventory was discharged from the hot side of the lower plenum to the upper location of the steam generator secondary hot side. Next, the primary system began to be depressurized and the secondary side water level of the steam generator increased. At the same time as the HSGL signal occurrence, reactor trip occurred, and the core power started to decrease following the decay curve. For the transient calculation, the decay power curve was considered along with the tables for time versus power. The main feedwater isolation valves (MFIVs) and the main steam isolation valves (MSIVs) for two steam generators were closed after delay times. The main steam safety valves (MSSVs) on the steam line opened due to the pressure increase of SG-1, and these valves were kept in cyclic operation of opening and closing to protect the primary and secondary systems from over-pressurization. The accident caused the depressurization of RCS and resulted in a Low PZR Pressure (LPP) signal. Further, the Safety Injection Pumps (SIPs) began after delay times. It was assumed that only one safety injection pump per train was operated for the experiment scenario. In accordance with this assumption, SIP-1 and SIP-3 were available. The injection flow rate was applied using pressure – mass flow curve based on experiment data. To simulate an accident management measure based on the cooling performance of PAFS during a MSGTR, the PAFS was supplied to an intact SG-2 instead of auxiliary feedwater after the water level of the SG-2 fell below the PAFS operation set point due to the decay power. It was also assumed that the auxiliary feed water system would not work for the assessment of PAFS cooling capability. After the initiation of the PAFS, the decay heat was removed from the RCS by the natural convection of the PAFS. Finally, the whole system was cooled down in a stable manner with the successful operation of SIPs, MSSVs, and PAFS.

2.2 Brief overview of model information

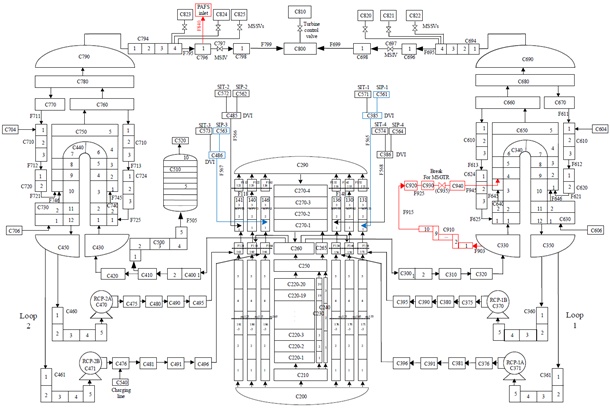

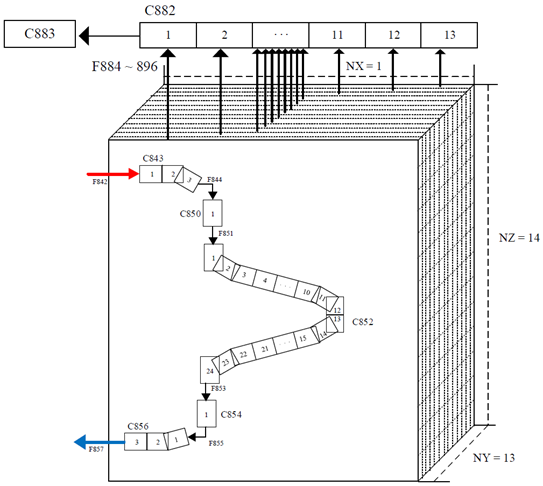

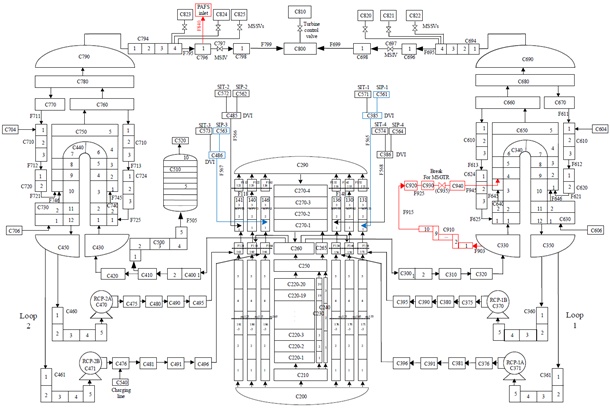

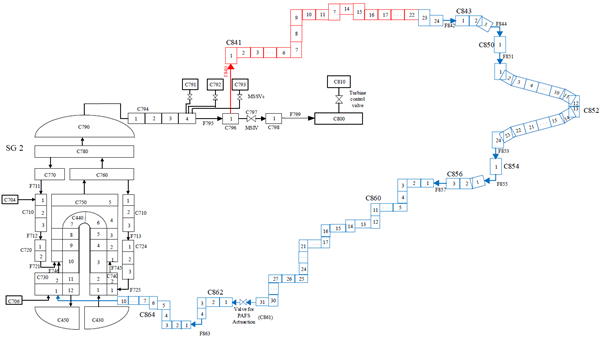

For the experimental simulation, the ATLAS-PAFS test facility was modeled using SPACE code as shown in Fig. 1. In the calculation, the decay power was imposed in accordance with the experiment, and the operation logics of the safety systems, such as safety injection and PAFS, were reflected. The geometrical and material information of the components and pipe lines in the ATLAS-PAFS test facility was also reflected [9, 12]. The reactor vessel was separated to simulate the core, bypass flow, reactor vessel lower plenum, and the reactor vessel upper head. The core model included the top and bottom inactive core regions, average channel, and hot channel. The safety injection system had four independent trains and a direct vessel injection (DVI) mode. Each train of the safety injection system consisted of safety injection pumps (SIPs). Injection lines could be aligned to either reactor vessel down-comer for DVI injection. The pressurizer was modeled as a single component with 10 vertical nodes. The lower part was connected to hot leg through a surge line separated into five nodes. The hot legs and cold legs were modeled with four cells each, while the intermediate legs were modeled with five nodes. The steam generator included five nodes for the evaporator and two nodes for the economizer. The main steam safety valves were modeled into three separate groups; each group was operated on a different set point of pressure in the steam generator dome.

2.3 SGTR simulation facility

The geometry of the ATLAS facility, which was composed of a SGTR simulation pipe and connected with a PAFS facility, was modeled as shown in Fig. 1. In the ATLAS facility with the SGTR simulation pipe, the primary system inventory was discharged from the hot side of the lower plenum to the upper location of the SG-1 secondary hot-side to simulate a MSGTR accident. It is composed of a break simulation valve, an orifice flow meter, an orifice, and break nozzles. The ‘PIPE’ component option of SPACE code was used to model the upstream pipe, which was part of the SGTR simulation pipe; this pipe section was geometrically divided into 10 nodes. The break nozzle was installed to simulate a five-tube rupture with a non-choking orifice. This tube section is modeled using the ‘CELL’ component option of SPACE code. The input of the inner diameter is 1.756 mm and the total flow area is the summation of the five-tube area. An orifice with a 1.68mm hole was installed at the end of the break nozzles to simulate the choking flow condition at tube rupture, and the break nozzles were designed to maintain the equivalent pressure drop in the case of the non-choking flow condition. The mass flow rate through the SGTR simulation pipe was measured using an orifice flow meter. These orifice and orifice flow meter sections were modeled using the ‘FACE’ component option of SPACE code. The experiment began by opening an initiation valve to simulate a MSGTR on the SG-1. This valve was modeled as the ‘TRIP VALV’ component option of SPACE code, and it was opened at the start of the transient calculation. The MSGTR occurs on the tubes of SG-1, which are connected to the SGTR simulation pipe; five break nozzles are opened in total [4].

