Numan Iqbal1

Rab Nawaz2

Kamran Rasheed Qureshi1

Ammar Ahmed1

R. Khan2,3

–

International Trends & Developments in Nuclear

1 Department of Mechanical Engineering, Pakistan Institute of Engineering and Applied Sciences (PIEAS).

2 Department of Nuclear Engineering, Pakistan Institute of Engineering and Applied Sciences (PIEAS).

rustam_pieas@yahoo.com

Article

–

–

–

–

CFD Simulations of Single Phase Pressurized Thermal Shock in the RPV of a 330MWe PWR

This research presents the computational fluid dynamics (CFD) simulation of pressurized thermal shock (PTS) in the reactor pressure vessel (RPV) of a nuclear power plant (NPP) using ANSYS FLUENT. PTS challenges the integrity of the RPV structure, which causes a disturbance in the estimation of plant life. The highly critical situation takes place during the cold-water introduction in the cold legs after a proposed loss of coolant accident (LOCA). PTS study involves the determination of the probability of overcooling events, thermal-hydraulics study and structural analysis of RPV. In the present work, thermal-hydraulics study and structural analysis of RPV has been conducted. For the validation purpose, RPV model of two-loop Westinghouse type pressurized water reactor (PWR) has been used. This model contains four injection lines of the emergency core cooling system (ECCS). By assuming a proposed medium break LOCA in one of the hot legs of RPV, thermal hydraulics study has been carried out at different flow rates and various thermal conditions. Boundary conditions applied were in the form of mass flow rates at inlet and pressure at the outlet. Results of the thermal-hydraulics study were coupled with pressure and thermal loads of structural analysis for the complete scenario of PTS. Value of stress at different locations of RPV was also obtained. Developed CFD methodology was then applied to RPV of a 330 MWe NPP which is also a two-loop Westinghouse type PWR. Results of temperature distribution were compared with the published results. Thermal hydraulics studies show the three-dimensional conduct of the flow area and temperature distributions in the RPV. Structural analysis results show that the maximum stress region occurs at the exit of the inlet nozzle in the downcomer. The maximum value of stress obtained was less than the design value of RPV material so RPV is safe for this accident.

1 Introduction

The lifespan of an NPP, from development to decommissioning, might be between 50-60 years. It is hoped that in the near future it will have a much longer operational period. During operational years, NPP undergoes different mechanical, chemical and the physical conditions that with time lead to a change in the properties of materials, that could influence the performance of the nuclear systems or, in worst conditions, could get to an absolute loss of the system design function [1]. Subsequently, the aging process is seriously considered from design up to the assembling stage. RPV is clearly the primary character in the estimation of the NPP lifetime, being the main hindrance between radioactive products and the environment. PTS transient can occur when cold water is injected by the emergency core cooling system (ECCS) during a LOCA in the cold leg of RPV. Hot water or steam present in the cold leg mixes with injected water [2]. Cold plumes are formed which flow in the downcomer after entering in the RPV to cool the inner RPV wall. Large temperature gradients are present in the downcomer. These large temperature gradients can produce large thermal stresses on RPV wall and it can cause flaw or in the worst-case scenario rupture it [3].

In the available literature, several experimental and computational studies have been reported regarding the PTS. Experimental test facilities are mostly used to supply data for the validation of CFD models for PTS study. Top-flow PTS test facility, situated in Helmholtz-Zentrum Dresden-Rossendorf (HZDR), which uses a flat downcomer geometry [4]. Scale for test facility geometry is 1:2.5. UPTF (Upper Plenum Test Facility) test geometry is the copy of the primary system of Siemens/KWU 1300 MWe PWR present in Mannheim [5]. ROCOM (Rossendorf Coolant Mixing Model) test facility having a scale of 1:5 is the model of German Konvoi type reactor for the primary system [6].

