BumSoo Youn

Senior Researcher

Nuclear Safety Analysis Group

–

International Trends & Developments in Nuclear

Central Research Institute, Korea Hydro and Nuclear Power Co., LTD., Republic of Korea

bsyoun81@khnp.co.kr

Article

–

–

–

–

Improving Henry-Fauske Critical Flow Model in SPACE Code and Analysis of LOFT L9-3

Introduction

The SPACE code offers several options for critical flow model. One of the option is Henry/Fauske – Moody model. When using this model, Henry-Fauske critical flow model is used for single phase liquid and Moody model is used for 2-phase flow. For Henry-Fauske model, SPACE code assumes non-equilibrium(NE) factor of 0.14. In previous OPR1000 SBLOCA analysis methodology based on RELAP5 code, non-equilibrium factor of 1.0 was used to get more conservative break flow. To develop SBLOCA analysis methodology for OPR1000 using SPACE code, it was necessary to use different non-equilibrium factor from SPACE default values for Henry-Fauske model. The SPACE code was improved by adding additional option for Henry/Moody – Moody model, which uses user input non-equilibrium factor. To accept user input equilibrium factor, the SPACE code is improved by expanding lookup table used in Henry/Fauske – Moody model. To verify the new model, we perform verification calculations on LOFT L9-3 which is a representative integral effect test(IET).

Experimental evaluation

Henry-Fauske critical model applied to existing SPACE codes(NE=0.14) will predict lower critical flow rates over the period of transition from subcooled liquid to two-phase fluid compared to RELAP5 critical flow models assuming a non-equilibrium(NE) factor of 1.0.

Overview of LOFT L9-3 Experiments

The LOFT L9-3[1] experimental purpose is to provide experimental data to developers of analysis codes for ATWS analysis, evaluate alternative methods of reaching long-term shutdown without inserting control rods after ATWS, and verify the applicability of point kinetics model or transients. In addition, the experimental data provided is used to determine the behavior characteristics of the primary system due to loss of main feedwater flow rate on the secondary side of the steam generator and to determine the two-phase and overcooling flow characteristics released through PORV and SRV at high pressure.

The LOFT L9-3 experimental device is a 50MWt pressurized light water reactor designed at a scale of 1/60 based on a 4-Loop Westinghouse-type nuclear power plant.

As shown in Fig. 1. it consists of five main components and subsystems, including the reactor core, primary coolant system, blowdown mitigation system, emergency core cooling system, and secondary cooling system. The blowdown mitigation system consists of a pump and steam generator simulation device, a Quick-opening discharge valve that simulates a break, and a tank that collects coolant released through a break simulation valve.

The reactor core of the LOFT L9-3 experimental device is approximately 1/2 length(1.68m) of the commercial reactor core, and the square core group contains 21 guide tubes out of 225 rod positions(15×15).

Figure 1. LOFT Facility Schematic.

Experimental Conditions

The LOFT L9-3 experimental conditions begin at normal conditions, such as core power of 48.7MWt, cold leg temperature of 557.0K, hot leg temperature of 576.4K, pressurizer pressure of 14.98MP, and steam generator pressure of 5.61MPa. The key steady-state initial conditions of the experiment are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Initial value of experiment

Parameter | Experiment | SPACE |

Mass flow rate(kg/s) | 467.6 | 467.63 |

Hot leg pressure(MPa) | 14.98 | 14.95 |

Cold leg temperature(K) | 557.0 | 555.04 |

Hot leg temperature(K) | 576.4 | 574.56 |

Power level(MWt) | 48.7 | 48.7 |

PZR Liquid temperature(K) | 615.2 | 614.78 |

PZR Pressure(MPa) | 14.98 | 14.98 |

SG Liquid level(m) | 3.15 | 3.19 |

SG Pressure(MPa) | 5.61 | 5.55 |

SG Mass flow rate(kg/s) | 25.7 | 25.6 |

LOFT L9-3 SPACE Modeling

SPACE modeling is shown in Fig. 2. SPACE code input from LOFT L9-3 experiments was written with reference to NUREG/IA-0192[2]. The reactor pressure vessel was divided to simulate the upper and lower cavities of the core bypass flow, and the core was modeled as a non-fuel part in the upper and lower part and a fuel part represented by three vertical nodes.

The steam generator was modeled by dividing it into 12 volumes for U-tube and 19 volumes for secondary. The main feedwater model was modeled using TFBC Component, especially the main feedwater and steam flow parts, using control logic to maintain constant pressure on the secondary side.

