Birte Froebus

–

Decommissioning and Waste Management

Research Assistant at Karlsruhe Institute of Technology, Karlsruhe, Germany

Article

–

–

–

–

Investigations of the Tailskin Seal During the Retrieval Concept ‘Shield Tunnelling with Partial Face Excavation’ in the Asse II Mine

Introduction

The Asse II mine is a former salt mine near Remlingen where potash salt was mined from 1909 to 1925 and rock salt from 1916 to 1964. After salt mining ceased, about 126,000 containers of low- and intermediate-level radioactive waste were stored between 1967 and 1978. Due to its high degree of excavation, the mine workings were damaged by pressure from the overburden. Saturated access water is penetrating through the cracks that have developed. In addition, the stability of the mine is deteriorating. The radionuclides from the present damaged waste packages could be transported into the environment via resulting pathways and transport media.

Due to the situation described above, long-term safety can only be guaranteed by retrieving the radioactive waste according to the current state of knowledge, which is why this has been stipulated by law since 2013. The adopted law ‚Lex Asse‘ creates an important legal basis for the retrieval of radioactive waste. Through simplified procedures and the possibility of carrying out work in parallel, the law makes it possible to accelerate the work. In addition, the public’s right to comprehensive information is strengthened. Despite all this, it should be mentioned that no practical experience has been gained so far for such retrieval from deep geological formations. In the event that the deformations caused by the rock pressure and the resulting solution influx exceed a manageable level and the mine has to be abandoned, there are explicit emergency measures. In this scenario, among other things, a targeted counterflooding of the entire caverns is initiated – in this case, the radioactive waste must remain in the mine and could not be retrieved. [1]

