Preliminary CFD analysis of innovative decay heat removal system for the European Sodium Fast Reactor Concept

1 Introduction

Sodium-cooled Fast Reactors (SFRs) are among the most advanced concept of the Generation-IV reactor systems [1] with extensive design, construction, operation and decommissioning experience. Several experimental, prototype and power reactors have been built in Europe and elsewhere [2]. Currently, there are two commercial operating SFRs in Russia as well as experimental reactors operating in China and India. SFRs have several attractive features which allow them to meet the Generation-IV International Forum (GIF) objectives for future nuclear energy systems in terms of safety, sustainability, economics and proliferation resistance. The fast neutron spectrum in connection with low neutron absorption and low moderation characteristic leads to enhanced neutron economy, which allows in addition to efficient fission power generation, the breeding of nuclear fuel and burning of transuranic and minor actinides. In addition, the outstanding heat transfer property of sodium enables the design of a compact reactor core and high-performance, low-pressure heat transfer system. The SFR technology is in particular suitable to meet the twin missions of sustainability and improved economics both by efficient resource utilization and the effective management of plutonium and other minor actinides in a closed fuel cycle and by efficient power production using innovative power conversion systems.

The current SFR technology R&D focuses on innovations to improve plant economics by enhancing reliability and reduction of capital cost as well as to enhance safety up to the level of the requirements for the Generation-IV plants. The safety goals for Generation IV reactors require excelling in safety and reliability; the reduction of the likelihood and degree of reactor core damage; and the elimination of the need for offsite emergency response.

In order to meet these goals innovative safety concepts are needed in all areas of safety design of the fundamental safety functions. Beside reliable and robust reactivity control mechanism, highly reliable heat removal systems for assuring adequate cooling of safety relevant components and structures and effective options for dealing with severe accidents need to be implemented.

Within the FP7 Euratom project CP-ESFR [3], the concept of the European Sodium-cooled Fast Reactor (ESFR) has been proposed and is currently being further improved within the Euratom Horizon-2020 project ESFR-SMART [4] where new safety provisions have been proposed considering safety objectives envisaged for Generation-IV reactors and the update of European and international safety frameworks [5], taking into account the Fukushima accident. The proposed measures aim at enhancing safety and improving the robustness of the safety demonstration. The ESFR-SMART project aims to improve the reactor safety to the level of the requirements for the Generation-IV reactors, and make a proposal for new safety options, based on both present and previous projects experiences.

In line with these objectives, several innovative approaches to the safety design of the ESFR concepts are being investigated. One of the safety innovations concerns the re-placement of the safety vessel with reactor pit which is able to provide improved operational and safety functions of both the decay hear removal system and the containment function. With this innovation, the aim is to discard the safety vessel and to keep its safety functions, i.e., containment of the primary sodium in case of the reactor vessel leak without reduction of the primary sodium free level below the intermediate heat exchanger windows, by modifying the reactor pit geometry and by using the metallic liner on the reactor pit surface. In addition, this approach provides options to implement a new decay heat removal option within the reactor pit. With the implementation of this decay heat removal system, an additional safety provision is provided which could allow to practically eliminate a major safety design concern for sodium cooled fast reactors that of the prolonged failure of the decay heat removal function.

This paper discusses the preliminary CFD analysis of the design of the innovative decay heat removal system implemented in the reactor pit which consists of oil and water based loops that provides capability to remove the entire decay heat of the reactor. Furthermore, the paper explains the overall design of the reactor pit including the preliminary parametric calculations of temperature distributions for various design scenarios. The efficiency of the oil cooling system is evaluated. A representative part of the reactor pit structure is modelled. The heat path is from the reactor vessel wall through a gap, an insulation layer into a concrete structure. The heat sinks are the oil cooling system and the ambient. The oil cooling system is situated at the metal liner which is mounted along the insulation layer. In the gap. A simplified case is used for verification with an analytical solution. Furthermore, it is shown that the oil cooling system is capable to remove the heat from the structure and keep the temperature there below 70 degrees Celsius. At nominal conditions about 3 MW have to be removed and at a top cooling temperature of approximately 200 degrees.