2.4 Passive Auxiliary Feedwater System (PAFS)

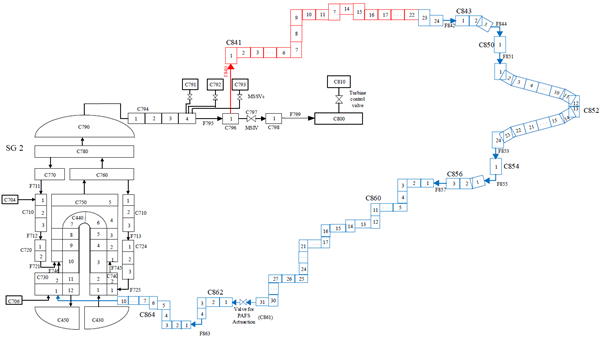

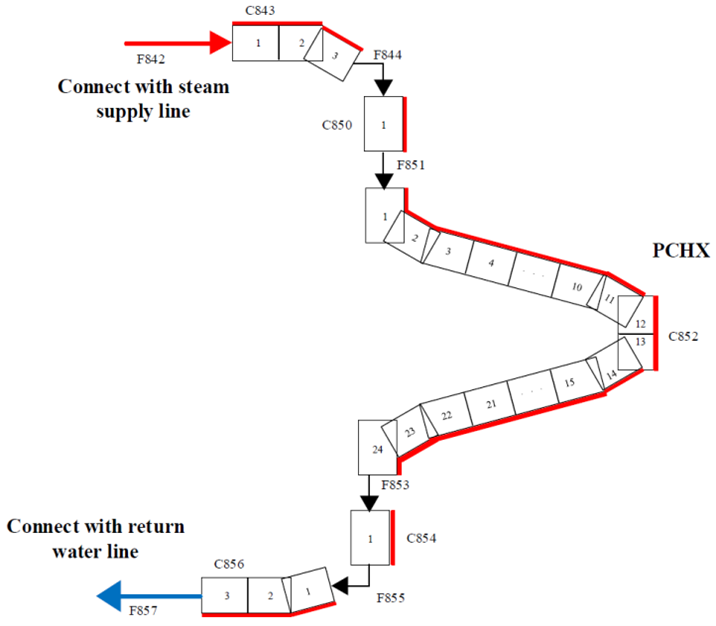

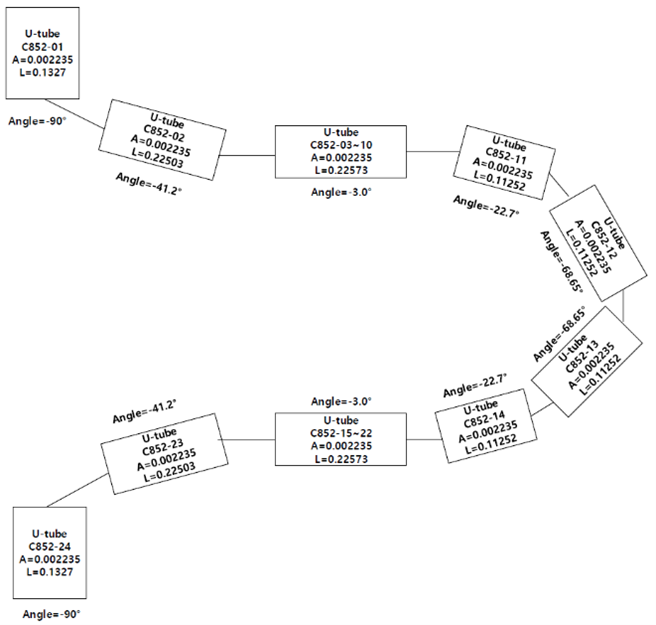

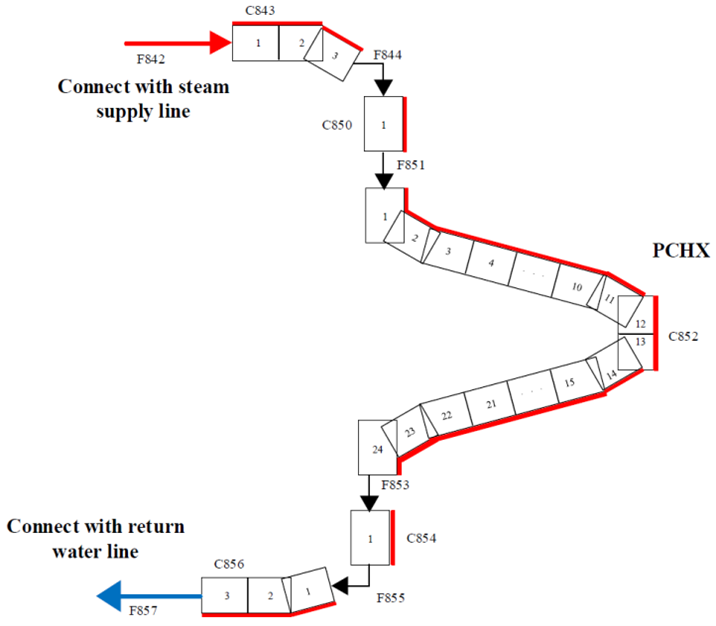

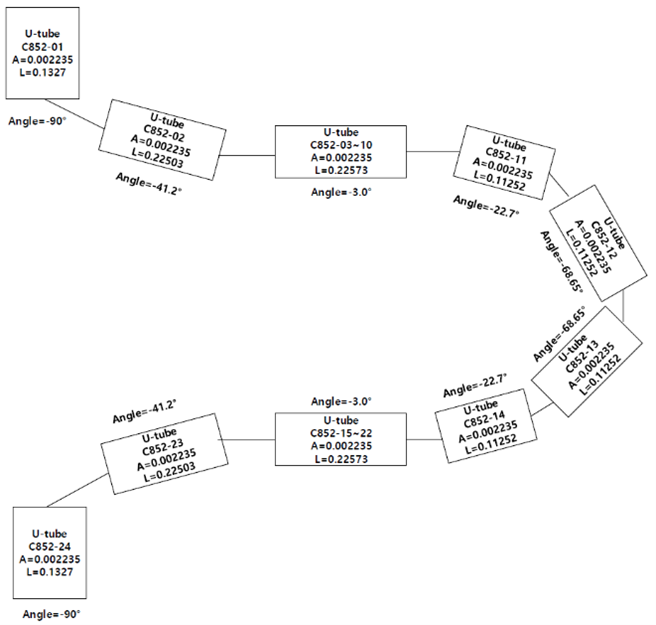

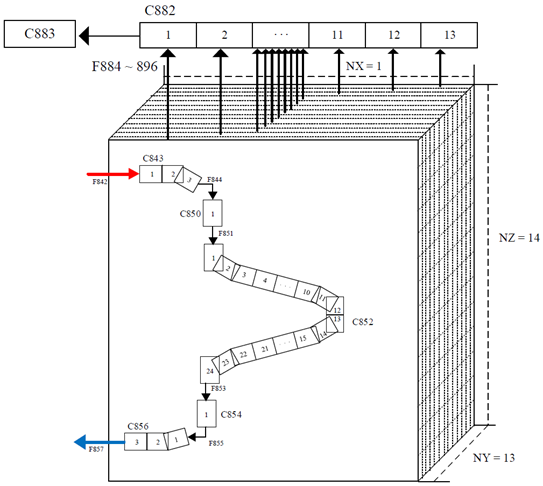

The steam supply and return water line connected the PCHX to the SG-2 of the ATLAS [12]. Therefore, as shown in Fig. 2, the PAFS was modeled by adding junctions at the main steam line and at the economizer nozzle as the inlet and outlet of the PAFS, respectively. The steam supply line and the return water line were divided into 24 nodes and 31 nodes, respectively. The diameters of the steam supply line and the return water line were about 0.04 m and 0.03 m, respectively. The PAFS operation valve was connected to the return water line and the feed water line, and it was modeled as a trip valve. This valve open signal was synchronized to the instant that the collapsed water level in the steam generator reached the set point of the low steam generator level. Once the valve was open, the latched option made it impossible for the valve to close again. The end of the return line was connected to the bottom nozzle of the steam generator economizer volume. The PCHX was the most important component of PAFS, and it was filled with condensate water and the return water line on steady state condition. The condensation tube of PCHX was modeled with 24 nodes as shown in Fig. 3. The length of the horizontal nodes was about 0.23 m and the horizontal part of the PCHX was modeled as 1.806 m. An inclination of 3° was applied to the horizontal tube region while an inclination of 41.2° was applied to one inlet node and one outlet node to simulate a U-shaped bend. These design values were determined to prevent the condensation-induced water hammer inside the tube of PCHX [13]. The area of the PCHX pipe component was about 22.35 cm2, which equals the summation of the three-tube area. The connected heat structures were modeled as a cylindrical shape. The inner and outer coordinates were the inner and outer radii of the tube, respectively. The number of tubes was used as an input for equivalent heat transferring area. The top and bottom headers of PCHX, which both play roles in preventing the vibration of the PCHX tube in the PCCT, were modeled as cell components. The Passive Condensate Cooling Tank (PCCT) of PAFS was designed as a rectangular pool. When the PAFS was actuated, the heat transfer from the PCHX caused the pool water in the PCCT to evaporate, after which the steam flowed through the upper pipe on the top. This upper pipe was connected to the upper cells of the PCCT. Finally, the ‘TFBC’ component, which was connected to the upper pipe, played a role in maintaining the atmospheric pressure. The water pool of the PCCT served as a heat sink. The core decay heat was transferred through the condensation of steam inside the tubes. Therefore, the extracted heat increased the temperature of the pool water. It is expected that rigorous boiling occurred at the tube outside the surface, and a strong buoyancy flow was also expected. In order to simulate natural convection by buoyancy flow in the PCCT, the 3D option of SPACE code was applied to model the PCCT facility as illustrated in Fig. 4. This PCCT model was divided into 182 cells, where the y direction and the z direction were respectively divided into 13 and 14 cells. The cooling water was filled up to nine nodes of the z direction, and the upper nodes were in atmosphere condition. The initial cooling water level in PCCT was about 3.8 m while the water temperature was 28.8°C.

Fig. 1. Modeling diagram of ATLAS and SGTR simulation pipe using SPACE code

Fig. 2. Connection nodding diagram of PAFS to ATLAS steam generator

Fig. 3. Nodding diagram of PCHX

Fig. 4. Nodding diagram of PCCT using ‘3D’ option of SPACE code

3. Results and discussions

3.1 Steady-state results

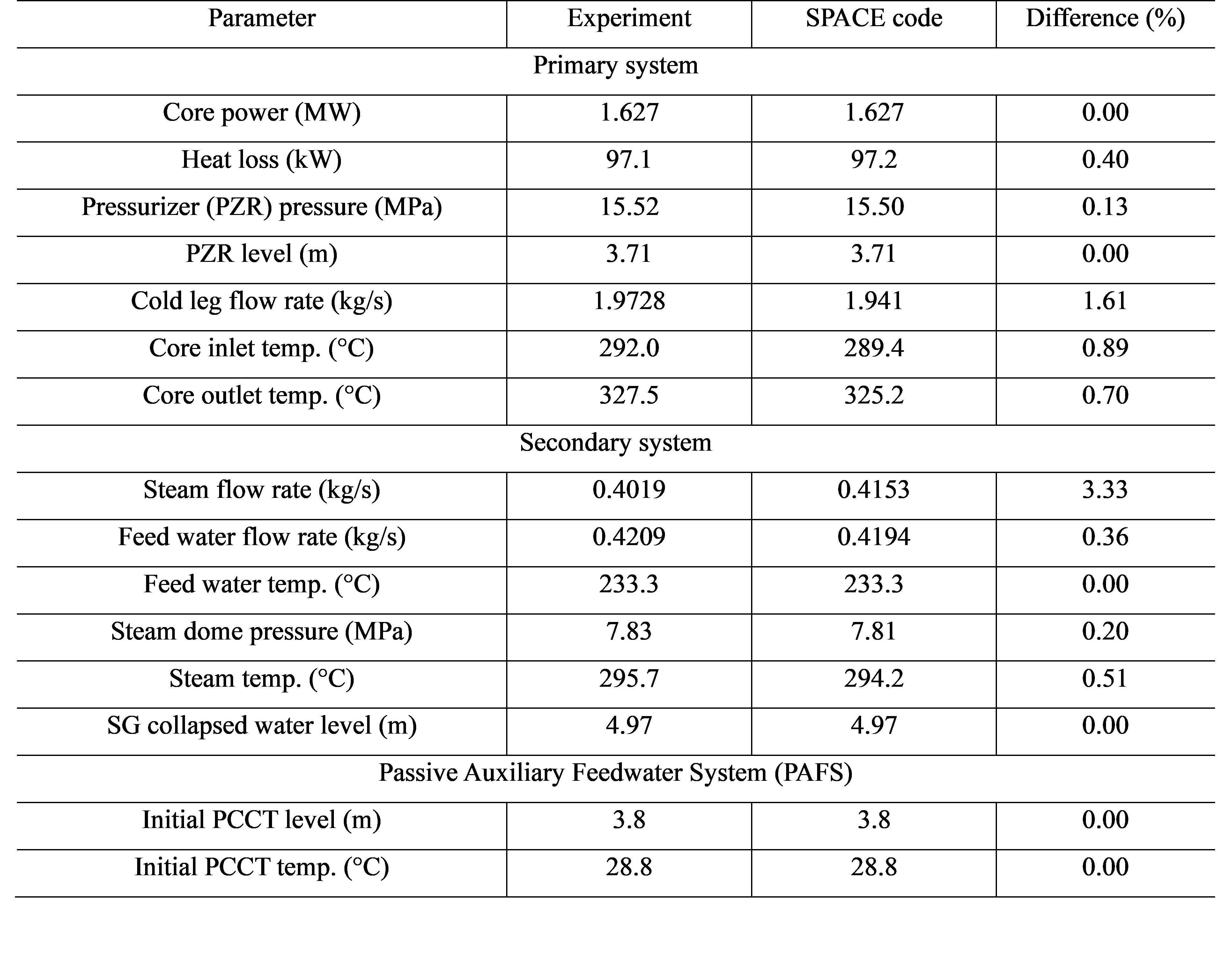

Before using the SPACE model for transient analyses, a consistent set of parameters must be obtained by the steady-state initialization process. Table 1 lists the initial conditions of the experiment, calculated results of the SPACE code, and difference. The initial core power generated by the heater rods was 1.627 MW, and the heat loss of the primary piping into the atmosphere was estimated to be about 97.1 kW based on the information of the initial experiment condition. During the initial conditions, the major thermal hydraulic parameters, including the system pressure, fluid temperature, and mass flow rate, were reasonably consistent with the experiment condition. The calculation time started from -1000.0 s to 0.0 s and all design parameters converged after -500.0 s. After checking the steady state condition, the transient calculation started at 0.0 s of the steady state condition.

Table 1: Comparison results between initial condition of experiment and steady state results of SPACE code

3.2 Transient analysis results

According to the agreement of the ATLAS Domestic Standard Problem-05, the experimental data should be confidential. Therefore, all of the experiment results in this paper including the time frame (t*) were divided by an arbitrary value and plotted on the non-dimensional axis.

3.2.1 Sequence of transient calculation result

Table 2 summarizes the measured and calculated sequences of a MSGTR-PAFS test. The transient was initiated with the MSGTR in normal condition. To initiate the MSGTR transient, the break valve was opened at 0.0 s with the pressurizer heater off according to the experiment scenario. The break flow contributed to the steam generator overfill, and the collapsed water level of the SG-1 reached a set point of HSGL signal, leading to the generation of the HSGL signal. This signal was generated at a later time in the calculation case than it was in the experiment case. The reactor trip occurred simultaneously due to the HSGL signal, and the MSIVs and MFIVs were also closed after their respective delay times. After the MSIVs were closed, the pressure in steam generator was controlled by the cyclic operation of MSSVs. According to the experimental assumptions, the heater power which simulates the decay power had the ANS-73 decay curve applied for the experimental condition, and the heater power started after the reactor trip. For the calculation, time verse decay power data was applied in accordance with the experiment information [4]. The time at which the MSSVs first opened in the experiment and the calculation results were the same after the HSGL signal was triggered. During this steam generator overfill period, the pressure in the primary system decreased substantially. As a result, when the primary system pressure decreased to the set point of the LPP trip, the LPP signal was triggered, and the SIP injection was initiated after the delay time. The collapsed water level of SG-2 decreased due to the decay power, then reached a set point of PAFS operation. Finally, the PAFS operation valve automatically opened and passive cooling using PAFS was initiated.