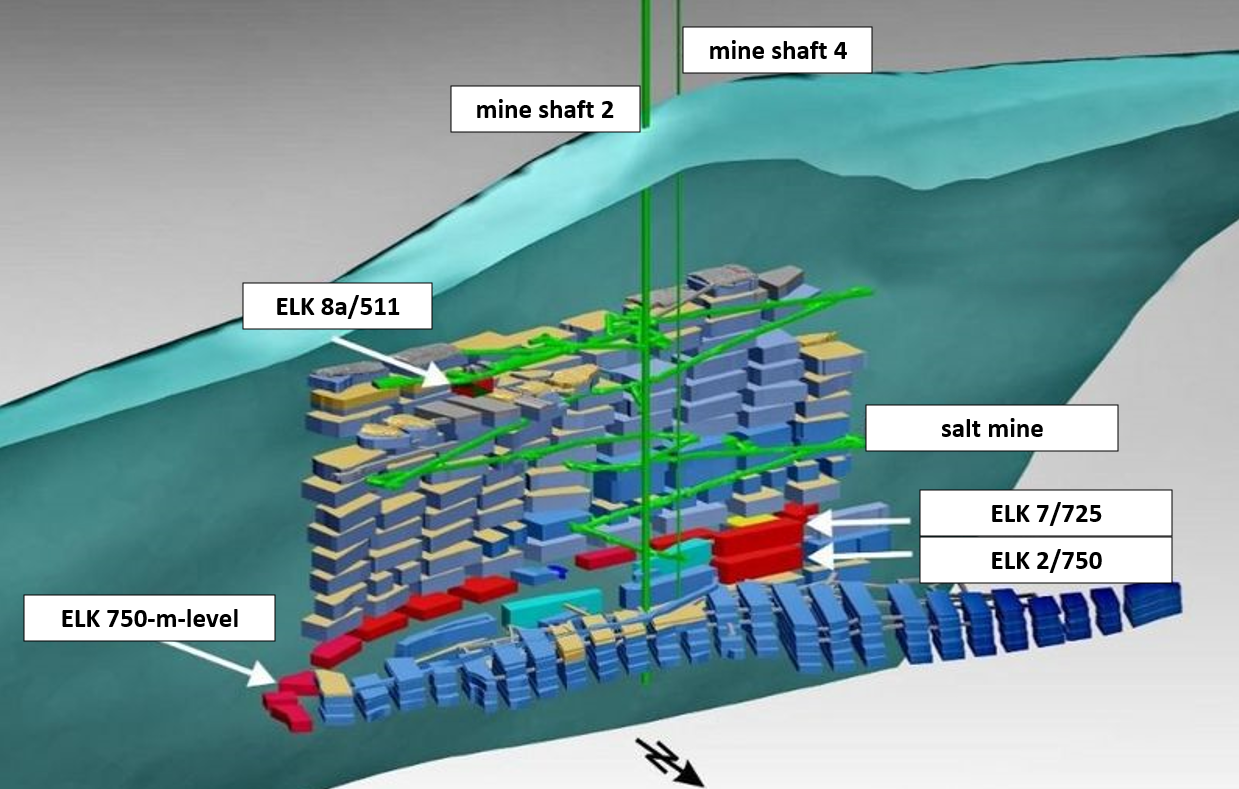

The radioactive waste in the Asse II mine is placed in a total of 13 ‚emplacement chambers‘ (German: Einlagerungskammer = ELK) on three levels at depths of 511 m, 725 m and 750 m, which are shown in red in Fig. 1. ELK 8a/511 is located on the 511-m-level and ELK 7/725 on the 725-m-level. The other eleven emplacement chambers 1/750, 2/750, 2/750 Na2, 4/750, 5/750, 6/750, 7/750, 8/750, 10/750, 11/750 and 12/750 are located on the 750-m-level. [1]

In this article, several terms related to mining are used to describe the mine. The emplacement chambers are located on several levels, so to say the floors of the mine. Between the chambers there are so-called pillars, i.e. the walls in the vertical direction, and the so-called roofs, i.e. the mighty ceilings in the horizontal direction. The pillars and the roofs are the remaining rock after the chambers have been created, which now represents the load-bearing structure in the mine building. Analogous to tunnelling, within the chambers the bottom is called the ‚floor‘ and the ceiling is called the ‚roof‘.

Fig. 1: Emplacement chambers on different levels in the mine workings of the Asse II mine [1]

Each of the three levels offers a different spatial situation, resulting in fundamentally different strategies for retrieval:

- ELK 7/725 is still accessible and is currently used as a storage facility for radioactive waste produced during operations. In addition, low-level radioactive material is stored there and the chamber is continuously ventilated. Therefore, the retrieval of this single emplacement chamber is to be started as planned. For this purpose, a ‚Long-front construction method with vertical excavation direction‘ is aimed at, which is based on mining extraction methods. For the recovery of the casks, i.e. for uncovering, loosening and loading; floor-operated technology is to be used. Transport, on the other hand, is to be carried out using decoupled ceiling-operated technology. [1]

- In ELK 8a/511, almost exclusively casks with intermediate-level radioactive contents were stored. This is also the reason for the special feature of this emplacement chamber: a charging chamber on the 490-m-level above the emplacement chamber, from which the casks were lowered into the emplacement chamber. Assuming that the emplacement chamber can be driven on the floor, only floor-based technology is to be used. [1]