2 ESFR System layout

2.1 ESFR design approach

The ESFR concept has been developed within the FP7 CP-ESFR project (2009 – 2013), considering past European experience in SFR technology in particular in the French SPX2 project and in European Fast Reactor project which involved a wider European cooperation. For both projects, the operational experience of the Superphenix reactor SPX [6][7] provided valuable inputs to improve safety, reliability, in service inspection and repair and economics.

The ESFR concept is a large pool type industrial Sodium Fast Reactor of 1500 MWe/3600 MWt. The design objectives for ESFR include simplification of structures, improved In-service inspection and repair capabilities, reduction of risks related to sodium fires and to the water/sodium reaction, improved fuel maintenance, core catcher with the capability for a whole core discharge and improved robustness against external hazards [5]. The ESFR core is composed of two zones of inner and outer fuel assemblies, and 3 rows of reflectors. There are two independent control rod assembly systems with additional passive reactivity insertion mechanisms. The core design aims at a fuel management scheme with a flexible breeding and minor actinide burning strategy.

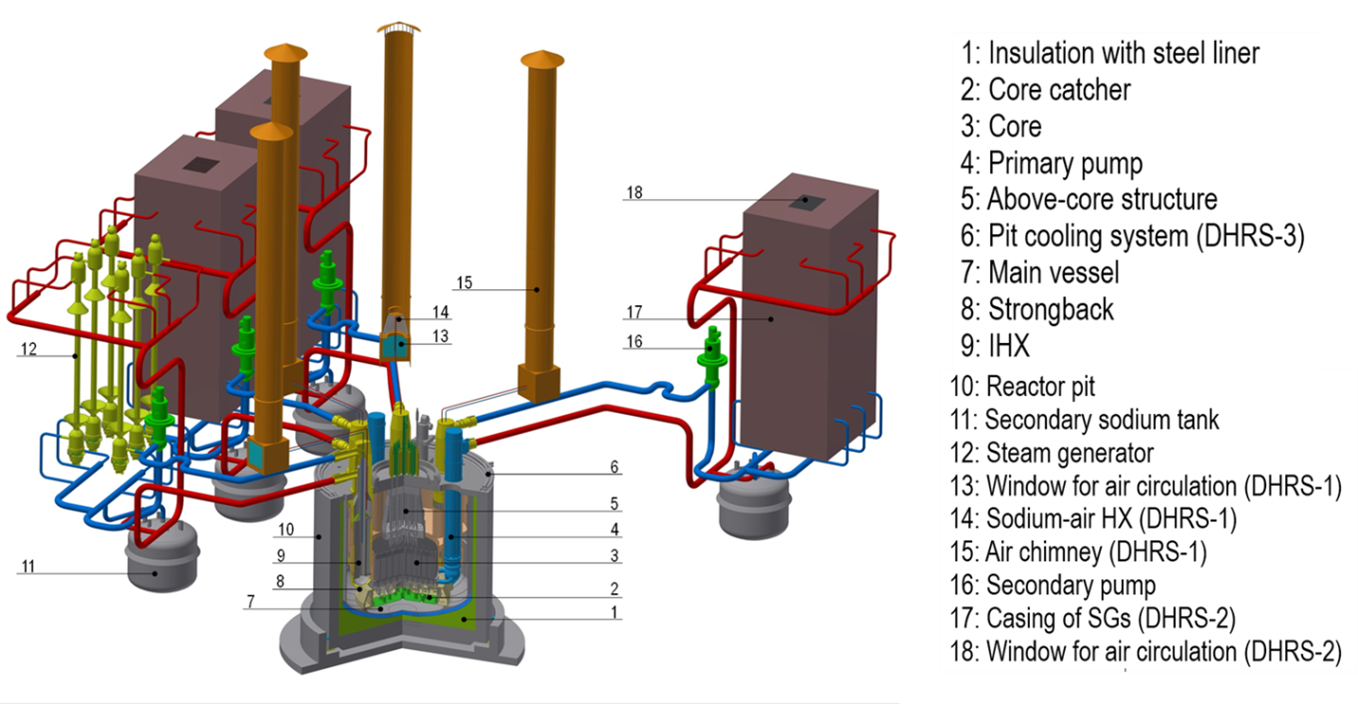

The ESFR concept plant layout is sketched in Figure 1. It is based on options already considered in previous and existing pool sodium fast reactors, with several potential improvements regarding safety, inspection and manufacturing. A particular attention is also given to compactness. The reactor vessel is cooled with sodium (submerged weir) and is surrounded by a reactor pit which replaces the safety vessel including all its function for normal operation and accident conditions. The reactor vault can be inspected for maintenance.

Figure 1 ESFR concept plant layout

The secondary system comprises six 600 MWth parallel and independent sodium loops, each connected to an intermediate heat exchanger (IHX) located in the reactor vessel. Each loop (see Figure 1) includes one Mechanical Secondary Pump (MSP), modular Steam Generators (SG) and one Sodium Dump Vessel (SDV). In addition to the normal power removal, the secondary system provides the DHR function in case of primary pumps trip.

The main design objective for the Decay Heat Removal (DHR) system is to practically eliminate the prolonged loss of the decay heat removal function. In order to achieve this objective, three independent DHR systems have been implemented (see Figure 1). The first DHR system, DHRS-1, is provided by sodium/air heat exchangers connected to each IHX. These loops replace the Direct Reactor Cooling (DRC) System in the previous design and have various advantages such as avoiding additional roof penetrations and maintaining cold column in the IHXs [5]. The second DHR system, DHRS-2, is provided by cooling the steam generator modules by air in natural or forced convection through hatch openings, as is done in the Phenix reactor, providing the heat sink for the secondary loop. The third DHR system, DHRS-3, is implemented in the reactor pit with two independent cooling circuits, one with oil heat exchanger brazed on the liner and one with water inside the concrete. The water loop is capable to maintain the whole pit at temperatures below 70°C. Due to the removal of the safety vessel, the DHRS-3 which is directly attached to the liner is expected to be more efficient and to assure a large part of the Decay Heat Removal close to 100%.