Along with experimental test facilities, numerical simulations of PTS have been performed by many researchers as well. Apanasevich et al. [7] performed CFD simulations for the validation of CFD models and understanding of PTS. Experiments were performed for air/ water case and steam /water case. To validate the codes simulations were run on three types of codes namely NEPTUNE-CFD, ANSYS –CFX and ANSYS-FLUENT. Results of the experiments were compared by the results of codes and conclusions were drawn. For the experiments, an experimental setup was used at HZDR. It consists of a cold leg, flat downcomer and pump simulator. The pressure was maintained constant at or below 5 MPa. For CFX simulation, a two-fluid methodology was utilized. For FLUENT simulation, the volume of fluid approach was utilized to compute the air/water and steam /water case. Results of CFD simulations were good except for the zone in the locality of ECC jet. However, the contrast in the results of experiments and the various codes was quite large which dictates that there is still room for improvement in the codes. Willemsen et al. [5] performed modelling of PTS situations by altering different terms of RANS model. RANS modelling techniques for the mixing of water in the reactor was used to get results. Comparison was done with values obtained from UPTF test centre. The computational results were obtained by models of turbulence and by using CFX. The solution of the problem by CFX show results that changes needed in the models of turbulence especially in production term of turbulence. By considering it, stratification can be modelled correctly. Calculated values show a difference of 3% from the experimental values so overall results were in good agreement. Instead of the two-equation model, a model of Reynolds stress that is ꞷ based is more useful for oscillation in temperature of the downcomer. M. Sharabi et al. [2] performed a CFD study of PTS in RPV. A medium break LOCA was considered in one hot leg of a PWR. In this study, they used commercial software FLUENT to perform PTS analysis on a two-loop Westinghouse type RPV. Both symmetric and asymmetric injections were considered. Boundary conditions for the CFD study were obtained from RELAP5. SST-Kꞷ turbulence model was used for PTS analysis. Results of temperature distribution in the downcomer and cold leg of RPV at high constant pressure were obtained. Stresses at RPV wall were also measured by using Finite Element Analysis (FEA). Results from CFD study were applied to the RPV outer wall in ABAQUS for the FEA of RPV solid model. Results showed three-dimensional flow behaviour during mixing of fluids. The asymmetric injection produces high stresses on the RPV wall during FEA analysis. Shams et al. [8] performed direct numerical simulation method for the study of PTS. A lot of computational power is required for the solution of the real-life condition through DNS. Therefore, instead of taking the whole geometry of the vessel, a simplified geometry was considered. A flat cold leg of square shape and a rectangular downcomer were considered. The flow field was solved by two kinds of boundary conditions i.e. adiabatic and then isothermal, both conditions contain severe situations of conjugate heat transfer. The one-half portion of the domain was considered due to symmetric fluid flow. Results show that in the injection zone velocity changes are not considerable. Velocity changes occur in the major region of downcomer. Isothermal boundary condition occurs during the initial phase of PTS. Adiabatic condition arrives at the later stages of PTS in which thermal equilibrium was established in the domain. Results for the simplified model show the prime features of the heat transfer during PTS. Literature review shows that PTS is a highly 3D phenomenon and it cannot be predicted by 1D system codes like RELAP5, CATHARE, ATHLET and TRACE. Since 1D system codes only provide overall system response while for PTS study localized condition in cold leg and downcomer are required. Also, RANS CFD modelling is useful for various conditions of PTS modelling [1]. SST-kꞷ model is appropriate for the modelling of turbulence for PTS scenarios [7].

In this study, the aim was to computationally simulate the PTS transient in the RPV of a typical 330 MWe NPP after a medium break LOCA occurs in the hot leg using commercial CFD software FLUENT. The emphasis was on the CFD study of thermal-hydraulics of PTS. To validate the CFD methodology used, the results published by M. Sharabi et al. of temperature distribution in the cold leg and downcomer for asymmetric injection in the RPV were reproduced [2]. After validating the CFD methodology, it was applied on RPV of a typical 330 MWe NPP. Temperature distributions with respect to time in the cold leg and downcomer were obtained for the single-phase study. For structural analysis, results of pressure and temperature distributions of the transient were imported as loads in ANSYS Structural (transient) module. CFD investigation gives a more accurate and clear picture as compared to 1D system codes, as CFD results are 3D and more practical.

2 Transient description

Severe PTS transients occur due to LOCA in an NPP. Though a break can occur in both primary and secondary sides of RPV but break in the primary side can cause more damage than the secondary side. Since during a secondary break, better mixing occurs between injected water and hot water present in the cold leg [1]. For the current study, a proposed break is considered in the hot leg. When the break occurs pressure of the system reduces rapidly and water from the ECCS system is injected in the cold legs. Initially, high-pressure safety injection pumps (HPSI) are used which preserves the pressure of RPV. Once the pressure becomes constant, more water is injected from the ECCS through accumulators in both cold legs. CFD calculation begins at conditions close to PTS transient i.e. both HPSI and accumulator is injecting water in the stagnant cold leg. These conditions are used for the conservative study of PTS as if the flow is present in the cold leg then better mixing will occur between two fluids which would create small temperature gradients. Stresses will be less due to small temperature gradients. For asymmetric injection, out of two only one accumulator is injecting water in one cold leg. This condition will create a non-uniform mixing which will create more stresses. At the start of the simulation, RPV is considered to be filled with water. As we are considering a single-phase transient so the void fraction is zero in the system.