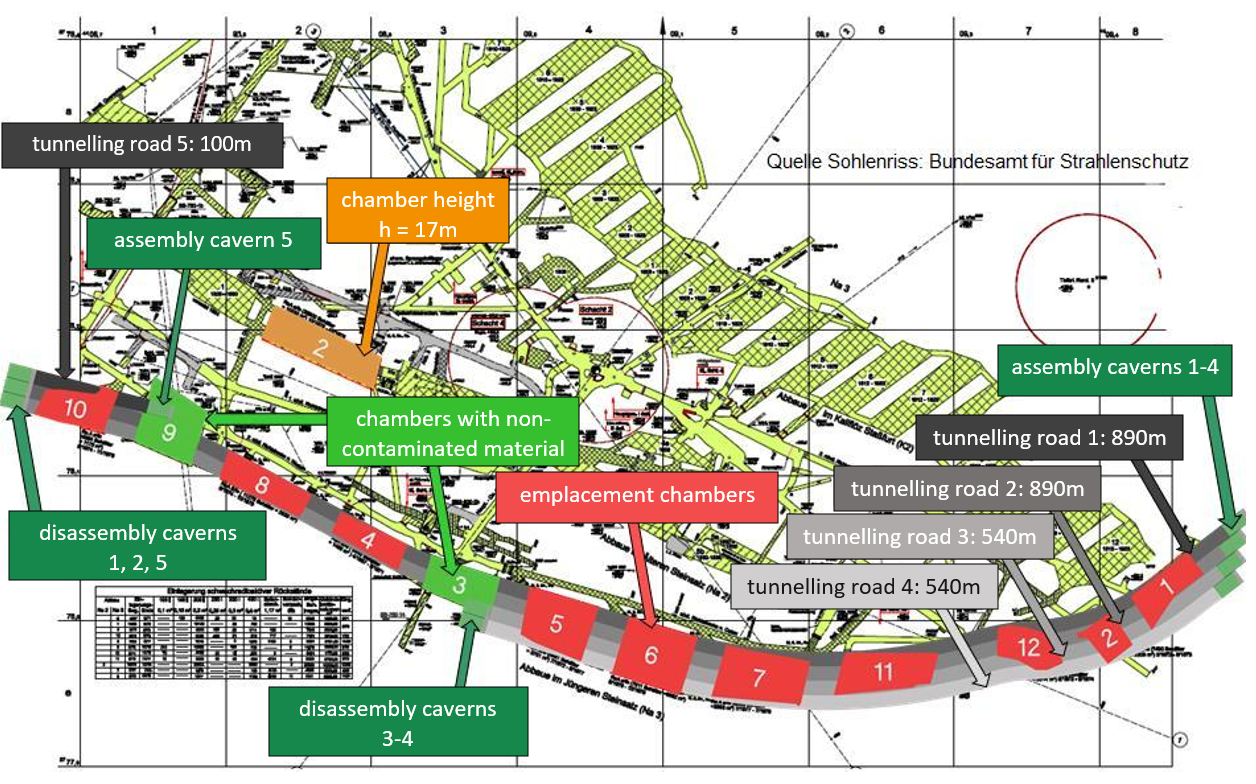

- The 750-m-level contains the majority volume of the radioactive waste, with eleven emplacement chambers containing low-level radioactive waste (see Fig. 2). Due to the different rockmechanical boundary conditions, the chambers are divided into three groups here. Here, the roofs in particular play a decisive role. In the central part of the mine buildings lies ELK 2/750 Na2, directly below ELK 7/725 and a roof of 6 m thickness. This roof is considered intact for retrieval, as ELK 7/725 will have been cleared and backfilled by that time. The roofs of the emplacement chambers of the chamber group ‚East‘ (ELK 1/750, 2/750, 12/750) are considered intact, as there are no voids above them on the 725-m-level. The remaining seven emplacement chambers of the chamber group ‚South‘ are closer to the overburden of the South flank and probably have unstable roofs. In contrast to the 511-m- and 725-m-levels, there is no final planning for the 750-m-level, instead there are several different approaches. On one hand, there are various possibilities to approach the chambers individually, on the other hand, there is a variant to approach the chambers one after the other along a curve. In the latter variant, only the chamber groups ‚South‘ and ‚East‘ can be taken into account, and a study has already been carried out on this issue. [1] In the further course of the article, only aspects of this return variant will be dealt with.

Retrieval of the chamber groups ‚South‘ and ‚East‘ (750-m-level) by means of ‘Shield tunnelling with partial face excavation’