Table 2: Sequence of transient analysis result

3.2.2 Primary system behaviors

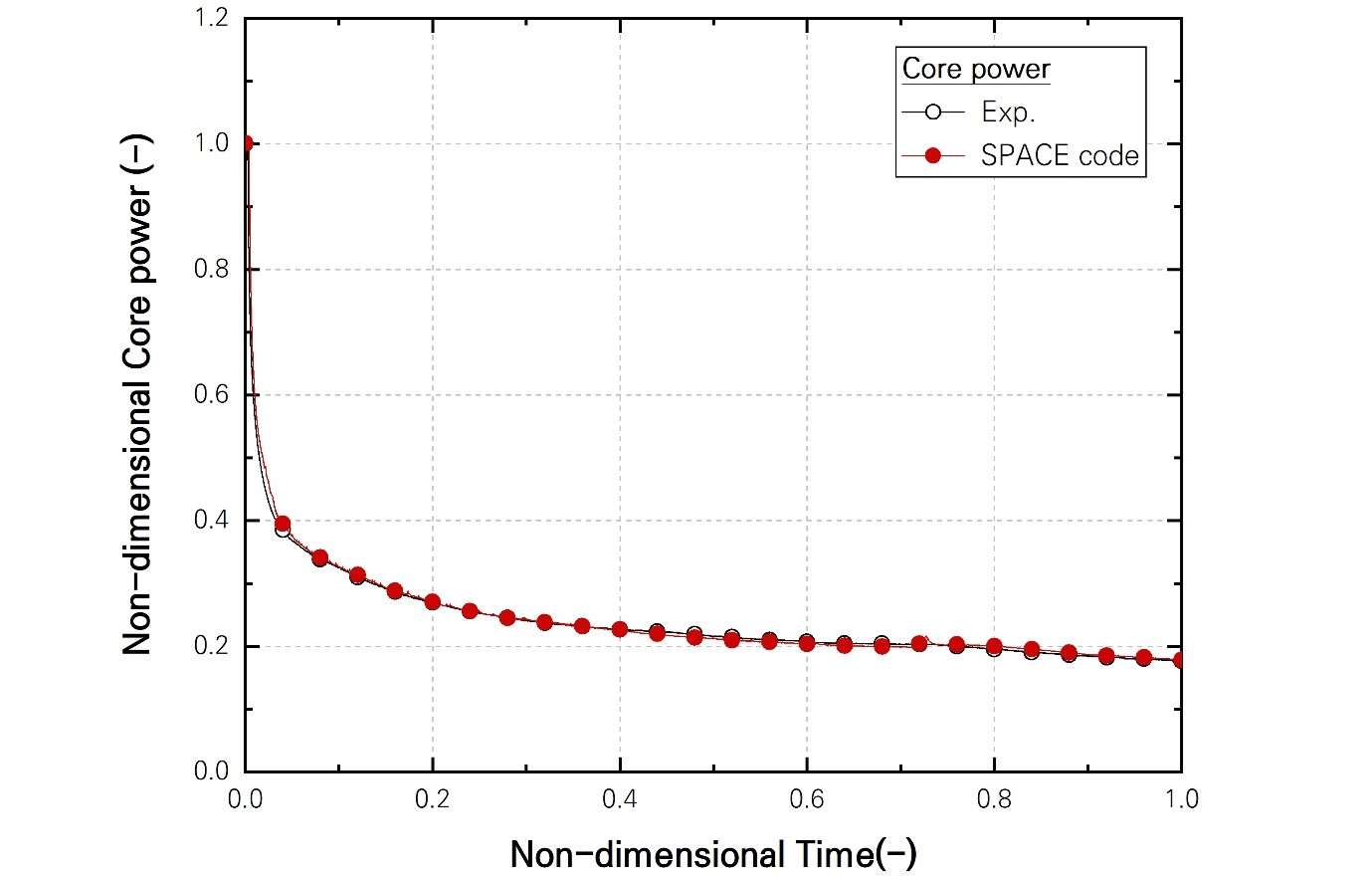

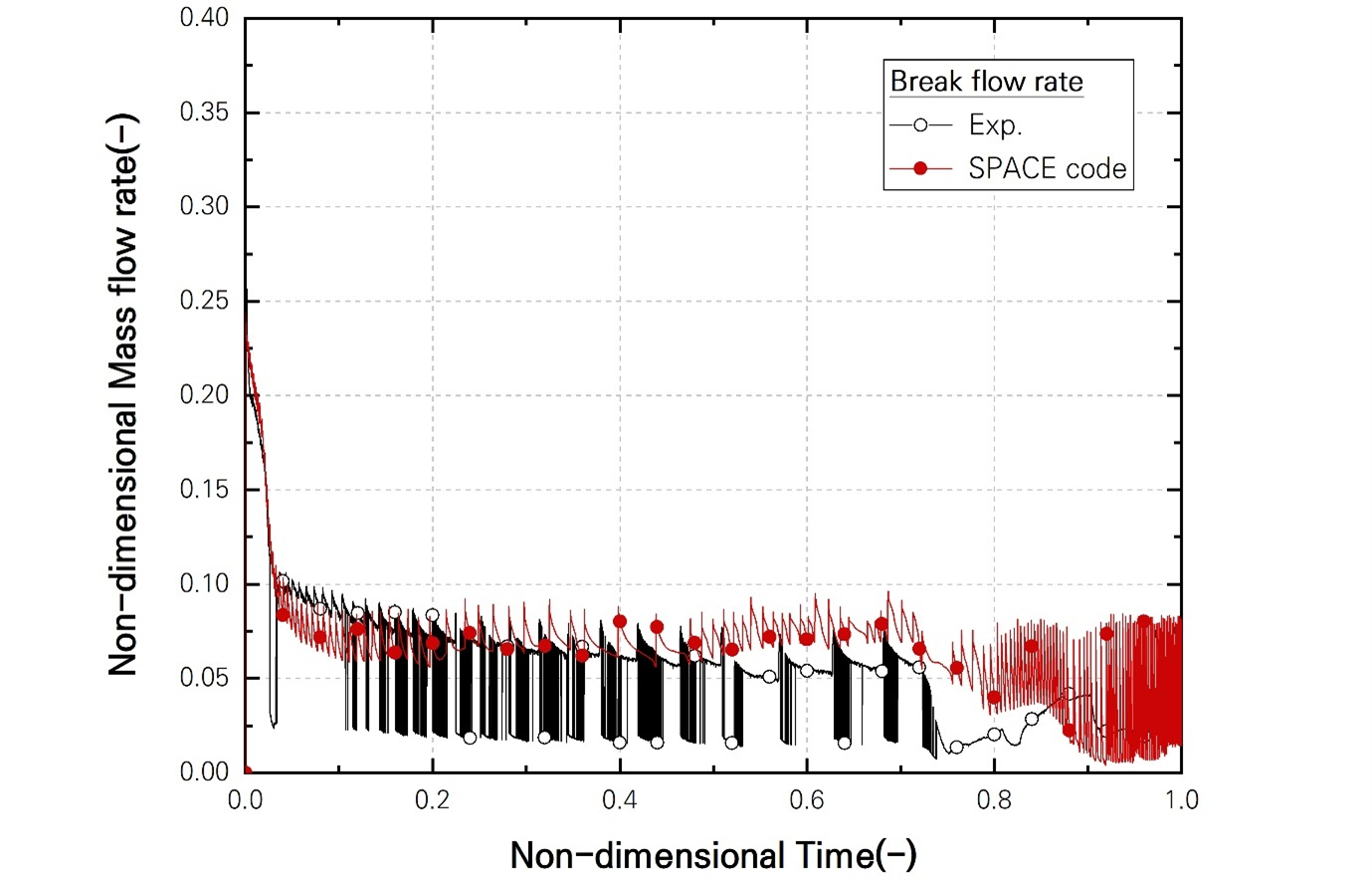

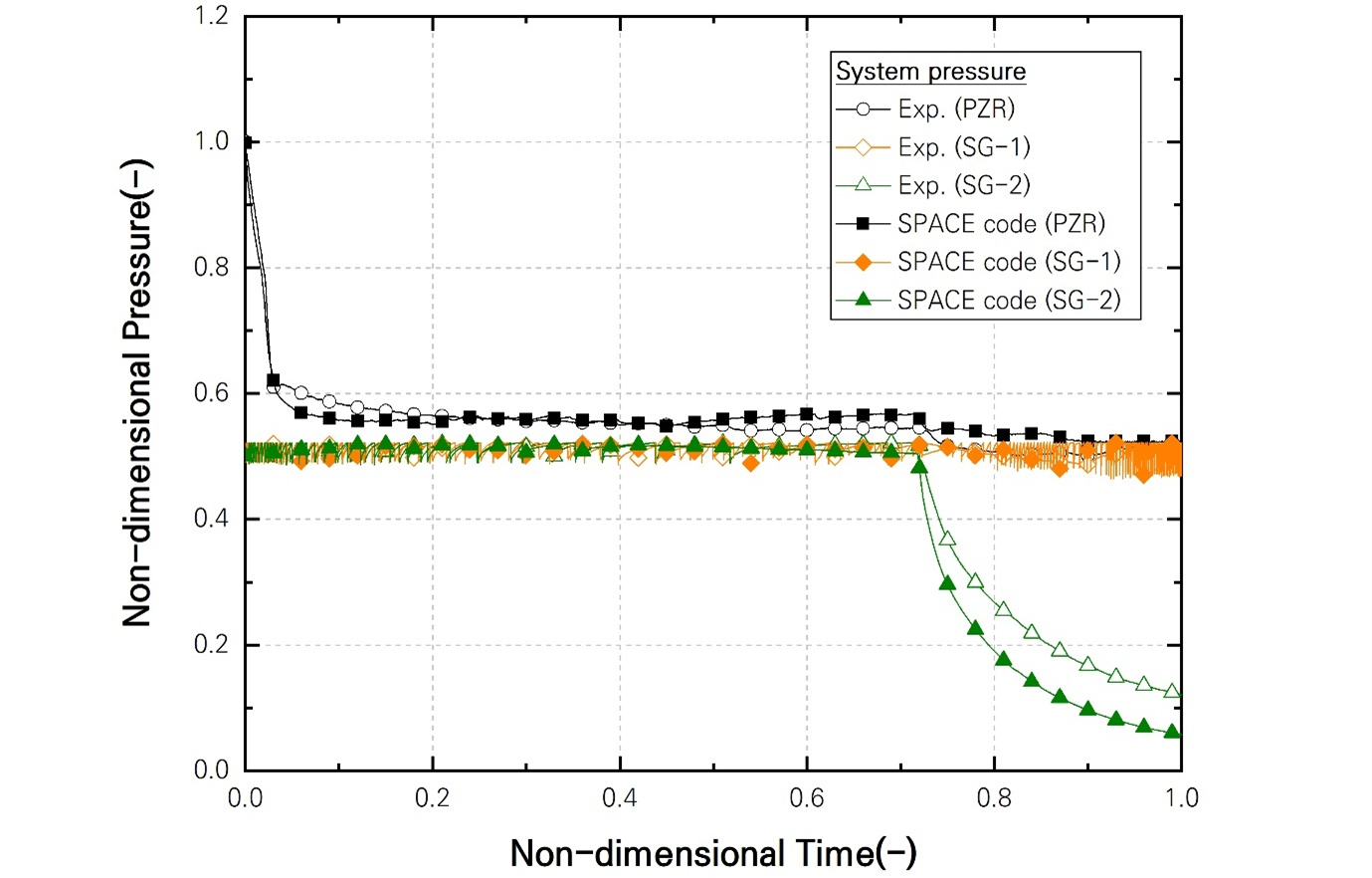

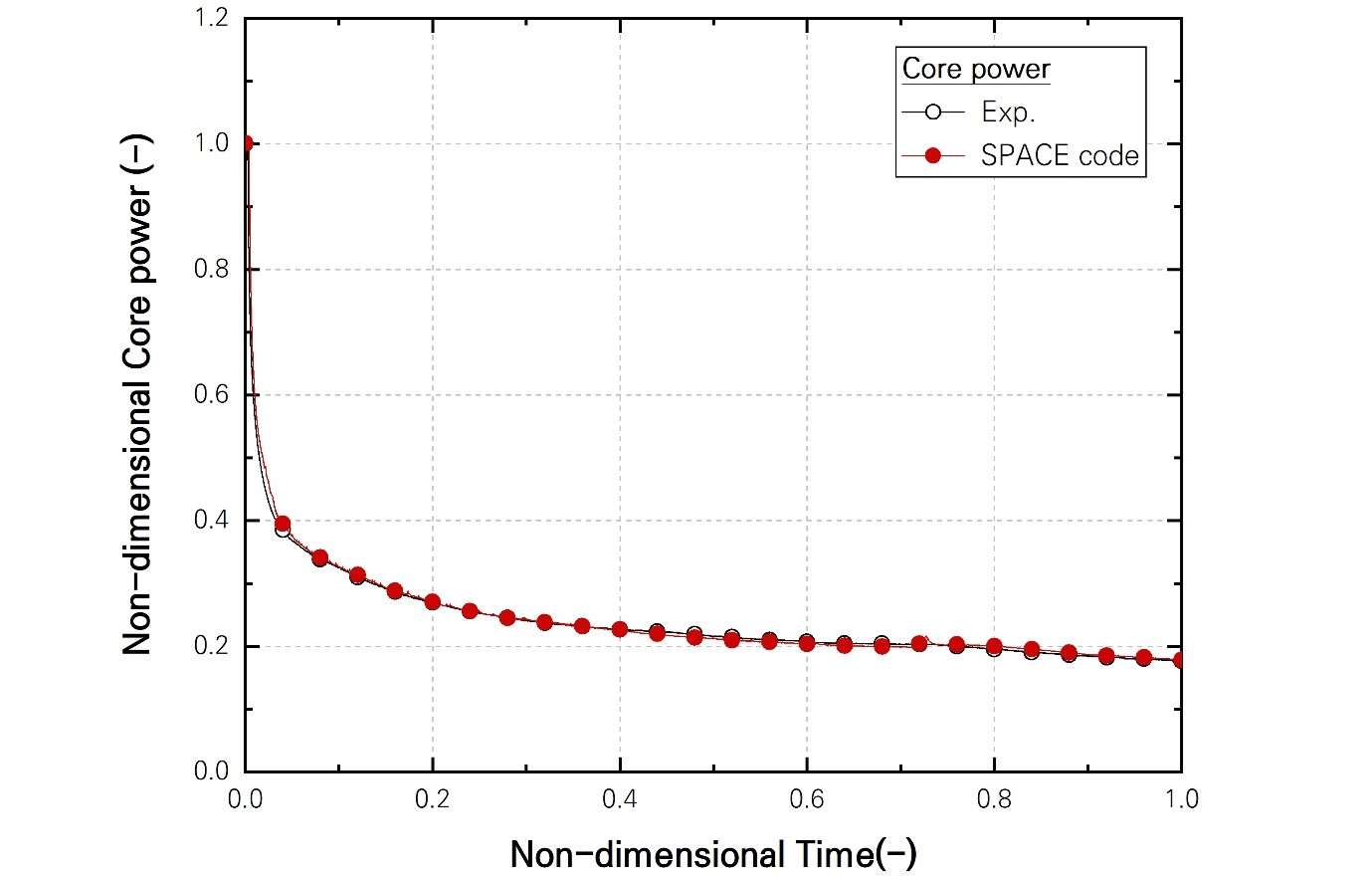

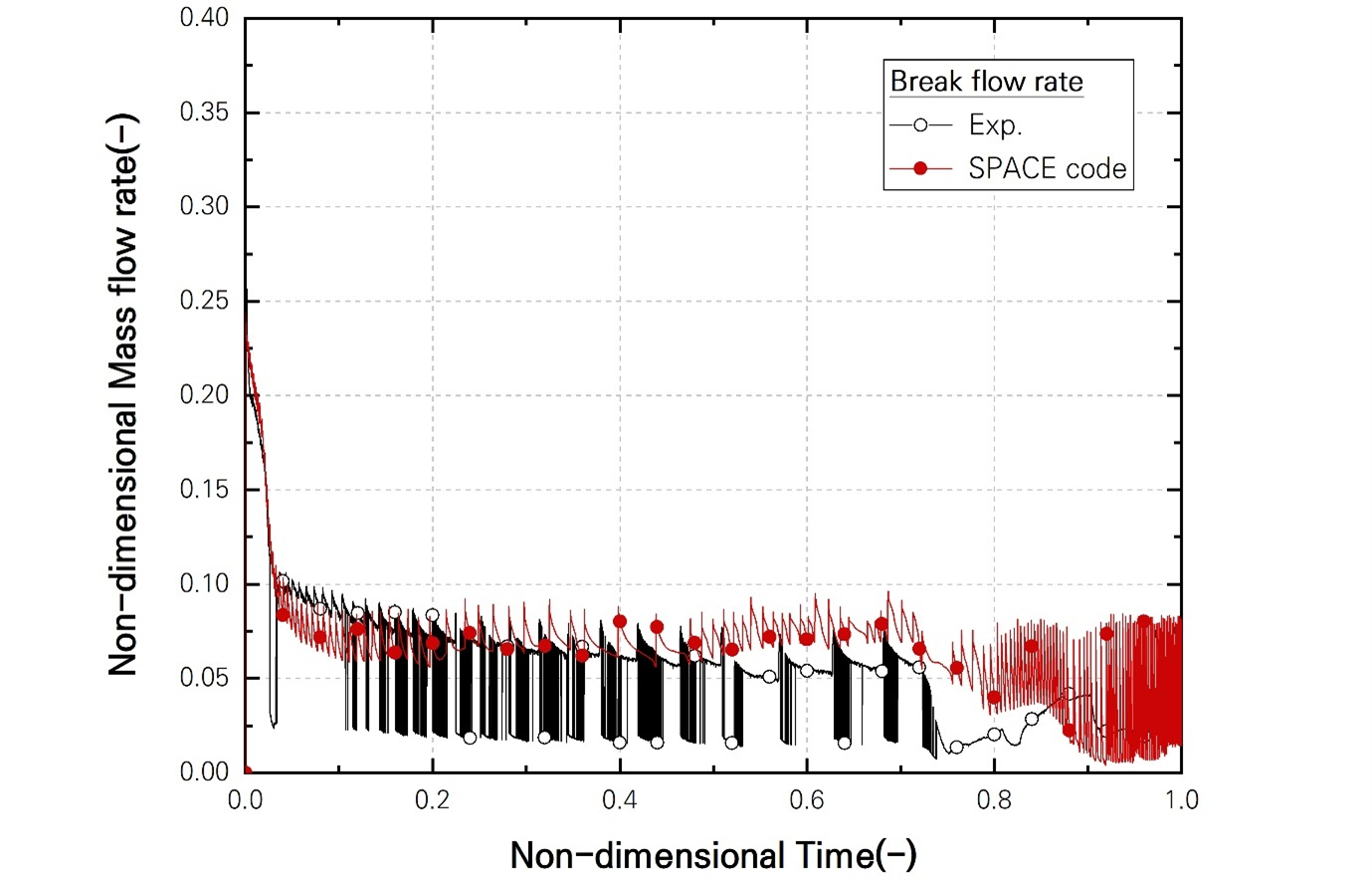

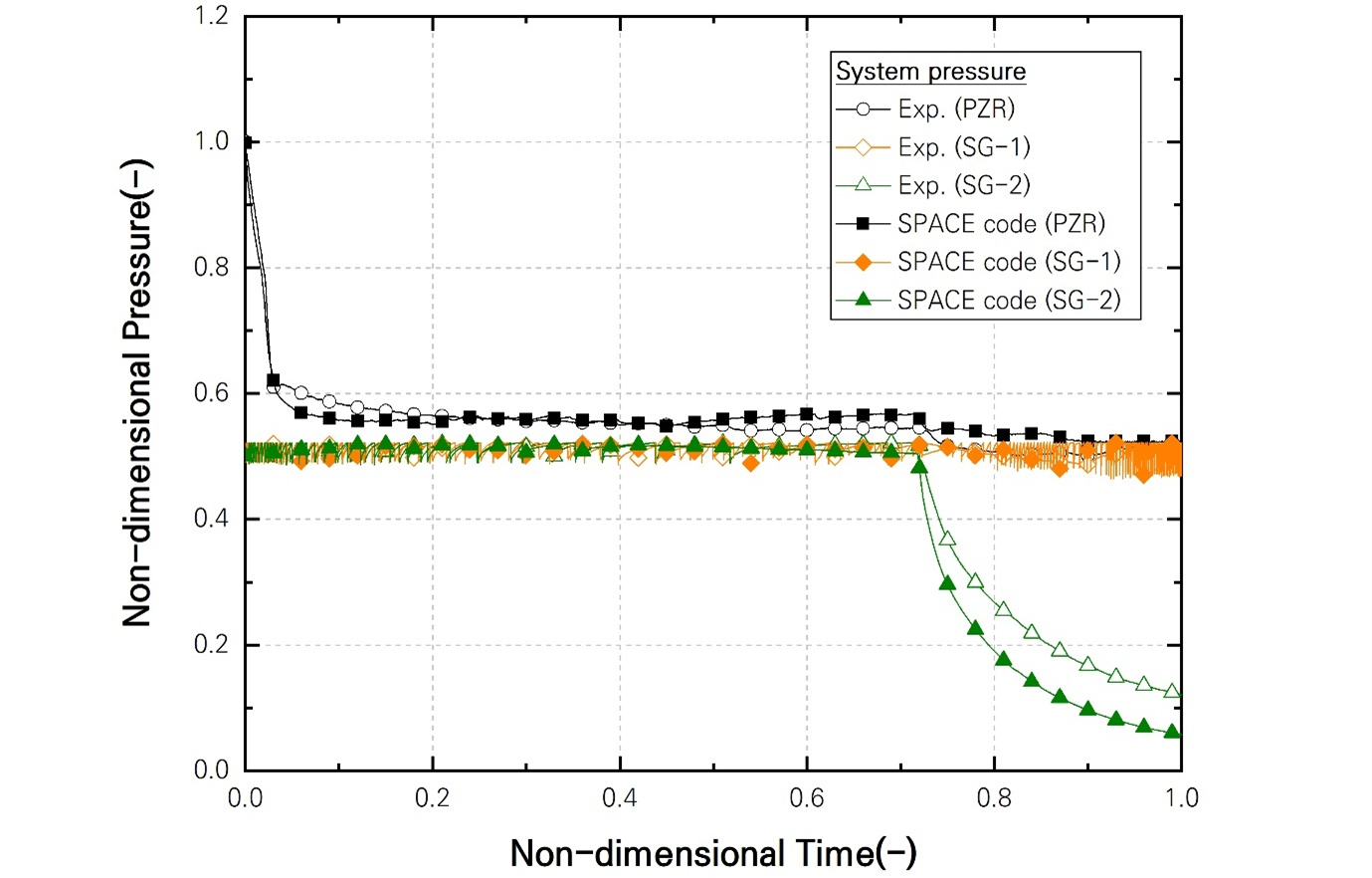

The decay power was one of the important factors in this analysis, and the calculation results were consistent with the experimental result, as shown in Fig. 5. Fig. 6 shows the measured and calculated break flow, which were normalized by the maximum value of the experiment. The break flow rate largely depended on the pressure difference between the primary and the secondary systems. Therefore, as shown in Fig. 6, the peak flow rate occurred at the beginning of transient. After the occurrence of peak flow, the break flow in the experiment case oscillated and gradually decreased. On the other hand, the calculation result shows that the break flow was maintained constantly. The break flow was deeply related to the difference between the pressures of the primary and secondary systems. After the pressure of the primary system was reduced by the break, the pressure of the PZR was predicted to be lower than the experiment results (t* < 0.2 in Fig. 7). The pressure of the primary system was relatively lower than that obtained in the experiment results, thus indicating a lower break flow rate. Due to the lower break flow rate, the pressure of PZR was maintained somewhat higher than the experiment result, which resulted in the break flow rate being maintained (t* > 0.2 in Fig. 7). At the moment the break occurred, the pressure in the pressurizer began to decrease rapidly due to the loss of coolant through the break point. The depressurization rates of the pressurizer obtained from the experiment and the calculation results were almost the same, as shown in Fig. 7. The pressure in the pressurizer continually decreased and reached the set point of the LPP signal.