3 CFD methodology validation

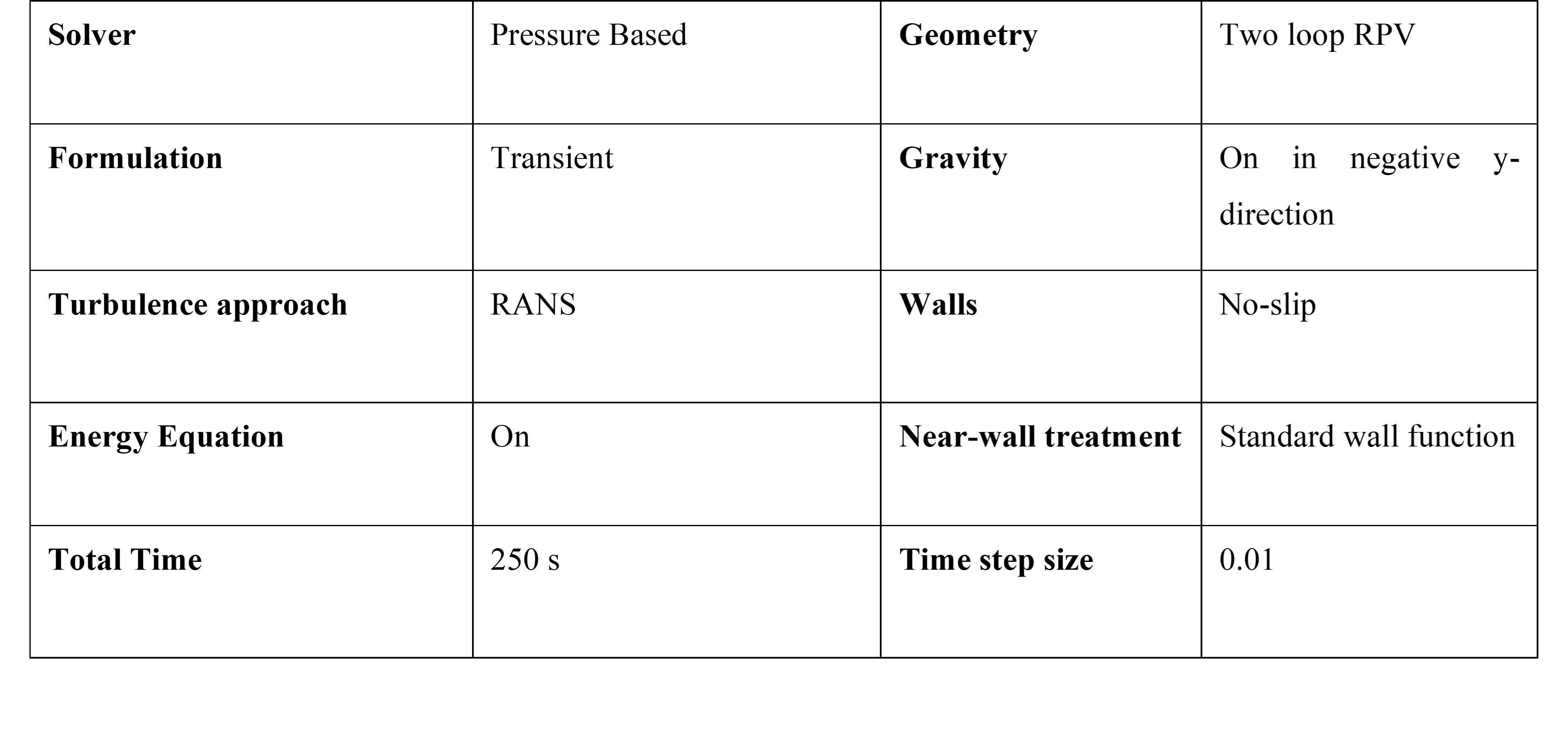

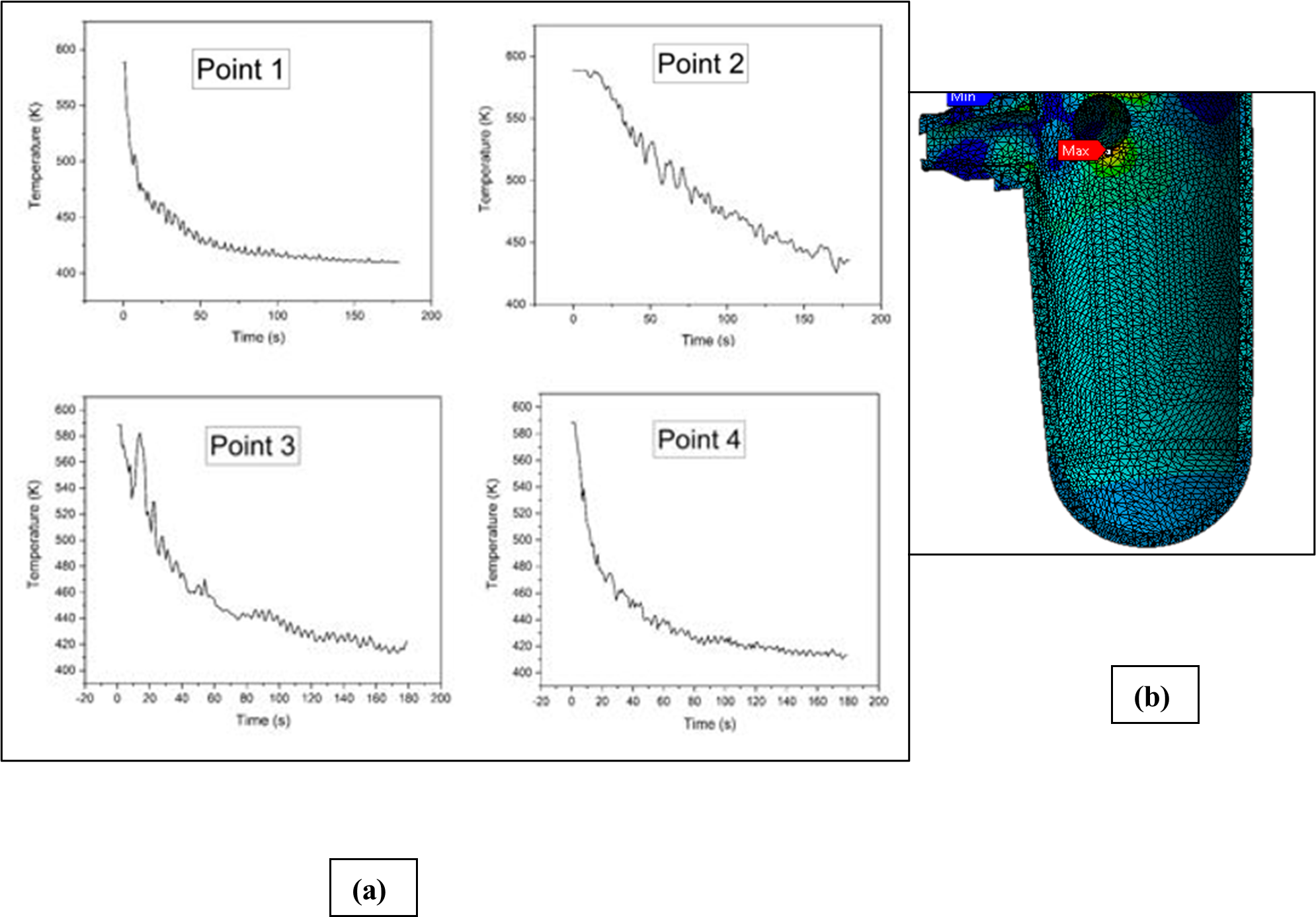

To develop CFD methodology, RPV geometry from the study performed by M. Sharabi et al. was selected [2] (Table 1). It is a two-loop Westinghouse type PWR. It contains two cold legs and four injection lines for the ECCS. The outlet is considered in the hot leg therefore hot leg is not shown in the RPV model. Structural details of the core are not considered because PTS is studied mostly in the downcomer and cold leg of RPV. Figure 1(a) shows the computational domain used by M. Sharabi in his research work.

3.1 Geometry

For the present case, geometry is a two-loop Westinghouse type PWR. A computer-aided design (CAD) file of geometry was created by using commercial CAD software. CAD file was imported in the ANSYS Design Modeler. Computational domain for fluid part contains two cold legs. ECCS water is injected in both cold legs by two injection lines opposite to each other named as HPSI and ACC. The computational domain also contains downcomer, lower plenum and the core of the RPV. It is shown in Figure 1(c).