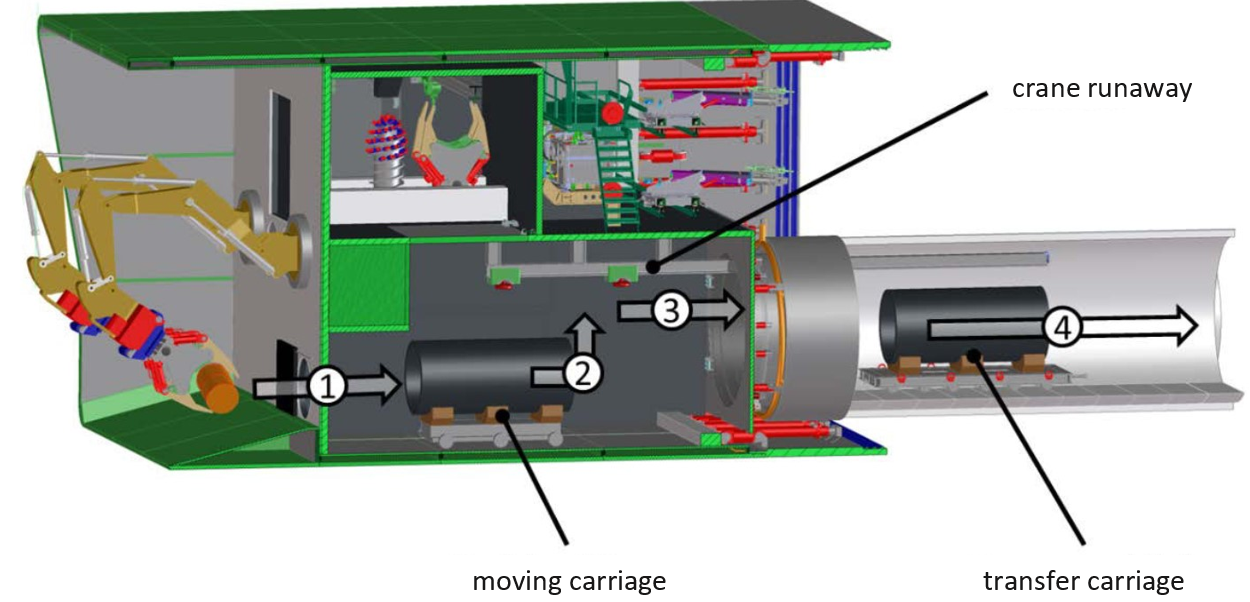

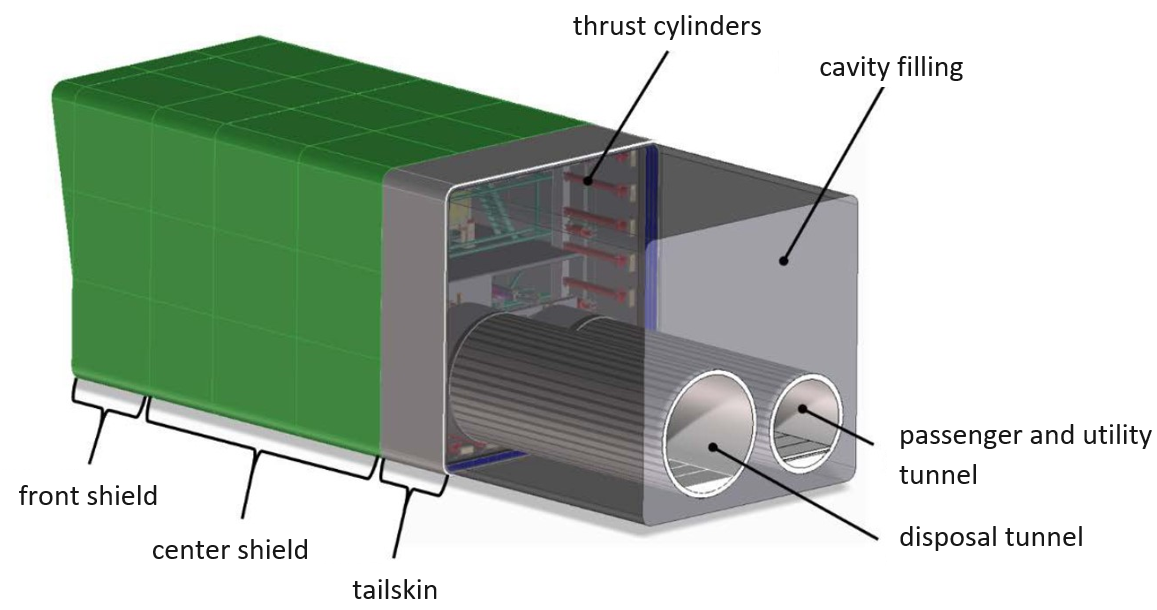

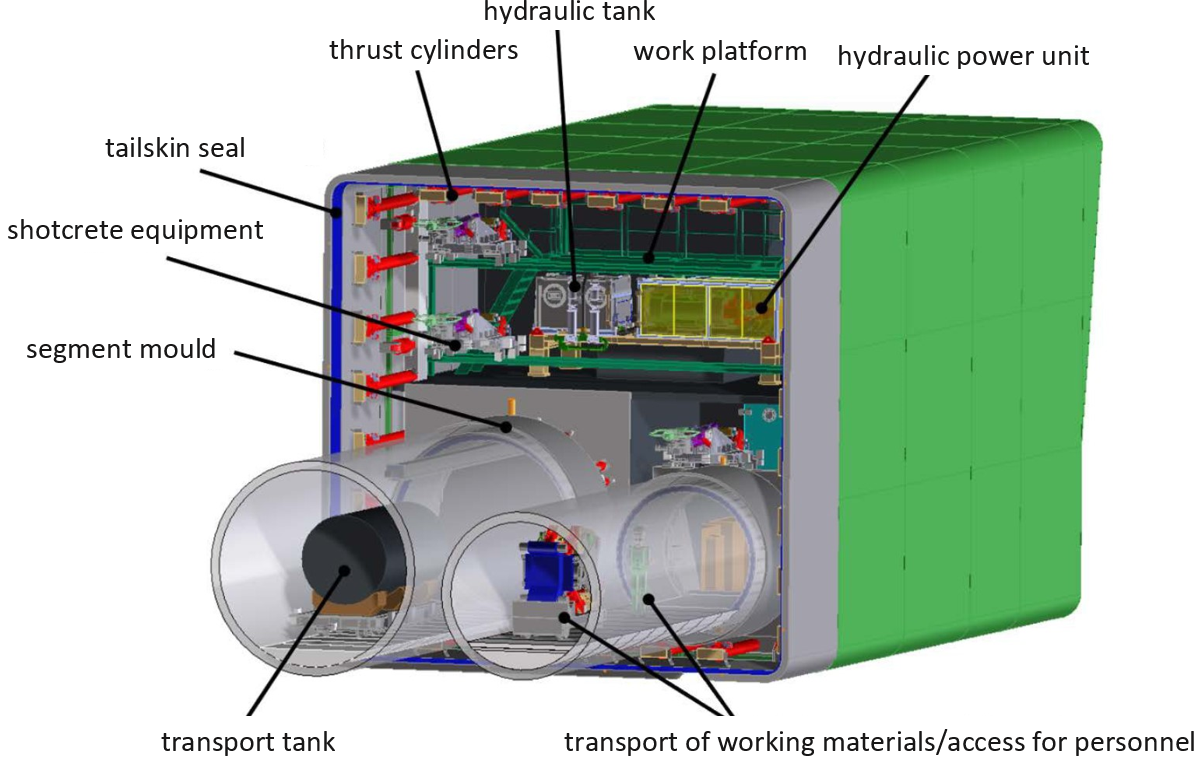

In the ‚Study on the Suitability and Development Needs of Equipment and Tools for Use in the Asse II Mine‘ in 2015, shield tunnelling with partial face excavation was already examined as a possible retrieval method. Shield machines are normally used in mechanised tunnel construction and are characterised by the fact that the entire processes take place in the protection of an enveloping shield. In Figs. 3-5, the shield is shown in green, while the rear part of the shield, the so-called tailskin, is shown in grey. Partial face excavation in particular is used for very easily detachable rock in stable rock, short heading lengths and non-circular cross-sections. One advantage of partial face excavation is the good accessibility to the tunnel face. The tunnel face describes the material in front of the excavation tools of the machine and is located on the left in Figs. 3 and 4. This accessibility is required when there is a high probability of encountering obstacles. [3]

It can be seen in the site plan of Fig. 2, the emplacement chambers of the chamber groups ‚South‘ and ‚East‘ are located next to each other along a curve on the 750-m-level. For this reason, five parallel tunnelling routes were prioritised in the concept ‚Shield tunnelling with partial face excavation‘, which encompasses the different widths of the emplacement chambers and the pillars in between in their total width and run along this curve in their length. Five partial-face excavation machines can drive up the drifts with a time delay over different distances from east to west and completely clear the similarly high emplacement chambers by taking into account an overprofile. The overprofile is necessary to completely cover and remove the damaged and possibly contaminated inner sides of the emplacement chambers. Assembly and disassembly caverns must be constructed at the beginning and end of each driveway.