The safety analyses being currently performed indicate that with the current DHR concept the demonstration of practical elimination of a prolonged loss of the DHR function is feasible.

2.1 Description of the reactor pit design

One of the main innovative approaches to the safety design of the ESFR concept concerns the replacement of the safety vessel with reactor pit that aims to improve the operational and safety functions of both the decay heat removal systems and the containment.

All existing SFRs have a safety vessel (see an example of Superphenix safety vessel Figure 2) around the main vessel. The function of this safety vessel is to confine the primary sodium in case of the main vessel leakage, so as to avoid lowering of the primary sodium free level below the inlet windows of the intermediate heat exchangers and thus to provide an efficient natural convection through the core. In case of the main vessel leakage, the reactor is not recoverable and the core must be unloaded. Due to the need to wait for reduction of the residual power of the assemblies, this handling could take a significant duration (i.e. higher than one year) especially in the ESFR-SMART design without external sodium storage. The safety vessel must therefore remain filled with sodium for a long time. The potential danger in these conditions is that the reactor pit is not designed to withstand a sodium leak from this safety vessel. Moreover, this safety vessel leak would also lead to interruption of the core cooling by natural convection, leading to a very difficult overall situation.

A number of measures have been taken to prevent leakage of the safety vessel: slight overpressure between the two vessels to detect a possible leak and choice of different materials to avoid a common failure mode on corrosion. It is recalled that it is a problem of corrosion on welds that led to the leakage of the Superphenix storage drum vessel, and that this leak was taken up by the safety vessel of this storage drum [3].

The scenarios of vessel leakage are diverse, from corrosion leakage to leakage on a severe accident with mechanical energy release. This leads to high uncertainties in the temperatures and leakage rates, which make it difficult to demonstrate the safety vessel mechanical strength against the corresponding thermal shocks. Moreover, the French licensing authority requires considering the double leakages in order to verify that the situation does not lead to cliff-edge effect in term of radiological releases in the environment. This demonstration was required after the SPX external sodium storage leak. It is particularly required if the core unloading is high.