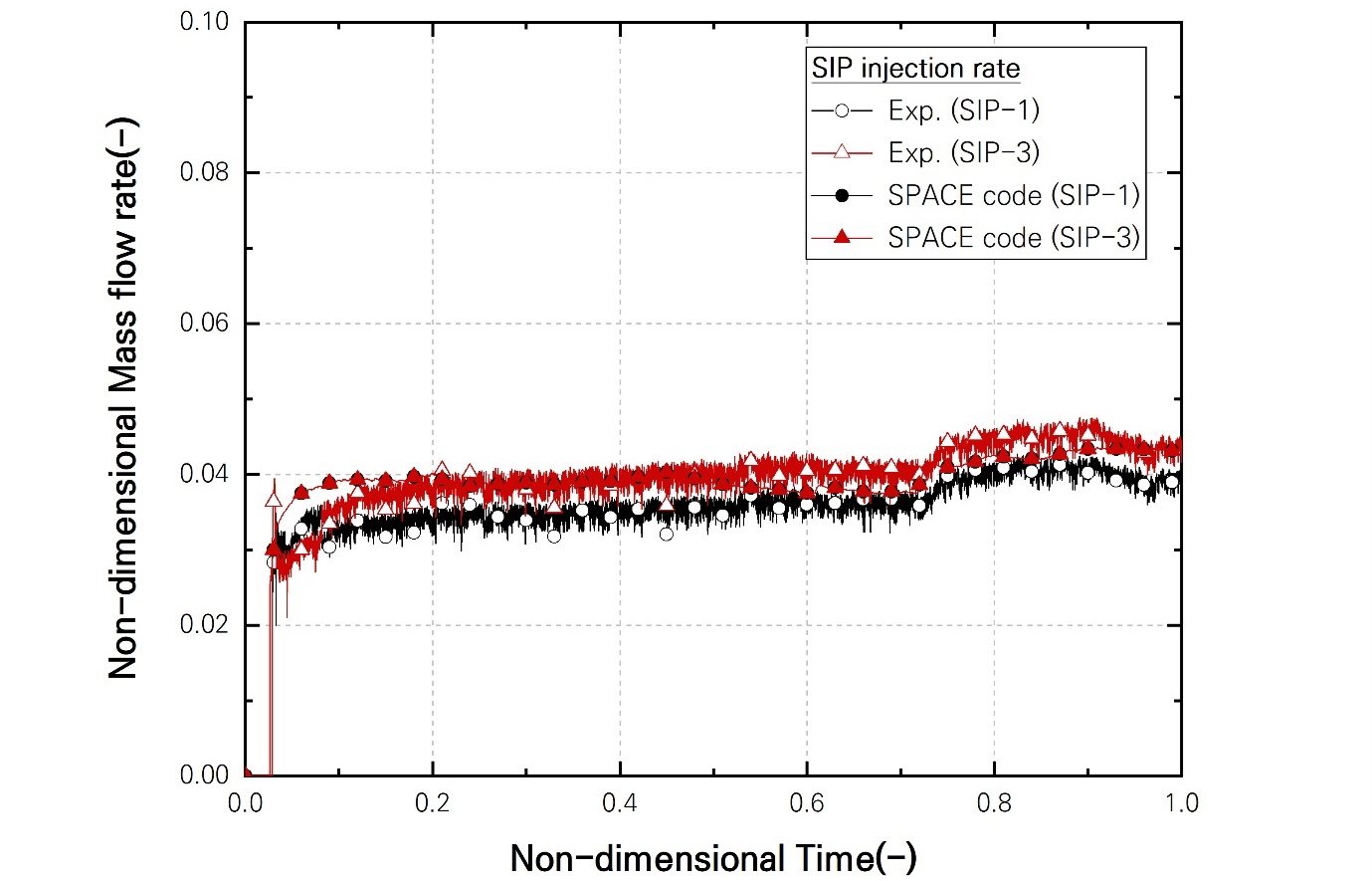

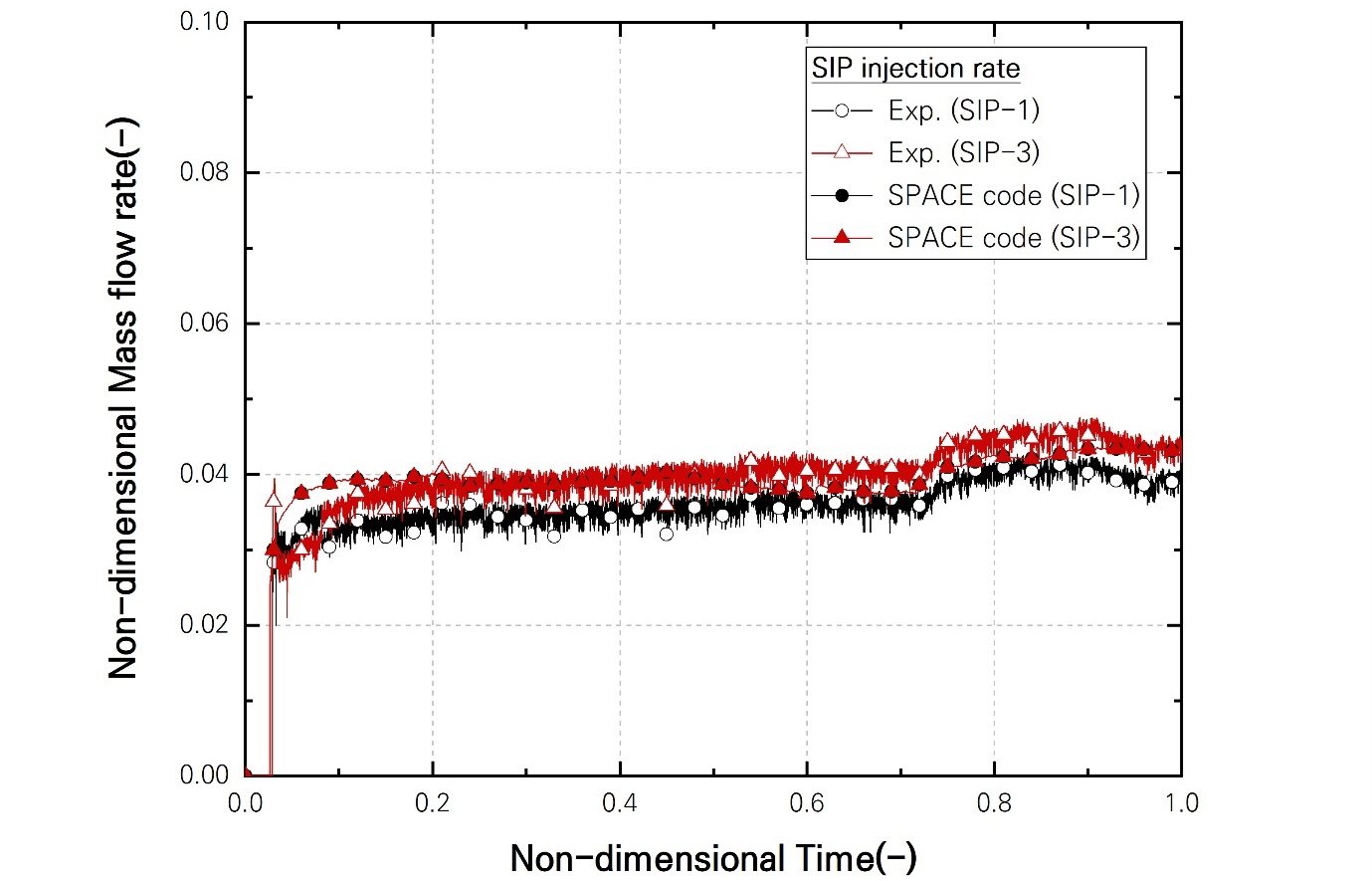

As the LPP signal was generated, the SIP injection was initiated, as shown in Fig. 8. During the beginning phase of SIP injection, the calculation result of the SIP flow rate was slightly higher than the experimental result. This was attributed to that fact that the PZR pressure according to the calculation result remained lower than that obtained in the experiment result. As the accident progressed, the SIP injection rate obtained in the calculation result was consistent with the experiment result. When the RCS pressure reached the saturation pressure due to the decay power, plateau pressure was observed. In addition, the water injected by the SIP contributed to the primary system pressure. Thus, as shown in Fig. 7, the primary system pressure was maintained.

3.2.3 Secondary system behaviors

After the MSIVs were closed by the HSGL signal, the pressure in the steam generator was maintained within the range of the opening and closing set points of the MSSVs. The transient behavior of pressure in the steam generator shows that the calculation result is consistent with the experimental results. Following the PAFS operation, the pressure in an intact SG-2 drastically decreased due to the cooling by PAFS; the SG-2 depressurization trend is similar to the core cooling rate trend.