Fig. 2: Ground plan of the construction method in relation to the emplacement chambers of the 750-m-level [2]

A partial-face excavation machine therefore alternately passes the pillars between the emplacement chambers, which are made of salt rock, and the contents of the emplacement chambers themselves. The contents of the emplacement chambers and their structure vary from chamber to chamber.

The waste packages were tipped as well as stacked horizontally or vertically, depending on the storage or discharge technique. Salt was blown, tipped or dumped to bed and shield the radioactive waste packages. Both partial and full backfills were produced with the crushed salt, also to stabilise the surrounding rock. Due to convergences as well as post-fractures of the surrounding salt rock, the solution influxes that occurred over the past decades and the resulting corrosion phenomena on the containers, the conditions within the emplacement chambers are unclear. The corroded casks themselves may also be deformed, burst as well as shattered, and it is assumed that there is a matrix of (possibly solidified) crushed salt around the casks. [2]

Partial-face excavation machine

At the tunnel face (left in Fig. 3) the salt rock of the pillars or the packages inside the emplacement chambers can be loosened and lifted with the help of the tools. A vacuum can be created between the tunnel face and the machine to prevent contamination from being carried into the interior of the machine via radioactive particles in the air. [2]

Fig. 3: Conveying route of the transport container from the tunnel face, to the excavation chamber and to the disposal tunnel [2]

The driving of the emplacement chambers and the pillars creates a cavity that has to be backfilled behind the machine. For this purpose, sorel concrete is placed both as shotcrete and as extruded concrete (see Fig. 5). In this way, the rock can be stabilised and at the same time a structure can be created on which the partial-face excavation machine can support itself for further travel. In this so-called ‚cavity filling‘ (see Fig. 4), two tunnel tubes are cut out for the period of retrieval. After suitable repacking for transport, the materials can be removed through the larger tunnel tube (disposal tunnel) (see fig. 3), the smaller tube serves as access for personnel and for the transport of working materials (passenger and utility tunnel). After successful retrieval and salvage of the partial-face excavation machines, the two tubes can be backfilled. Both the cavity filling and the backfilling of the tunnel tubes (transportations tunnels) are made of sorel concrete. [2] Sorel concrete has already been used for the production of flow barriers and various backfillings in the Asse II mine. The main components of sorel concrete are magnesium oxide as a binder and crushed salt as aggregate, which are mixed with magnesium chloride solution. [4]

Fig. 4: Rear view of the partial-face excavation machine with cavity filling [2]