The safety vessel is a proven option, especially demonstrated during the incident at the Superphénix storage drum [6], and is adopted in all existing fast reactors. However, the evolution of safety standards leads us to look at other options where its functions could be directly taken over by a reactor pit capable of withstanding a sodium leak, and thus a long-term mitigation situation. It was an option that had already been looked at in the EFR project with a vessel anchored in the pit, which option was later abandoned for reasons of feasibility and design difficulties.

Figure 2: Arrival of the safety vessel inside the reactor pit of Superphenix

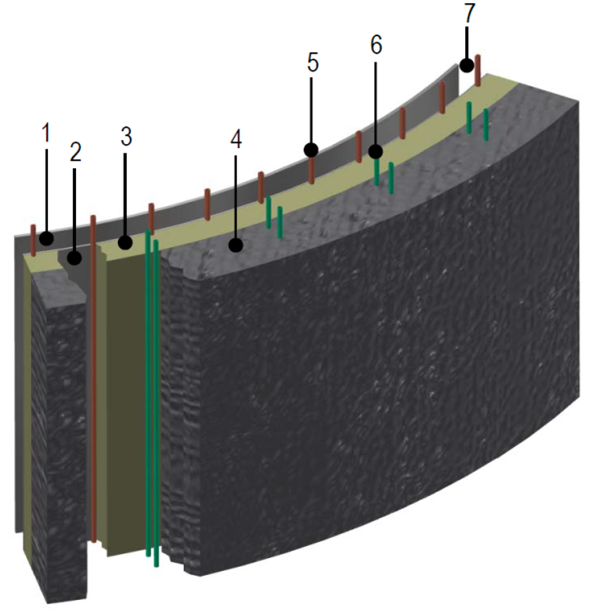

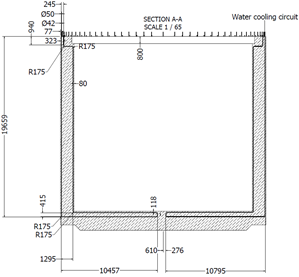

The proposed design of the reactor pit is composed of the following domains (see Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 5):

- A mixed concrete/metal structure with a water cooling system inside the concrete supports the thick metal slab to which the reactor vessel is attached. Together with the reactor roof, it provides a sealed containment which must keep its integrity in all the cases of normal or accidental operations [1].

- Inside the concrete/metal structure, blocks of insulating materials (non-reactive with sodium) are installed. Alumina is selected as reference material for the insulation blocks. A conventional insulation layer could be considered in future to increase insulation effects (outside the scope of the paper).

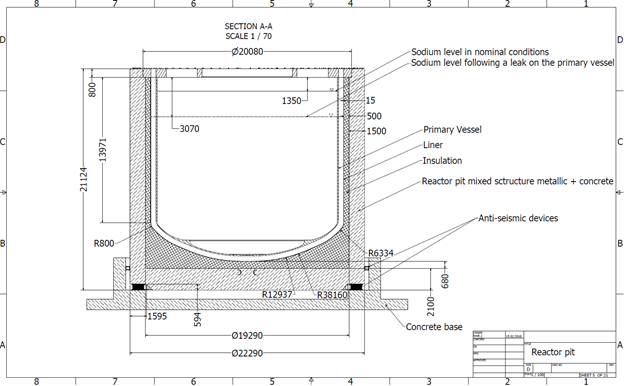

A metallic liner is placed on the surface of the insulation blocks. The gap between the reactor vessel and the liner must be small enough (350 mm was chosen) to avoid decrease of the primary sodium free level below the intermediate heat exchanger (IHX) windows in case of sodium leakage from the reactor vessel. During normal operation, the primary sodium free level is 1350 mm below the roof. In case of primary sodium leak about 300 m3 of sodium will leave the reactor vessel to fill the gap and the new equilibrium free level of the primary sodium will be about 3070 mm below the reactor roof. With this level of sodium inside the primary circuit, there is still a 1090 mm sodium level above the upper IHX openings, which allows a sodium inflow into the IHX and a good natural convection and core cooling. If the sodium temperature decrease to 180°C , the volume of remaining sodium will decrease of about 205 m3 due to the change in the density, It would cause the sodium level to go down to around 50mm above the IHX entry bottom. And the natural convection remains possible.