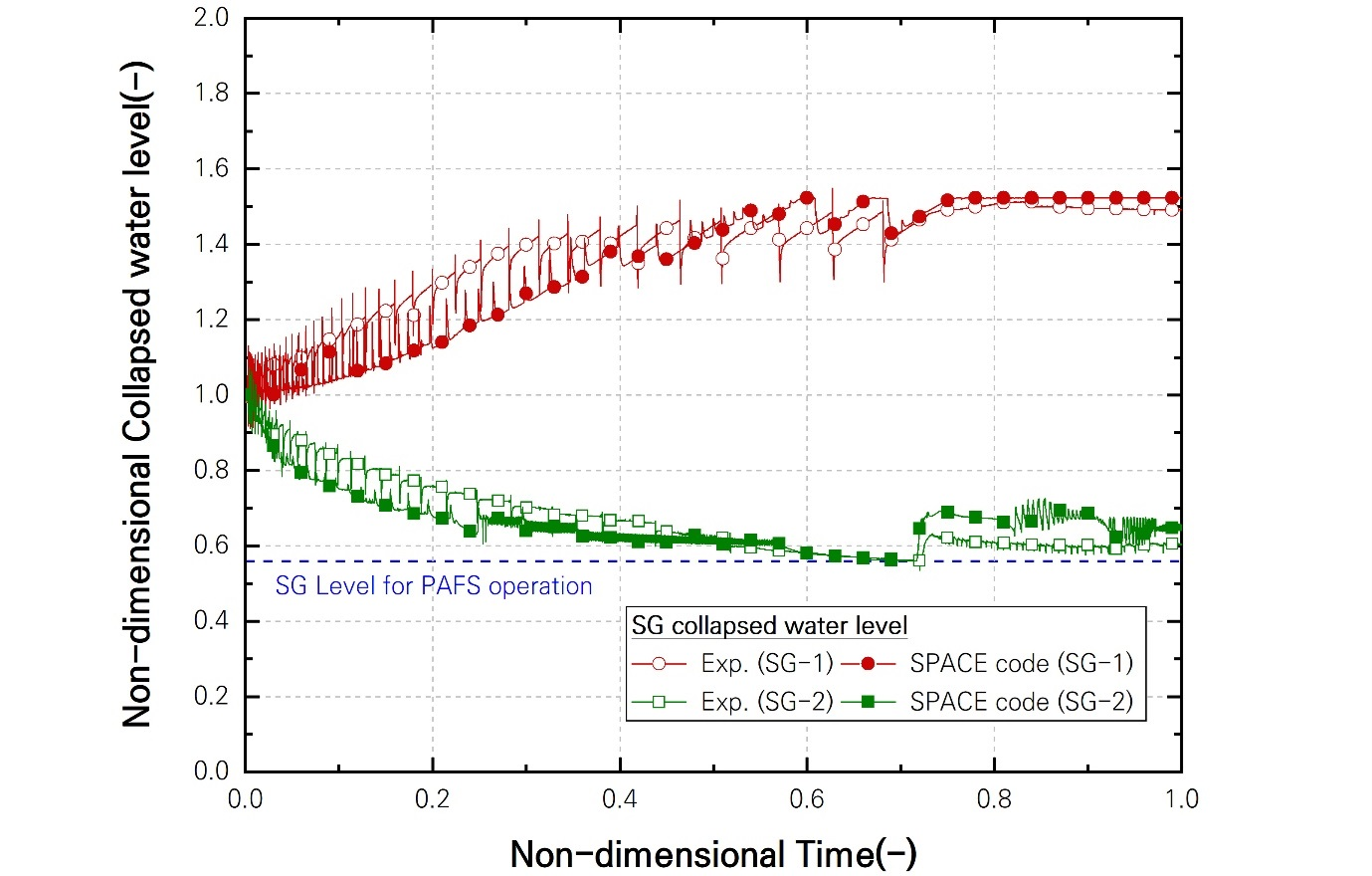

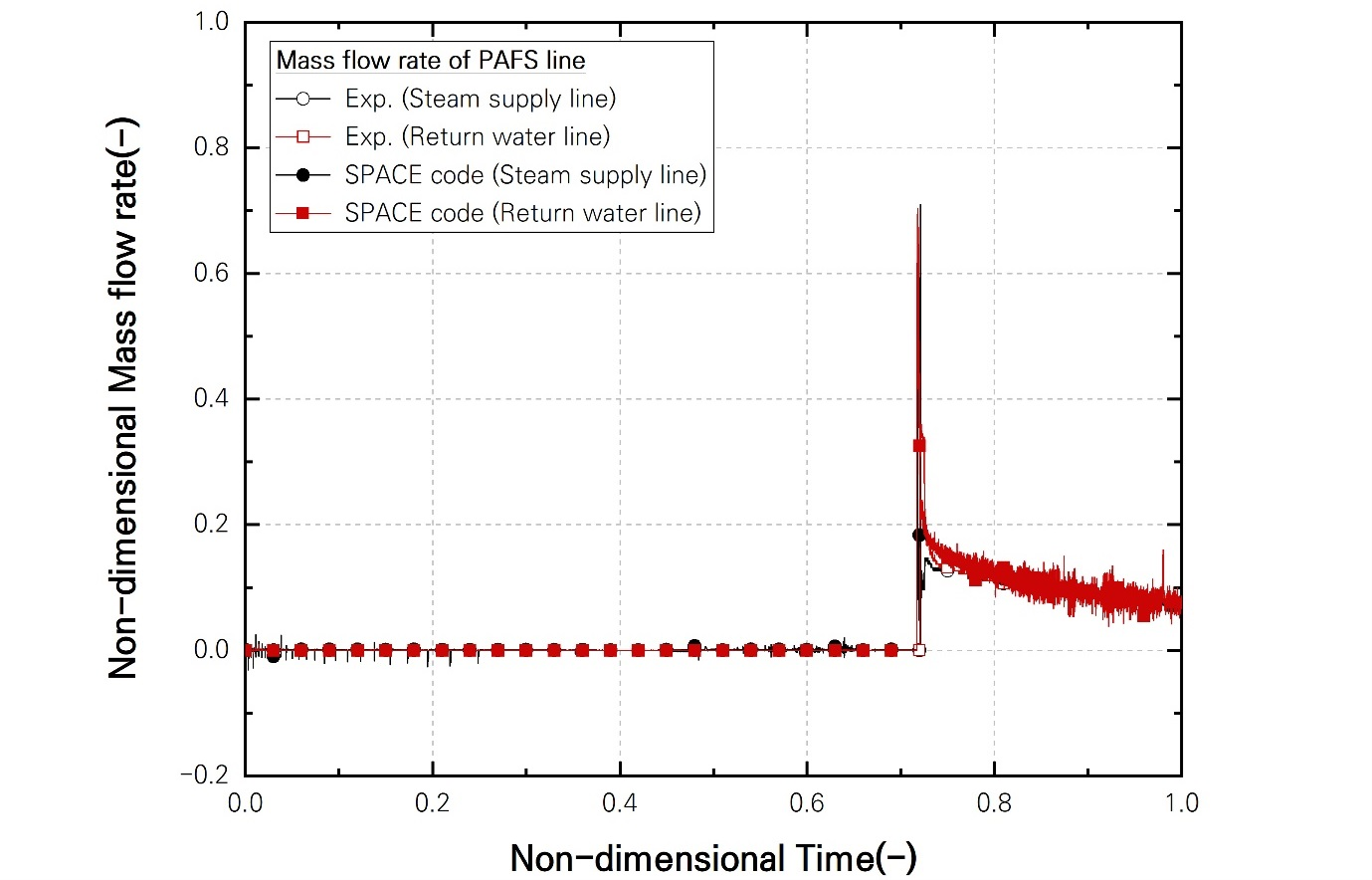

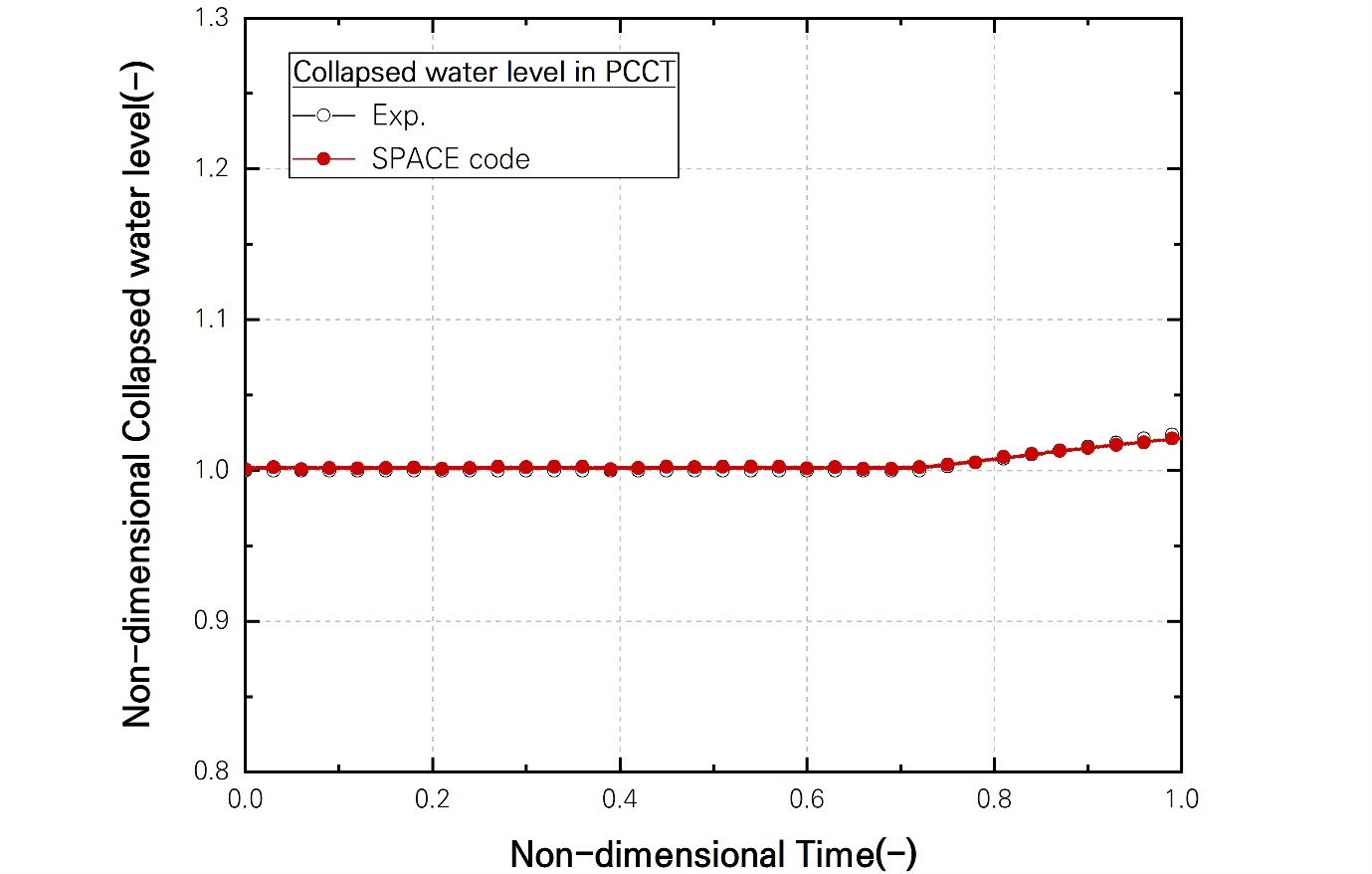

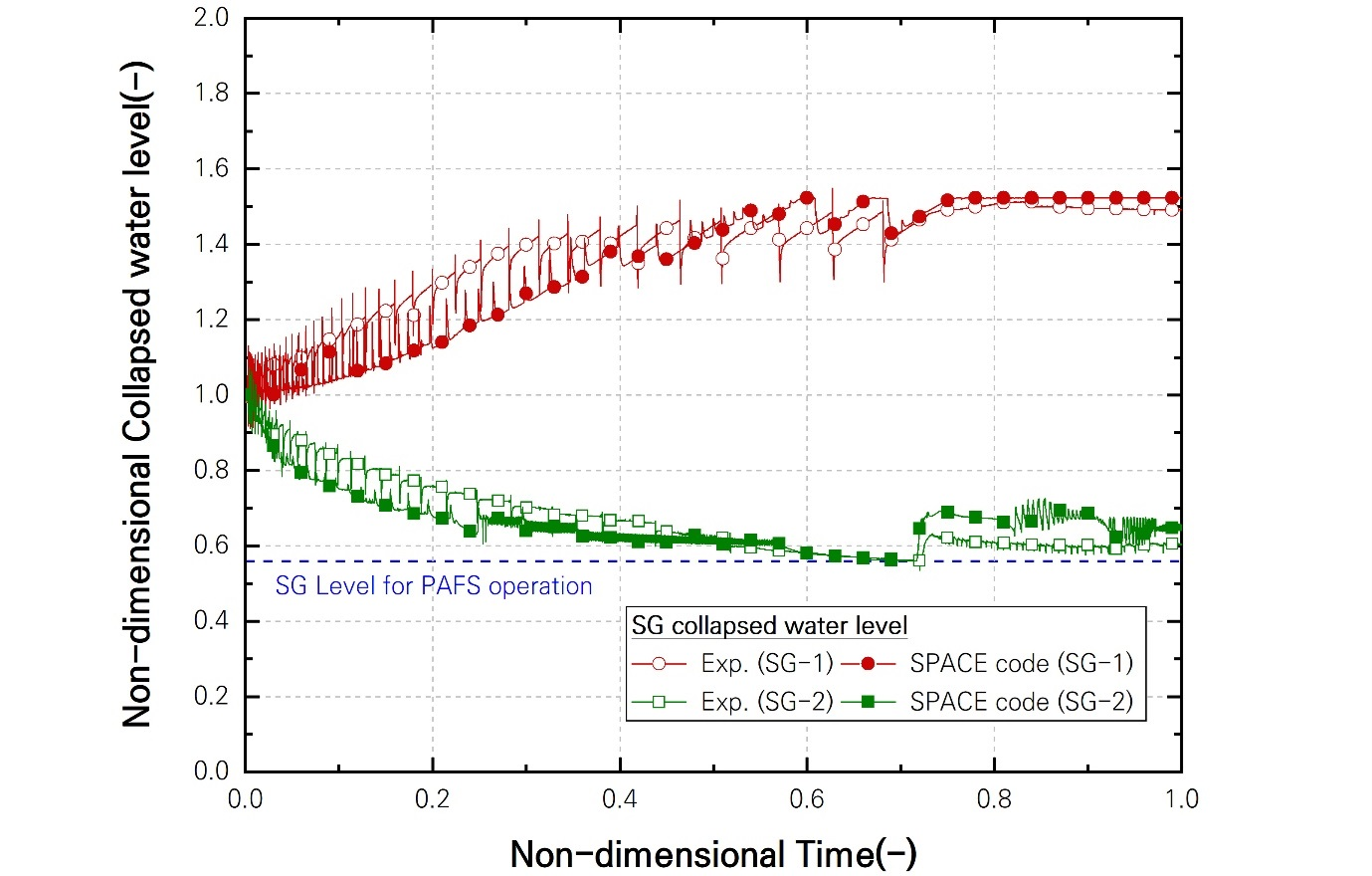

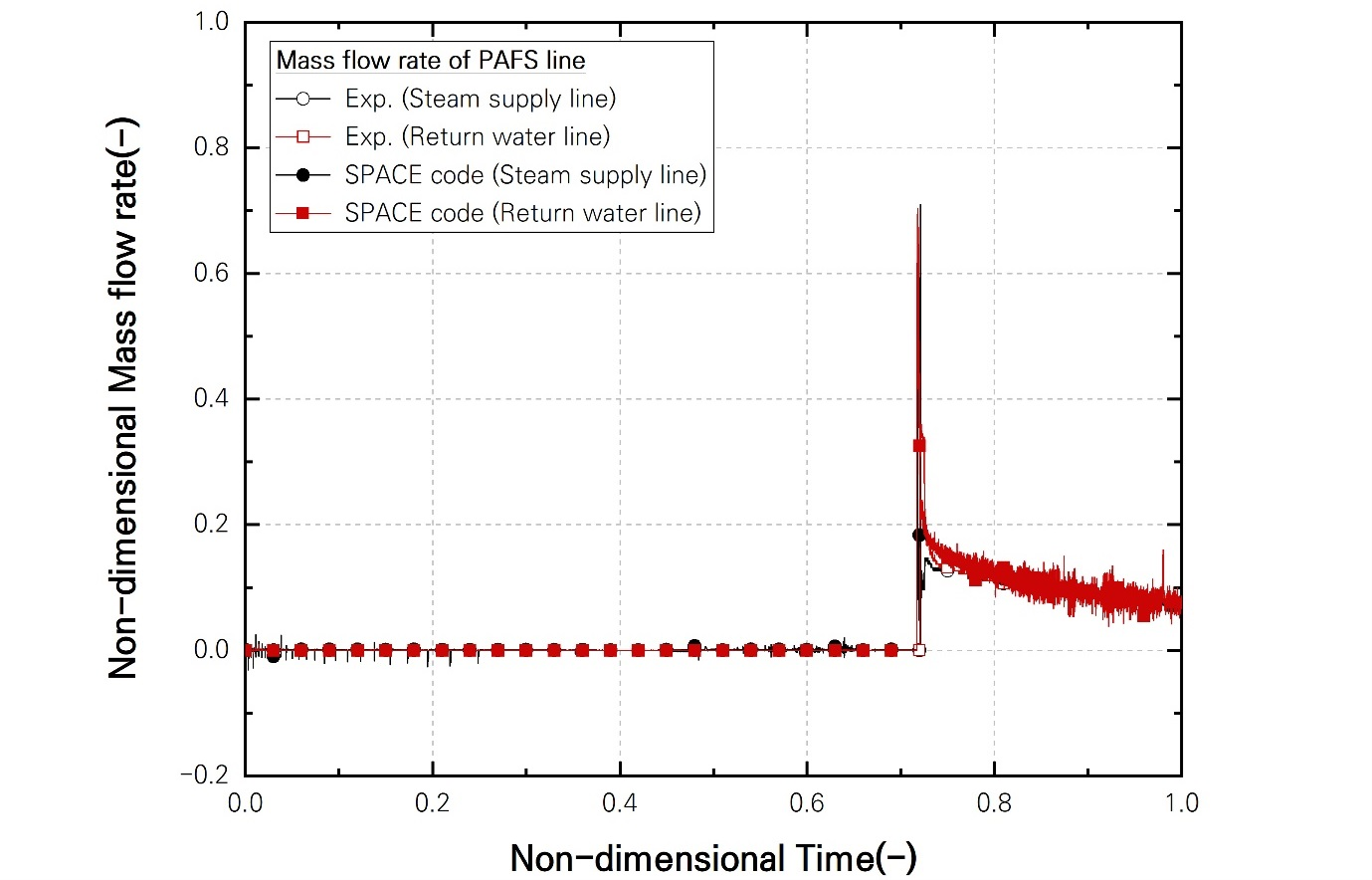

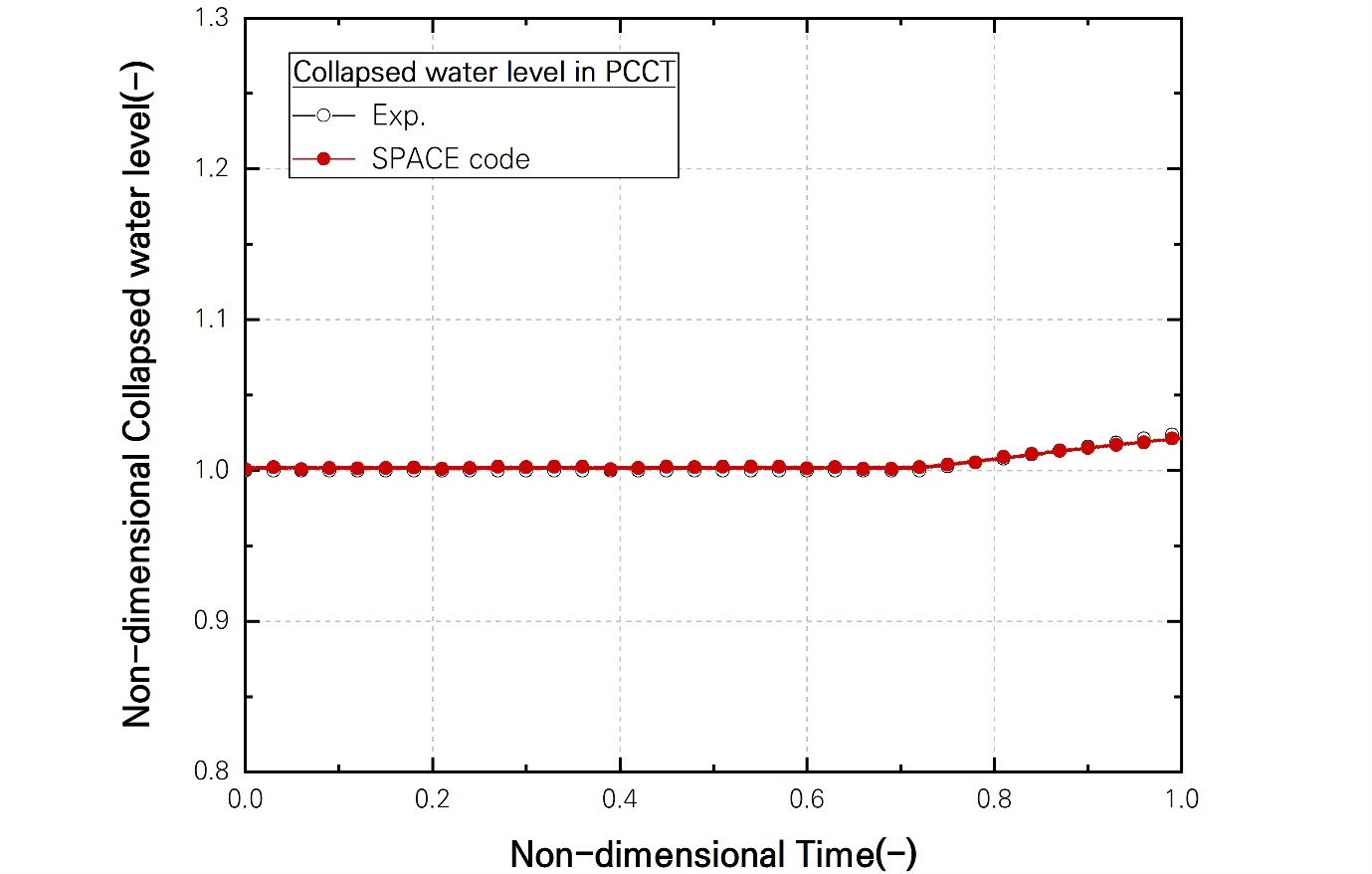

Fig. 9 shows a comparison of the SG collapsed water levels in the experiment and in the SPACE calculation. The water level of broken SG-1 increased and reached the full water level. By contrast, that of an intact SG-2 decreased rapidly and reached a set point of the PAFS operation. As the PAFS signal was triggered, the PAFS operation valve automatically opened, and the main steam from the SG-2 flowed into the steam supply line. As shown in Fig. 10, the mass flow peaked, and then natural circulation flow was formed. The mass flow rate in the case of SPACE calculation was consistent with the experimental result. The main steam from the steam supply line flowed into the condensation tubes, and the condensate circulated through the return water line to the economizer of the steam generator. After the PAFS was actuated, the water level also increased due to the thermal expansion, as shown in Fig. 11.