3.2 Mesh and solver setup

The second step after creating geometry is meshing. First of all, a general mesh is created. Initially coarse and unstructured mesh was created through ICEM. Then the second mesh generated by slicing was fine and hybrid mesh. Mesh was created by using hexdominant method. It is shown in Figure 1(d).

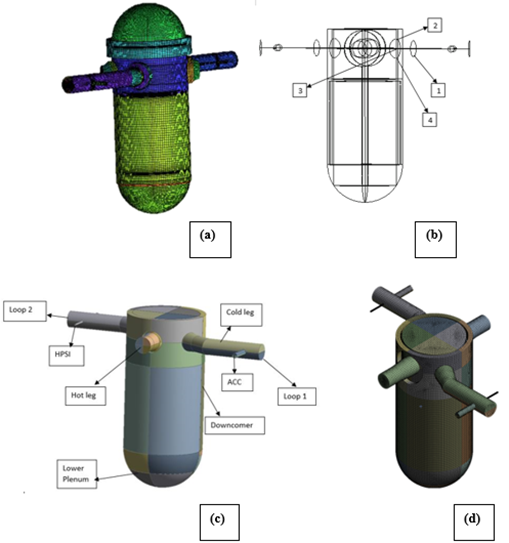

Tab. 1: Features of CFD model.

After meshing, the next step is the solver setup. In the present study, the FLUENT solver was used [9]. As the problem is of single-phase nature, so only one material was used i.e. liquid water. The pressure of the whole RPV initially was 70 bar. The temperature of the whole RPV was 558 K initially. Boundary conditions were applied at the inlets in the form of mass flow rates and pressure at the outlet. For asymmetric injection case, the mass flow rate of ACC1 is zero while remaining inlets are injecting water in the cold leg. The temperature of both accumulators are 283 K and both HPSI are 303 K. For turbulence modelling, an SST-Kꞷ turbulence model was used.