- The oil cooling system is installed next to or even inside the liner (Figure 3).

- Finally, a special concrete with alumina (aluminous concrete) which could withstand, without significant chemical reaction with sodium, a leakage of the liner could be used between the liner and the insulation (blocks of alumina).

Two independent active cooling systems are proposed in the reactor pit (we use the acronyms DHRS-3 for the combination of these two systems):

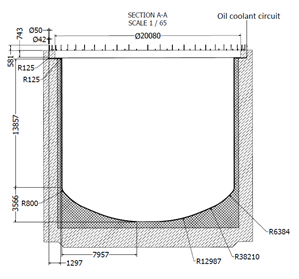

- The oil cooling system (DHRS-3.1) close to the liner (Figure 4a). The oil under forced convection can remove the heat transferred by radiation from the reactor vessel at high temperature. Conversely to water, the adopted synthetic oil is resistant to high temperatures above 300°C and reacts with sodium without producing hydrogen. As an example the commercial oil called ”Therminol SP“ [8] can be used in normal operation at temperatures up to 315°C.

- The water cooling system (DHRS-3.2) for the concrete cooling is installed in the concrete (Figure 4b) and aims at maintaining the concrete temperature under 70°C in all possible situations, even if the oil system is lost.

Both oil and water circuits work during normal operation and have to maintain the concrete temperature below 70°C. This margin is intended to ensure the concrete integrity and to protect it from thermal degradation. During the reactor shutdown the oil system alone has to be able after few days to remove all the decay heat generated by the fuel. In case of the reactor vessel leak and loss of the oil system, the water system should be able to remove the decay heat generated by the core and to maintain the concrete below 70°C.

Figure 3: Detail of the reactor pit design (1 reactor vessel, 2 liner, 3 insulation, 4 concrete/metal structure, 5 oil cooling system (DHRS-3.1), 6 water cooling system (DHRS-3.2, 7 gap)

Figure 4: Drawing of the reactor pit design

Figure 5: Drawings of the reactor pit cooling systems: (a) oil and (b) water

2.2 Main design-basis scenarios

The reactor pit must be designed for the following three main scenarios:

- Scenario 1: Normal operation: The main vessel temperature is at about 400°C. The operation of the oil cooling system is sufficient to maintain the correct thermal conditions in the pit (e. less than 70° C for the concrete of the mixed structures).

- Scenario 2: Operation in exceptional decay heat removal regime: The safety studies should take into account exceptional situations of successive losses of decay heat removal systems. In this case, in exceptional situations of Categories 3 and 4, the reactor vessel is allowed to reach temperature of 650°C. The two cooling systems (oil and water) must make it possible to maintain the concrete temperature below 70°C while playing an important role in the decay heat removal (in this study only the oil cooling system is taken into account; further publication is following).

- Scenario 3: Operation in accident situation of sodium leakage: In a situation of little leak, vigorous sodium cooling is possible with the redundant and available DHRS, to bring the sodium to a temperature corresponding to the handling temperature (180°C).Therefore, the maximum temperature of the sodium in the gap should not exceed 200°C. The demonstration of the oil cooling system availability in case of reactor vessel leakage is difficult and we assume as hypothesis that the oil cooling system is no longer available. The operation of the water cooling system alone must be sufficient to maintain the concrete temperature below 70°C (further publication).

NB: But other studies need later to be performed, taking in account a leakage (or combined) due to a high thermal transient (e.g., due to failure of DHR system) and if the failure is due to the severe accident. In this case the sodium temperature will be higher

3 Computational Fluid Dynamics Analysis

3.1 CFD model

The objective is the development of a simple Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) model to compute the steady-state heat transfer from the reactor vessel through the reactor pit. The computations are performed with ANSYS CFX which is a parallelized high-performance CFD software tool [9]. The steady-state model is based on finite volume technique applied to solve the Navier-Stokes equations. To achieve results with low computation time, the reactor pit is divided into several sections and the CFD analysis is performed for every section. The drawing of the geometry for one section, the “elementary cell” of the reactor pit structure, is shown on Figure 5. For the calculation example, the oil cooling system is installed inside the liner of the special wavy shape (see Figure 6).