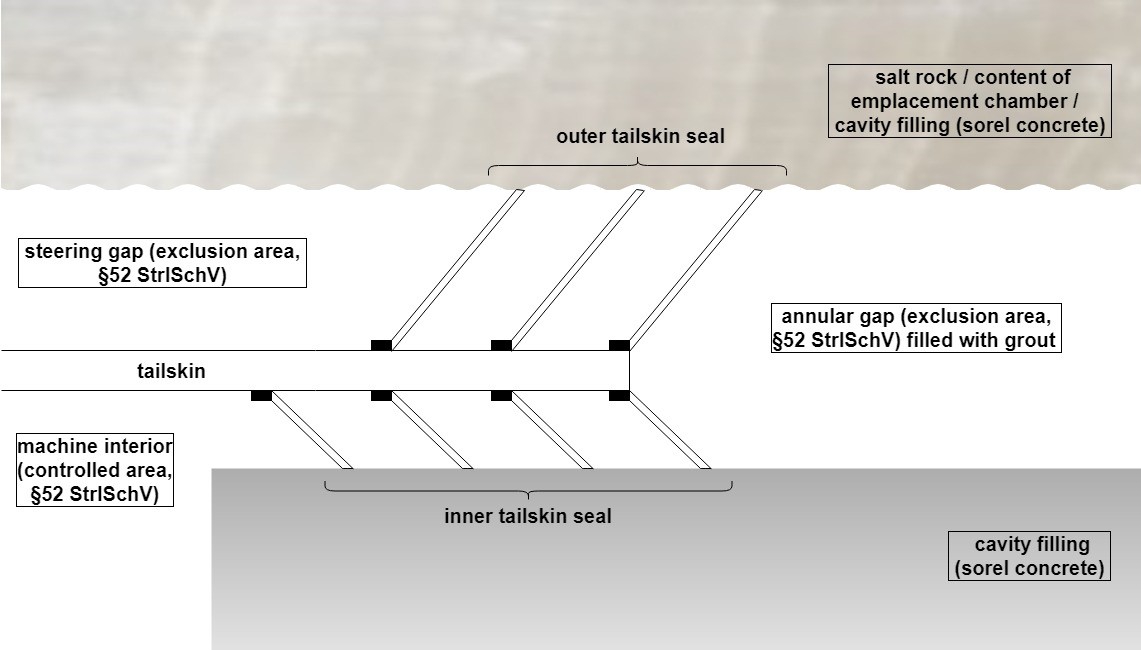

Once the tunnel face has been completed, the machine can support itself against the cavity filling by means of thrust cylinders and move forward. When advancing, the annular gap that becomes free behind the tailskin can be filled with grout immediately. At the end of the shield shell, an (inner) tailskin seal is provided, which seals the interior of the machine against the annular gap. [2] In figs. 3-5, the thrust cylinders in the rear part of the machine (tailskin) are shown in red, the tailskin seal in blue.

Fig. 5: Internals and machine equipment of the partial-face excavation machine, e.g. thrust cylinders and (inner) tailskin seal [2]

In the course of the in-depth investigations, an outer tailskin seal was added to the partial-face excavation machine designed in the study. This seals the steering gap against the annular gap, and prevents material from the annular gap from getting around the shield or up to the tunnel face (see Fig. 6). This ensures that the annular gap is filled conclusively under pressure. This is particularly important in the area of the pillars between the emplacement chambers, as this minimises contamination carry-over between the chambers and the barrier effect of the pillars can be maintained to the maximum.

Differentiated consideration of the tailskin seal

Due to the technical and legal framework conditions existing in a repository, it is necessary to mirror all components and systems of a shield machine against the resulting special requirements, to evaluate their applicability and functioning, and to make adjustments if necessary.

For the investigations of the two tailskin seals, a comprehensive catalogue was compiled in each case, in which various loads play an essential role. The mechanical loads on both seals are exceptionally high due to the square cross-sectional shape of the shield machine. This is intensified by damage in the roofs, which can lead to loosening on the shield skin of the machine, and thus also on tailskin seals. In addition, chemical stresses occur, mainly from the liquid sorel concrete and saturated sodium chloride solution. The influence of ionising radiation on the tailskin seals is considered negligible due to the low activity inventory.

Based on this catalogue, conventionally used tailskin seals were evaluated with regard to their suitability for shield tunnelling in the Asse II mine. Different aspects have to be given priority in the requirements for the respective tailskin seal. The inner tailskin seal must primarily fulfil a barrier effect towards the trailing annular gap, usually by building up a high pressure difference between the areas to be separated. The reason for this is the classification of radiation protection areas according to §52 of the Radiation Protection Ordinance (German: Strahlenschutzverordnung = StrlSchV), which defines the annular gap as a ‚exclusion area‘, while the interior of the machine represents a ‚controlled area‘ (see Fig. 6). For the outer tailskin seal the focus is on high wear resistance to obstacles outside the machine.

Fig. 6: Schematic of an inner and outer tailskin seal in partial-face excavation machine with description of the steering gap and annular gap [own figure]

As a result of the investigations, an inner tailskin seal was first designed which combines various conventional design elements. The basis for this is a wire brush seal with external spring plates and three sealing chambers, which is modified with a lubricant compression line and enlarged sealing chambers. With the help of the pressurised tail seal compound, this can meet the high demands on the barrier effect. In addition, the spring plates at the rear of the annular gap, in combination with the lubricant used, make it easier to start up the machine, as brushes in contact with the liquid backfilling (grout inside the annular gap) would stick together and be damaged over time. The lubricant itself also protects against the aggressive chemical environment in the adjacent annular gap. The enlarged sealing chambers increase the protection of the sealing system with a kind of spring effect – both in case of post-fractures from the rock mass and in case of occurring convergences.