After meshing, the next step is the solver setup. In the present study, the FLUENT solver was used [9]. As the problem is of single-phase nature, so only one material was used i.e. liquid water. The pressure of the whole RPV initially was 70 bar. The temperature of the whole RPV was 558 K initially. Boundary conditions were applied at the inlets in the form of mass flow rates and pressure at the outlet. For asymmetric injection case, the mass flow rate of ACC1 is zero while remaining inlets are injecting water in the cold leg. The temperature of both accumulators are 283 K and both HPSI are 303 K. For turbulence modelling, an SST-Kꞷ turbulence model was used.

3.3 Results comparison and validation

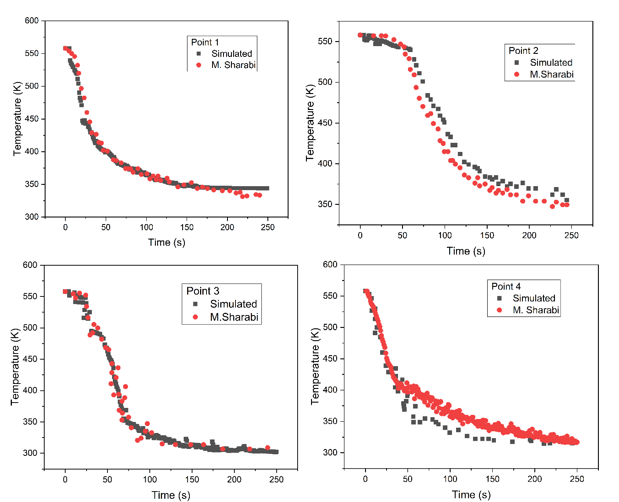

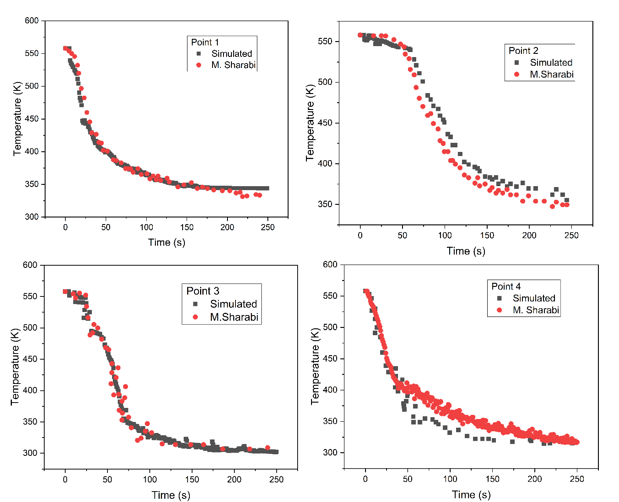

After completion of the simulations, results were obtained. For a transient simulation, the solution must converge at each time step. Calculated results include temperature distribution in the different parts of RPV. In order to validate the CFD methodology, temperature distribution versus time at various locations of RPV were plotted. Results obtained were compared with the results of temperature distribution versus time of M. Sharabi’s work [2].

Fig. 1: (a) M. Sharabi RPV model [2] (b) RPV examining locations (c) RPV simulated model (d) RPV fine mesh.

Various points were considered at the RPV wall in the cold leg and downcomer with only one point in the fluid region at the centre of the inlet nozzle connecting ring as shown in Figure 1(b). The simulated results and published results show similar temperature distribution in the RPV. Comparison of temperature Vs time plots of published and present CFD results are shown in Figure 2. Results of temperature distribution at RPV examining locations are similar to the published results. The error between simulated results and published results is less than 10 %. This shows that simulated results are in good agreement with published results.

Fig. 2: Comparison of temperature at various locations of RPV.

4 Typical 330 MW RPV

In this study, the aim was to computationally simulate the PTS transient in the RPV of a typical 330 MWe NPP after a medium break LOCA occurs in the hot leg using commercial CFD software FLUENT. Developed CFD methodology was applied to RPV of a 330 MWe NPP which is also a two-loop Westinghouse type PWR. It contains two cold leg and four injection lines for the ECCS. The outlet was considered in the hot leg and four injection lines of ECCS were considered as inlets. After creating geometry structured meshing was done on the RPV. Thermal hydraulics analysis was performed to obtain temperature distributions in the cold leg and downcomer of RPV. In addition, structural analysis was performed to obtain values of stresses in the cold leg and RPV inner wall. Results of temperature distribution and structural analysis were obtained.