The following simplifications and assumptions are applied at this stage of computations:

- The gap between the reactor vessel and the liner is considered as vacuum for first CFD computations to minimize the CPU time.

- The material of the insulation layer is assumed to be glass wool for the current study.

- Only steady state computations are performed.

Fast solution is important to be able to perform the large amounts of parametric studies. The resulting CFD model geometry is shown on Figure 6. The domains for the model are as follows (l is the thermal conductivity):

- The outer surface of the reactor vessel wall is shown on the left-hand side (red).

- The gas gap (white); l = 0.026 W m-1 K-1. However, for the computations nearly-vacuum is assumed here as worst case and the heat transport parameters (density and specific heat) are set to very low values and the solution of the flow is switched off.

- The stainless steel liner of the wavy shape is proposed (blue); l = 60.5 W m-1 K-1 with the pipes of the oil cooling system inside (dark blue).

- The insulation layer (yellow); l = 0.04 W m-1 K-1.

- The concrete structure (grey); l = 1.4 W m-1 K-1.

- The right-hand side surface interfaces the environment (black).

The boundary conditions for the CFD model on Figure 6 are as follows:

- Fixed temperature of the reactor vessel wall (red surface at the left) for different axial levels (Tvw = 400, 500, 600 and 700°C). This is intended to represent the different levels of the heat source inside the vessel.

- The heat sink is the environment outside of the concrete structure (black surface at the right). As a first approximation the following data is taken for the heat transfer: Ta = 50°C, k = 6 W m-2 K-1, where k is the heat exchange coefficient. For later calculations, the heat sinks will include the water cooling system.

- The other outer surfaces are defined as “symmetric”, e. adiabatic.

Calculations were made first without taking into account the oil cooling system in order to see if one could reach, with the only heat removal to the environment, required temperature level in the concrete domain.

Figure 6: Drawing of an “elementary cell” of the reactor pit model

Figure 7: The CFD model of an “elementary cell” of the reactor pit model

3.2 Analytical solution for verification

The current CFD model without local heat sinks (the cooling systems) is convenient for verification by comparison to an analytical solution. This requires one-dimensional model of the heat transfer by radiation in the gap and by heat conduction in the solids. The heat path is from the hot reactor vessel wall towards the outer concrete surface facing the environment. The heat flow due to radiation in the gap between a hot surface (index 1) and a cold surface (index 2) can be written as:

(1) |

Hereby T is the (absolute) temperature and σ = 5.67⋅10-8 W m−2 K−4 is the Stefan–Boltzmann constant. Assuming emissivity of stainless steel for both surfaces (ε1 = ε2 = ε = 0.4, a typical value for stainless steel) and full visibility (F12 = 1) and for A1 ≈ A2 = A the temperature of the cold surface yields:

(2) |

Heat conduction through a cylindrical solid wall in direction of the radius r can be written as

(3) |

Hereby l is the thermal conductivity of the solid and A(r) = 2prh the cylindrical surface at the radius r and for a segment of the height h. The integration between the radii r1 and r2 with the corresponding temperatures T1 and T2 yields the temperature at the outer radius

(4) |

3.3 CFD results without the cooling system

For this computation the oil cooling channels in the liner on Figure 6 are not taken into account. The liner is considered to be flat (equal thickness) and without pipes. The temperature along the heat path in the centre of the domains is shown on Figure 7. On Figure 7a, the constant-temperature boundary condition is applied at the primary vessel wall (Tvw = 400, 500, 600 and 700°C, red surface on Figure 6). In the nearly-vacuum domain of the gap the heat transfer takes place by means of radiation and the temperature is almost identical to the boundary condition. The temperature of the metal liner is also very close to the temperature of the vessel (since the cooling system is not modelled in this case). As expected, the main temperature drop takes place in the insulation layer. However, the temperature in the concrete is mostly above the required limit of 70°C as shown on Figure 7b. Furthermore, on Figure 7a and b the CFD results are compared with the analytical solutions of Eq. (2) and Eq. (4). The maximum deviation of the temperature is less than 5°C.