Subsequently, the outer tailskin seal was designed from three rows of spring plates, which are also modified with lubricant injection lines. The arrangement of three seal rows ensures sufficient redundancy, which is why the lubricant supply was also designed redundantly, so that the outermost seal row always has an associated supply line. In order to prevent the spring plates from being torn off by obstacles – such as barrel bundles from the emplacement chambers or rock fragments from the surrounding salt rock – their bearing was embedded in the shield casing and thus protected. The number of seals in a row also ensures a certain redundancy here.

Conclusion

Within the scope of the investigations, comprehensive findings were obtained for the problems occurring during shield tunnelling in the Asse II mine. So far, not all components have been investigated in a differentiated manner.

In further investigations, for example, aspects such as the interactions between the shield machine and the surrounding salt rock or the synergies and disadvantages of the parallel tunnel routes could be determined. It has been shown that the various situations of the partial-face excavation machine with changing framings – such as salt rock, already hardened sorel concrete from preceding machines or contents of the emplacement chambers – represent a special challenge. Especially when feeding from cavity filling, the stability of the lateral walls along the travel distances plays an important role. Against this background, for example, the sequence of the partial-face excavation machines would have to be adjusted so that the first machine starts in the direction of travel on the left in order to be able to support itself against the salt rock in the south – especially in the area of the emplacement chambers (see Fig. 2). The grouting (of the annular gap) in the area of the emplacement chambers could also be considered in more in-depth investigations. A further aspect would be the compatibility of the tunnelling concept with the emergency planning for a possible flooding of the Asse mine. At present, the reduced barrier effect of the drilled-through pillars between the emplacement chambers as well as the volume of the five shield machines and their underground infrastructure represent significant disadvantages of shield tunnelling with partial-face excavation.

The retrieval of radioactive waste from the Asse II mine is scheduled to begin in 2033, in this sense: Glück auf!

References

[1] Plan zur Rückholung der radioaktiven Abfälle aus der Schachtanlage Asse II – Rückholplan, Verfasser: Bundesgesellschaft für Endlagerung mbH Peine/Remlingen, Stand: 19.02.2020

[2] Machbarkeitsstudie für die Methode „Schildvortrieb mit Teilflächenabbau“ – Studie zur Eignungsfähigkeit und zum Entwicklungsbedarf von Gerätschaften/ Werkzeugen für den Einsatz in der Schachtanlage Asse II, Herrenknecht AG im Auftrag des Karlsruher Instituts für Technologie (KIT), Technologie und Management des Rückbaus kerntechnischer Anlagen (TMRK), Schwanau, Karlsruhe; Stand: 13.05.2015

[3] Maidl, B., Herrenknecht, M., Maidl, U., Wehrmeyer, G. 2011. Maschineller Tunnelbau im Schildvortrieb. Ernst & Sohn

[4] Schachtanlage Asse II: Nachweis der Langzeitbeständigkeit für den Sorelbaustoff der Rezeptur A1; ERCOSPLAN, TU BAF (IFAC), IFG; Stand: 10.08.2018

![Fig. 1: Emplacement chambers on different levels in the mine workings of the Asse II mine [1]](https://atw-scientific.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/Abbildung-1_eng.png)

![Fig. 2: Ground plan of the construction method in relation to the emplacement chambers of the 750-m-level [2]](https://atw-scientific.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/Abbildung-2_eng.png)

![Fig. 3: Conveying route of the transport container from the tunnel face, to the excavation chamber and to the disposal tunnel [2]](https://atw-scientific.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/Abbildung-3_eng.png)

![Fig. 4: Rear view of the partial-face excavation machine with cavity filling [2]](https://atw-scientific.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/Abbildung-4_eng.png)

![Fig. 5: Internals and machine equipment of the partial-face excavation machine, e.g. thrust cylinders and (inner) tailskin seal [2]](https://atw-scientific.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/Abbildung-5_eng.png)

![Fig. 6: Schematic of an inner and outer tailskin seal in partial-face excavation machine with description of the steering gap and annular gap [own figure]](https://atw-scientific.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/Abbildung-6_eng.jpg)

0 Comments