4.1 Geometry

The geometry of 330 MWe NPP is a two-loop Westinghouse type PWR [10]. A CAD file of geometry was created by using commercial CAD software. CAD file was imported in the ANSYS Design Modeler. Computational domain for fluid part contains two cold legs. ECCS water is injected in both cold legs by two injection lines opposite to each other named as HPSI and ACC. Both these injection lines are at the same distance from the RPV outer wall. Each cold leg contains two parts. One part is straight while the other part is curved which is connected to RPV via the outlet nozzle. Downcomer is the part where water entering from the cold leg into the RPV flows. It starts from the inlet nozzle and ends at the lower plenum. For PTS study, this part is most significant. Initially, it is filled with hot water and cold water coming from ECCS mixes with hot water in the downcomer. The lower plenum is a hemispherical part. Water enters the core through the lower plenum. It is considered as smooth surface and structural details are neglected for this study. The computational domain also contains the core of the RPV. Structural details of the core are neglected as PTS effects are mostly studied at downcomer region.

For structural analysis, solid part of RPV was created. It consists of an RPV outer wall. Pressure load and thermal loads are applied to the whole computational domain. Solid RPV contains two cold legs and two injection lines opposite to each other in each loop. Structural details of the curved part of the inlet nozzle are very important because maximum stresses occur at the exit of this region and in the downcomer. Both fluid and solid part are shown in Figure 3.

Fig. 3: Geometry and mesh of 330 MWe RPV (left) fluid (right) solid.

4.2 Mesh and solver setup

The second step after creating geometry is meshing. First of all, a general mesh was created. Initially coarse and unstructured mesh were created. The unstructured mesh is used for complex geometries in FLUENT. Then the second mesh generated was fine and hybrid mesh. For this purpose, the whole computational domain was sliced into multiple parts. Due to the slicing, the meshing of the computational domain becomes easy. Meshing was created by using hexdominant method. The hybrid mesh contains mostly hexahedral elements and some tetrahedral elements. The cold leg contains some hexahedral elements while downcomer contains structural mesh and consists of all hexahedral elements. Lower plenum and core contains some tetrahedral elements but it is acceptable as PTS study is mostly done in the cold leg and downcomer region of RPV. The meshing of the solid part of RPV was done by using Transient Structural meshing tool. The computational domain of the solid part of RPV was sliced into multiple parts. Hexdominant method of meshing was used. The meshing of the solid part of RPV is difficult than the meshing of the fluid part of RPV. First of all coarse mesh was produced and then it was refined to produce a hybrid mesh. Hexdominant method is applied in different bodies separately to make a good mesh. Downcomer of the solid part contains hexahedral elements which are sufficient for PTS study.

After meshing, the next step is the solver setup. In the present study, the FLUENT solver was used [9]. As the problem is of single-phase nature, so only one material was used i.e. liquid water. Selection of density for complete simulation time is important, as large temperature gradient is present. A polynomial of density in terms of temperature was used for this reason. The temperature of the whole RPV was 588.5 K initially. Boundary conditions were applied in the form of mass flow rates at inlet and outlet boundary condition was taken to be pressure outlet. Mass flow rate was applied normal to the boundary at the inlets. For asymmetric injection case, the mass flow rate of ACC1 was zero while remaining inlets were injecting water in the cold leg. The temperature of both accumulators were 423 K and both HPSI were 408 K. SST-Kꞷ turbulence model was used for turbulence modelling

For structural analysis, Transient Structural code of ANSYS was used. Initial conditions were obtained from CFD analysis. Results of temperature and pressure distribution were imported into transient structural. Pressure load was applied at the inner of the RPV wall and thermal loads were applied to the whole computational domain. Structural analysis was performed to find the stresses developed in the RPV wall due to thermal and pressure loads. For this purpose, fixed support was provided at all the nozzles of geometry. After applying the fixed support, the inner RPV wall was formed. Thermal and pressure loadings were applied to this wall, which is a function of time. After applying initial conditions, the solution was started. Time step size for this analysis was set at 1.