Figure 8: The temperature along the heat path (in x direction); computation (CFD) and analytical solution (Ana); a) the whole length; b) the concrete domain. The dotted red line denotes the temperature limit of 70°C.

3.4 CFD results with the cooling system

For this computation a constant average temperature Tcc at the oil cooling channel walls (Figures 5 and 6) is set as boundary condition. The aim is to understand the interaction between the reactor vessel wall temperature, the oil cooling system temperature, and the maximum concrete temperature. The final goal is to estimate the power removed by the oil cooling system.

On Figure 8 the temperature field for the computed elementary cell is depicted. The hot reactor vessel with the constant temperature of the vessel wall equal to Tvw = 700°C is on the left-hand side. The temperature of the oil cooling channel walls is set to Tcc = 200°C. Most of the heat transfer takes place between the vessel wall and the cooling channel. The maximum concrete temperature is slightly below 70°C.

On Figure 9 the temperature is shown along the main heat path (from the hot main vessel wall at the left towards the ambient on the right). On Figure 9a the temperature is shown along the x axis (symmetry centre line of the elementary cell) and along a line cutting the centre of one of the cooling channels. The case corresponds to the temperature field on Figure 8. As expected, the hottest location of the liner is at the centre line (maximum distance to the cooling channels). The temperature minimum is defined by the cooling channel temperature (Tcc = 200°C). On Figure 9b and 9c the temperature is given for four different vessel wall temperatures. For all cases, the concrete temperature remains below the limit (70°C) denoted by the red dotted line. The case with Tvw = 700°C corresponds to Figure 9a and to the temperature field shown on Figure 8.

On Figure 10a the maximum concrete temperature Tc is shown versus the cooling channel temperature for different vessel wall temperatures. The case discussed on Figure 8 and on 9a corresponds to the point Tvw = 700°C and Tcc = 200°C which is slightly below the dotted red line. Consequently, according to this model the temperature of the cooling channel wall has to be maintained below 200°C to keep the concrete temperatures below the limit. For lower vessel wall temperatures the cooling channel wall temperature can be higher.

Parametric calculations of the power removed by the oil cooling system at different vessel temperatures are shown on Figure 10b. They are evaluated with grey body factors of vessel and liner equal to 0.4 that is a typical value for stainless steel. If necessary this value could be increased by liner surface processing to increase its emissivity and the associated decay heat removal capacity. Calculations were performed for various oil temperatures (Figure 10b). An average temperature of about 200°C is proposed for operation which is far below the operating range of the “Therminol SP” oil (315°C).

The power removed by radiation from the reactor vessel at 400°C (~nominal core inlet temperature) is about 3 kW/m2 .The surface of the reactor vessel, radiating towards the oil cooling system, is about 1050 m2. So at nominal operation, approximately 3 MW will have to be removed in order to maintain the oil at an average temperature of approximately 200°C.

In exceptional regime of decay heat removal (situations in category 3 and 4) the system can then remove (the main vessel being at 650°C), a power of about 15 MW. This value doesn’t take into account the exchanges by gas convection between vessel and liner, and could be also increased by special processing of the liner surface to increase its emissivity coefficient. The value of 15 MW corresponds to the decay heat power level after about three days.

For Scenario 2 (See Section “Main design-basis scenarios”) we assume that the average oil temperature (and therefore the liner) is at ~200°C. For Scenario 3 we assume that the other DHRS guarantee that the primary sodium is at about 200°C and the oil system is out of operation, therefore the liner will be also at ~200°C. Thus, the conducted preliminary analysis based on the use of the oil cooling system alone is potentially applicable to all three scenarios. Nevertheless, the necessity of the water cooling system will be analysed at the next phase of the (more detailed) analysis.