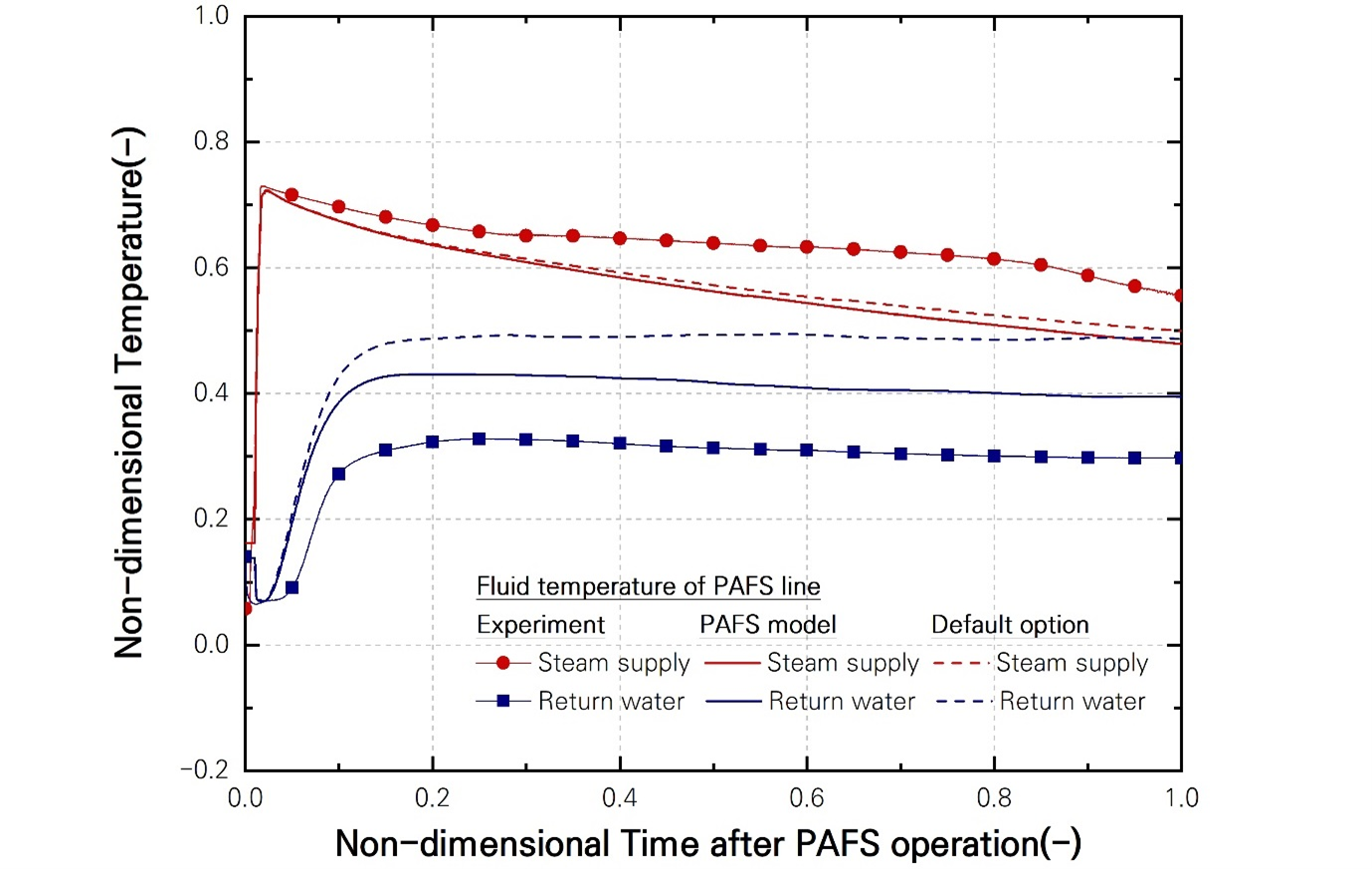

3.2.4 Wall condensation heat transfer model for PCHX

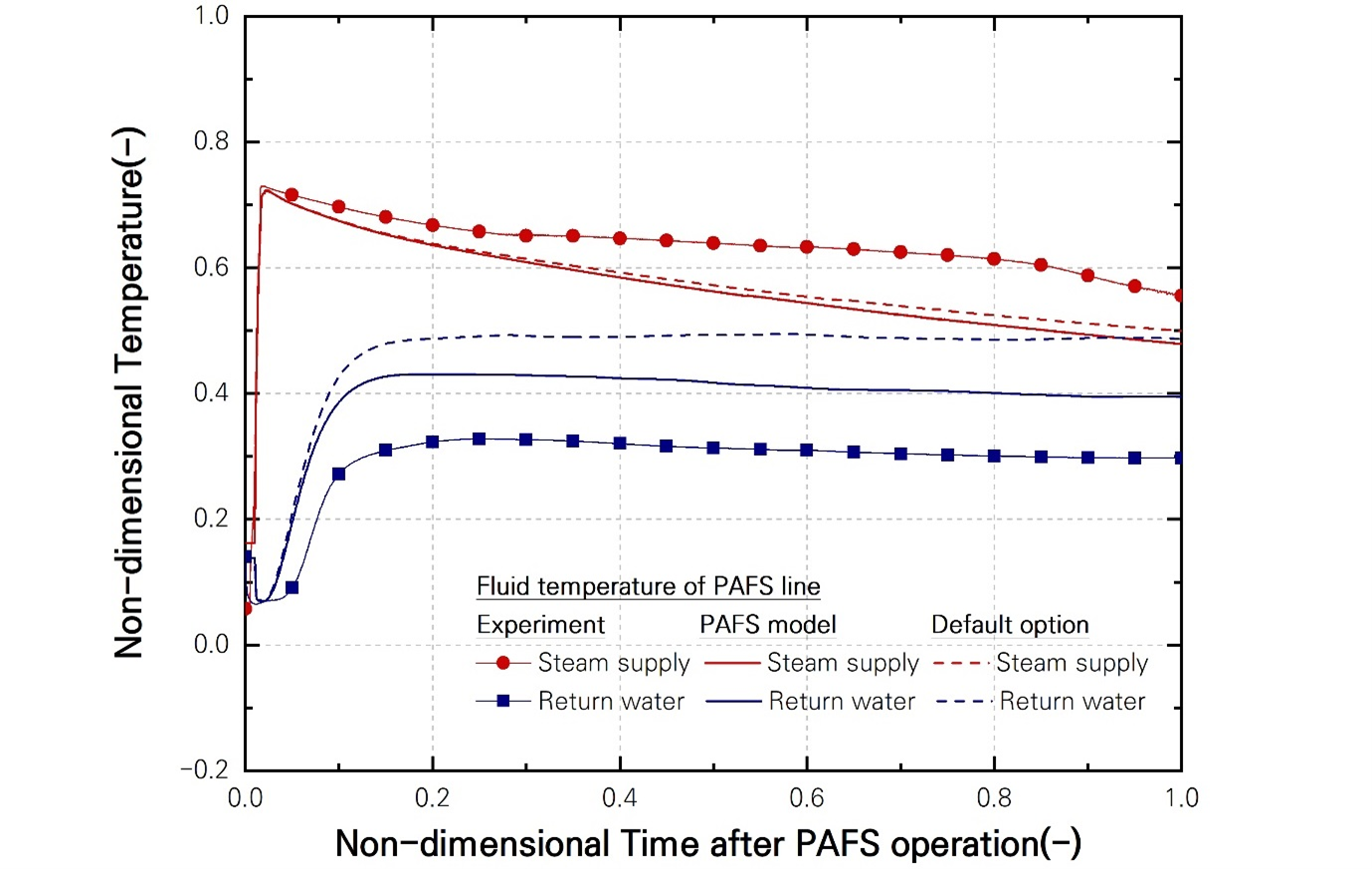

The wall condensation heat transfer rate in PCHX is one of the dominant factors for determining the PAFS cooling capability. Therefore, the many precedent studies related to condensation in PCHX were performed. The wall condensation models were incorporated into the SPACE code heat transfer package. For pure steam condensation, like the problem addressed in this paper, the same model used in RELAP5/MOD3.3 was selected as a default model. The maximum value among Nusselt’s [14], Shah’s [15], and Chato’s [16] correlations is used to consider the geometric and turbulent effects. The experimental correlation for PAFS is also included in the wall condensation model as an option in SPACE code [17]. Based on the calculation results mentioned in chapter 3.2.1, this model was applied. In this section, the default model and experiment correlation model for PAFS were compared to confirm the prediction ability of SPACE code for PCHX cooling performance. Chen’s model, which is the default option in SPACE code, is applied to the outside of PCHX [18].

The fluid temperature after PAFS operation is shown in Fig. 12. The calculation result shows that the fluid temperature on the return water line is higher than the experiment, and that the default option case is highest. That means that the calculation results which were obtained using the default option and the PAFS model underestimated cooling performance. However, the calculation using the PAFS model was more accurate than the default option.

Fig. 5. Comparison result of core power

Fig. 6. Comparison result of MSGTR break flow rate

Fig. 7. Comparison result of system pressure

Fig. 8. Comparison result of SIP injection rate

Fig. 9. Comparison result of SG collapsed water level

Fig. 10. Comparison result of PAFS line mass flow rate

Fig. 11. Comparison result of PCCT water level

Fig. 12. Comparison result of fluid temperature at PAFS line after PAFS operation

4. Conclusions

In this study, a MSGTR experiment with the PAFS operation performed by KAERI was simulated using the SPACE code. This study focused on verifying the prediction capability of the SPACE code for MSGTR accidents, which is one of the multiple failure accidents, and to evaluate the cooling capacity of the PAFS during such an accident. The calculation results showed that the overall system transient results using the SPACE code showed comparatively similar trends with the experimental results in terms of the system pressure, mass flow rate, and collapsed water level in components. Therefore, it was concluded that the SPACE code reasonably predicted the experiment. And, the default model, which uses the maximum value among Nusselt’s, Shah’s, and Chato’s and the experiment correlation model for PAFS in SPACE code were compared to confirm the prediction ability of SPACE code for PCHX cooling performance. The calculation result using the PAFS model was more accurately estimated than the default option.

Based on the present calculation results, the following conclusions were obtained in this study. First, the experiment and calculation results showed that the cooling capability of PAFS is sufficient to replace the active auxiliary feedwater system during MSGTR transient. Additionally, it is recommended that the PAFS model in SPACE code be applied for more accurate prediction results for PAFS operation by performing a safety analysis of an APR+ nuclear power plant.

Acronyms and Abbreviations

Acknowledgements

This work was performed within the program of the fifth ATLAS Domestic Standard Problem (DSP-05), which was organized by the Korea Atomic Energy Research Institute (KAERI) in collaboration with the Korea Institute of Nuclear Safety (KINS) under the national nuclear R&D program funded by the Ministry of Education (MOE) of the Korean government. The authors are also grateful to the fifth ATLAS DSP-05 program participants: KAERI for the experimental data and to the council of the fifth DSP-05 program for providing the opportunity to publish the results.

References

[1] Korean NSSC, Regulations on the Scope of Accident Management and the detailed criteria of Accident Management Capability Evaluation, Notification No. 2017-34 of the Nuclear Safety and Security Commission in Korea, Rev.1 (2017).

[2] IAEA, Safety of Nuclear Power Plants: Design, IAEA Specific Safety Requirements No. SSR-2/1, Rev.1 (2016).

[3]J.H. Koh et al., Current status of design extension conditions technology development for prevention of severe accident in nuclear power plants, 13th International Conference on probabilistic Safety Assessment and Management (PSAM 13) (2016).

[4] KAERI, Experimental Study on the Multiple Steam Generator Tube Rupture with Passive Auxiliary Feedwater System Operation, KAERI/TR-8010/2020 (2020).

[5] J. Cheon et al., The Development of a Passive Auxiliary Feedwater System in APR+, ICAPP2010, San Diego, USA (2010).

[6] S.J. Ha et al., Development of the SPACE code for nuclear power plants, Nuclear Engineering and Technology 43, (2011) 45-62.

[7] IAEA, Safety Assessment for Facilities and Activities, IAEA Safety Standards Series No. GSR Part 4, Rev.1 (2016).

[8] Petruzzi, A., D’Auria, F., Thermal-Hydraulic System Codes in Nuclear Reactor Safety and Qualification Procedures, Science and Technology of Nuclear Installations, Vol. 2008, Article ID 460795, (2008) p.16.

[9] KAERI, Description report of ATLAS facility and instrumentation, KAERI/TR-7218/2018 (2018).

[10] Y.S. Kim et al., Commissioning of the ATLAS thermal-hydraulic integral test facility, Annals of Nuclear Energy, Vol. 35, (2008) pp. 1791-1799.

[11] K.H. Kang et al., Separate and integral effect tests for validation of cooling and operational performance of the APR+ Passive Auxiliary Feedwater System, Nuclear Engineering and Technology 44, No.6, (2012).

[12] KAERI, Description report of ATLAS-PAFS Facility and Instrumentation, KAERI/TR-5545/2014 (2014).

[13] B.U. Bae et al., Design of condensation heat exchanger for the PAFS(Passive Auxiliary Feedwater System) of APR+ (Advanced Power Reactor Plus)”, Annals of Nuclear Energy, Vol.46, (2012) 134-143.

[14] Nusselt, W.A., The surface Condensation of Water Vapor, Zieschrift Ver. Deut. Ing., 60, (1916) p.541.

[15] Shah, M.M., A general correlation for heat transfer during film condensation inside pipes, Int. J. Heat Mass Transfer, 22, (1979) p.547.

[16] Chato, J.C., Laminar Condensation inside Horizontal and Inclined Tubes, American society of heating, refrigeration and air conditioning engineering journal, 4, (1962) p.52.

[17] B.U. Bae et al., Evaluation of mechanistic wall condensation models for horizontal heat exchanger in PAFS (Passive Auxiliary Feedwater System), Annals of Nuclear Energy, Vol.107, (2017) 53-61.

[18] K.Y. Choi et al., Development of a wall-to-fluid heat transfer package for the SPACE code, Nuclear Engineering and Technology, Vol.41, No.9 (2009).

0 Comments