5 Results and discussion

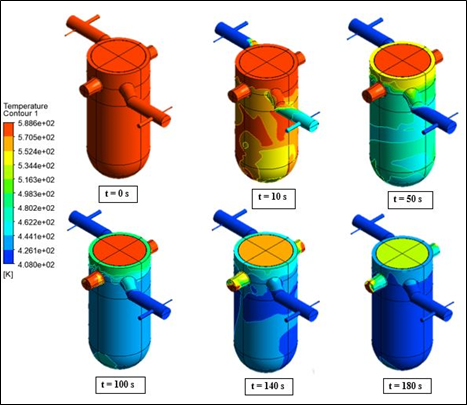

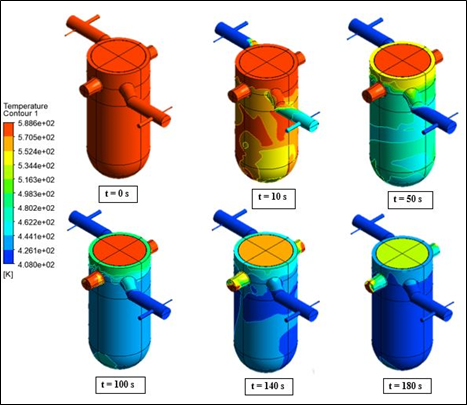

After completion of the simulations, contours of temperature were obtained at different time. The temperature of RPV drops gradually by cooling downcomer. Reactor pressure vessel outer surface is most vulnerable to thermal shock. When cold water is injected in cold leg, then water exists at two different temperatures in the cold leg. One is at high temperature while the second is at a lower temperature. Cold water due to its high density settle down in the cold leg and flows in the bottom region while cooling the hot water. Due to the high flow rate, mixing between cold water and hot water occurs. Plumes of cold water are formed and they strike with RPV wall. Due to this reason, PTS could occur because the wall is at high temperature and pressure while cold water is at low temperature. Interaction of cold water with hot water having high temperature and pressure could create large thermal stresses on the RPV wall and it can rupture. Calculated results include temperature distribution in the different parts of RPV. In the beginning, vessel consists of hot water only and there is no cold-water present inside the vessel. For the conservative study, all parts of the vessel are considered to be filled with hot water at high pressure and high temperature. When cold water is injected in the RPV through injection lines of accumulator and HPSI then it cools the cold leg and downcomer. Due to the density difference between cold water and hot water, cold-water flows in the form of a plume. Contours of temperature at various time steps (0 s, 10 s, 50 s, 100 s, 140 s and 180 s) are shown in Figure 4.

Fig. 4: Temperature contours of 330 MWe RPV at various time.

Cold plume enters in the RPV through inlet nozzle. RPV inlet nozzle is the part where the maximum temperature fluctuation is present as the flow separates into two parts after it. As the RPV wall is at a higher temperature when it interacts with cold plume it causes a large temperature gradient. At the end of the simulation, thermal stresses were significantly reduced.