Figure 9: Temperature field, Tvw = 700°C, Tcc = 200°C

- a) b) c)

Figure 10 Temperature profile along the x-axis for a cooling channel temperature of Tcc = 200°C.

- a) b)

Figure 11: a) The maximum concrete temperature and b) Power removed by the oil cooling system at different temperatures of the reactor vessel and the oil cooling channel wall

NB: thermal exchange have been calculated only with radiative and conduction effects. The exchanges by convection have not been taken in account and should be estimated later.

4 Conclusion

Within the Euratom H-2020 ESFR-SMART project, various design options have been proposed to improve the safety of the ESFR concept to the level of the requirements for the Generation-IV reactors based on both present and previous projects experiences. One of the main innovative approaches to the safety design of the ESFR concepts concerns the re-placement of the safety vessel with reactor pit in order to provide improved operational and safety functions of both the decay hear removal system and the containment. The focus of the present paper is the preliminary CFD analyses of the innovative decay heat removal design implemented in the reactor pit.

Two active (forced-convection) cooling systems are proposed: an oil cooling system close to the metallic liner and a water cooling system in the reactor pit concrete structure. The main goals of the cooling systems are:

- to keep the reactor vessel at acceptable temperature level and therefore provide its integrity and

- to maintain the concrete temperature below 70°C in the three scenarios of operation envisaged (normal operation, decay heat removal without and with primary sodium leak).

The conducted CFD analysis in the present paper is concentrated on the evaluation of the oil cooling system. It considers vessel wall temperatures up to 700°C. The main heat transfer mechanism from the wall towards a metal liner at the other side of the gap is assumed to be thermal radiation. It can be shown, in the scenarios studied, with the oil cooling system designed to keep the liner temperature at around 200°C, that this system alone can fulfill the goals to safely remove the residual heat of about 3 MW in nominal conditions and to maintain the temperature of the concrete of the reactor pit below 70°C in the two accidental situations. The water cooling system seems only a supplementary safety protection against any pit structure concrete damage and will be subject of further publication.

Acknowledgement

The research leading to these results has received funding from the Euratom research and training programme 2014-2018 under grant agreement No 754501.

5 References

- A Technology Roadmap for Generation IV Nuclear Energy Systems, S. Department of Energy Nuclear Energy Research Advisory Committee and the Generation IV International Forum (Dec. 2002).

- Aoto, K., et al., A summary of sodium-cooled fast reactor development, Prog. Ener. 77, 247- 265, (2014).

- L. Fiorini and A. Vasile, European Commission – 7th Framework Programme The Collaborative Project on European Sodium Fast Reactor (CP-ESFR), Nucl. Eng. and Des.241, 3461– 3469, (2011).

- Mikityuk, et al., ESFR-SMART: new Horizon-2020 project on SFR safety, IAEA-CN245-450, Proceedings of International Conference on Fast Reactors and Related Fuel Cycles: Next Generation Nuclear Systems for Sustainable, Development FR17, Yekaterinburg, Russia, 26-29 June, (2017).

- Guidez, A. Rineiski, G. Prêle, E. Girardi, J. Bodi, K. Mikityuk, Proposal of new safety measures for European Sodium Fast Reactor to be evaluated in framework of Horizon-2020 ESFR-SMART project, Proceedings of the International Congress on Advances in Nuclear Power Plants (ICAPP 2018), Charlotte, North Carolina, USA, 8-11 April ,(2018).

- Guidez and G. Prêle, “Superphenix. Technical and scientific achievements”, Edition Springer, ISBN 978-94-6239-245-8, (2017).

- Guidez, J., Gerschenfeld, A., Grah, A., Tsige-Tamirat, H., Mikityuk, K., Bodi, J., Girardi, E., “European Sodium Fast Reactor: innovative design of reactor pit aiming at suppression of safety vessel”, ICAPP 2019, May 12 – 15, Juan-les-pins, France.

- Therminol® SP Heat Transfer Fluid: https://www.therminol.com/products/Therminol-SP

0 Comments