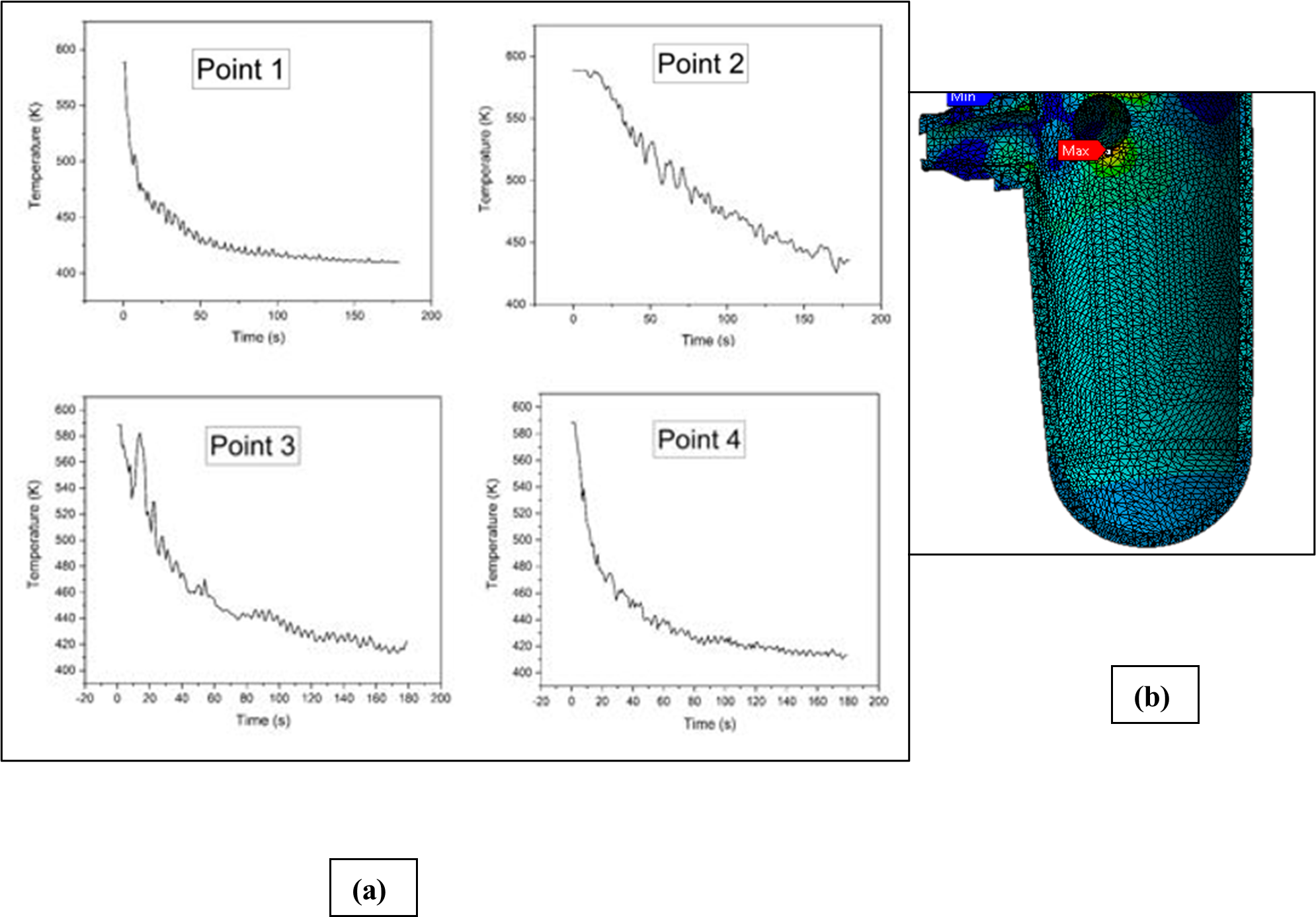

(a) |

(b) |

Temperature distribution versus time at various locations of 330 MWe RPV were plotted and shown in Figure 5(a). Point 1 is present in the cold leg, its temperature variation at the start is rapid, and then it slows down and become constant. It shows that better mixing occurs in the cold leg. Temperature distribution in point 2 shows a large difference in start up to 50 seconds then it begins to decrease gradually. Point 3 is present in the fluid and it has the largest fluctuation due to irregular movement of the cold plume at various time of the simulation. The temperature at point 4 is gradually decreasing as cold plume always stays attached to it. After thermal-hydraulics analysis, equivalent stresses were calculated by importing pressure and thermal loads on the inner RPV wall. Results of equivalent stresses for 330 MWe RPV show that the maximum stress region is at the inlet nozzle exit and entrance of the downcomer. It is shown in Figure 5(b). Major contribution of stresses comes from the thermal stresses while minor contribution comes from pressure loading.

Fig. 5: (a): Temperature plots at various locations of 330 MWe of RPV (b) stress contour.

6 Conclusion

First of all thermal-hydraulics analysis of PTS on the RPV was simulated. Contours of temperature were obtained at different time intervals and validated with the results available in literature. From this validation, CFD methodology was developed and then applied on typical 330MWe NPP RPV.

In typical 330 MWe NPP RPV, proposed break in the hot leg was considered. Asymmetric injection condition was considered to create non-uniform mixing which creates more stresses. Boundary conditions of mass flow rate and temperature were applied. Results of temperature distribution with time were obtained. The temperature of RPV drops gradually by cooling downcomer. Interaction of cold water with high temperature and pressure hot water create large thermal stresses on the RPV wall and it can rupture if it is beyond safety limit. After the thermal hydraulics, structural analysis of 330 MWe NPP RPV was done and the value of stresses was obtained. It was also noted that the maximum stress region is the region of the entry into the downcomer and exit of the inlet nozzle. RPV inlet nozzle region maintenance must be done at all time to avoid PTS. CFD simulations showed the three-dimensional conduct of the flow area and temperature distributions in the RPV.

7 References

[1] C. Boyd, “Pressurized Thermal Shock, PTS,” Semin. Transf. Competence, Knowl. Exp. gained through CSNI Act. F. Therm., pp. 463–472, 2008.

[2] M. Sharabi, V. F. González-Albuixech, N. Lafferty, B. Niceno, and M. Niffenegger, “Computational fluid dynamics study of pressurized thermal shock phenomena in the reactor pressure vessel,” Nucl. Eng. Des., vol. 299, pp. 136–145, 2016.

[3] V. F. González-Albuixech, G. Qian, M. Sharabi, M. Niffenegger, B. Niceno, and N. Lafferty, “Comparison of PTS analyses of RPVs based on 3D-CFD and RELAP5,” Nucl. Eng. Des., vol. 291, pp. 168–178, 2015.

[4] D. Lucas et al., “An overview of the pressurized thermal shock issue in the context of the NURESIM project,” Sci. Technol. Nucl. Install., vol. 2009, 2009.

[5] S. M. Willemsen and E. M. J. Komen, “Assessment of RANS CFD Modelling for Pressurized Thermal Shock Analysis,” Proc. 11th Int. Top. Meet. Nucl. React. Therm., pp. 1–15, 2005.

[6] T. Höhne, E. Krepper, and U. Rohde, “Application of CFD codes in nuclear reactor safety analysis,” Sci. Technol. Nucl. Install., vol. 2010, 2010.

[7] P. Apanasevich, P. Coste, B. Ničeno, C. Heib, and D. Lucas, “Comparison of CFD simulations on two-phase Pressurized Thermal Shock scenarios,” Nucl. Eng. Des., vol. 266, pp. 112–128, 2014.

[8] A. Shams, D. De Santis, D. Rosa, T. Kwiatkowski, and E. J. M. Komen, “Direct numerical simulation of flow and heat transfer in a simplified pressurized thermal shock scenario,” Int. J. Heat Mass Transf., vol. 135, pp. 517–540, 2019.

[9] Ansys Fluent 14.0: Theory Guide | Fluid Dynamics | Turbulence.

[10] Final Safety Analysis report,’ PAEC, May 2011.

![Fig. 1: (a) M. Sharabi RPV model [2] (b) RPV examining locations (c) RPV simulated model (d) RPV fine mesh.](https://atw-scientific.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/Fig.-1-3.png)

0 Comments