The pressurizer was modeled with nine volumes using the SPACE code pressurizer model, and the surge line under the pressurizer is connected to cell C110 and the pressurizer spray system is modeled with TFBC Component C407 and C406. In particular, in the case of spray system, the spray system is operated using the trip signal so that fluid from cold leg(C150) enters the pressurizer through TFBC Component C407.

In the evaluation of LOFT L9-3 experiments using SPACE code, the normal state was verified using null transients, and then the transient state was simulated using the Restart file and the results were evaluated.

Figure 2. LOFT L9-3 Facility Nodalization for SPACE Code Verification.

LOFT L9-3 Evaluation Results

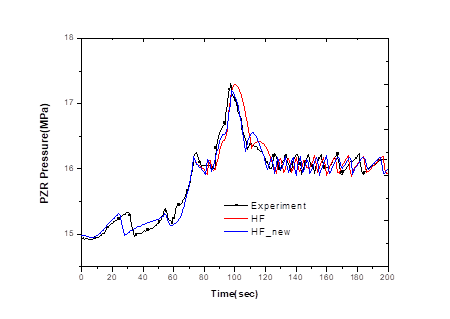

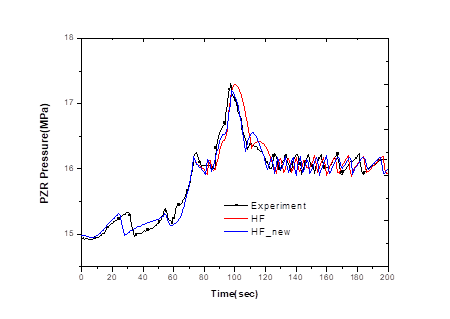

Fig. 3. shows the pressure change of the pressurizer. According to the experimental values in the figure, the pressure of the system gradually increases as the main feed water supplied to the steam generator is initially closed and the heat transfer from the primary to the secondary side of the steam generator decreases. The pressurizer pressure increases and reaches the setting of the pressurizer spray system. When the setting is reached, the pressurizer spray system is activated and the pressurizer pressure is reduced at 31 seconds. The continuous decrease in heat transfer to the steam generator causes the pressure to rise again. The pressure of the pressurizer is increased further as the steam generator MSCV closes at 67.3 seconds. The pressurizer pressure then reaches the opening setting of the PORV and decreases when the PORV is opened at 73.8 seconds. However, due to the absence of a replenishment of the main feedwater of the steam generator, the pressure rises again and the SRV setting of the pressurizer is reached at 96.8 seconds. The pressurizer pressure reaches the maximum pressure value at 97.5 seconds and then decrease. After 120 seconds, the pressurizer PORV and SRV repeat open and close, causing the pressure to repeat rise and fall within a small range.

The SPACE predictions also show similar results to the experimental results. Initially, the main feedwater to the steam generator is interrupted, causing the pressurizer pressure to rise just like the experiment. The pressure that was decreasing due to the operation of the pressurizer spray system gradually increases again after the spray system stops. The increased pressure is reduced again in 55 seconds by the operation of the spray system. The MSCV of the steam generator closes at 67.3 seconds, resulting in a rapid increase in pressure as shown in the experimental results. The pressure then reaches the open setting of the pressurizer PORV, which opened at 73.8 seconds, but continue to rise, somewhat different from the experimental value trend. The rising pressure decreases at 90 seconds, but without the complement of the steam generator’s main feedwater, the pressure rises again and reaches a maximum pressure slightly higher than the experimental results at 103 seconds. Subsequently, the pressure s reduced due to the operation of the PORV, SRV, and pressurizer spray systems of the steam generator, and after 120 seconds, the rise and fall are repeated near 15.5MPa to 16MPa.

The new Henry-Fauske critical flow model shows more similar results to experimental results than existing models.

Figure 3. Pressure change of the pressurizer

Fig. 4. shows the change in the pressure of the steam generator. According to the results of the experiment, the pressure of the steam generator will gradually increase as the main feedwater of the steam generator is closed. As the level of the steam generator gradually decreases, and steam generator U-tubes become uncovered heat transfer area decreases, and the pressure that was gradually rising decreases rapidly. The pressure then rises as MSCV closes. The rising pressure of the steam generator has slowed from about 100 seconds, when the PORV and SRV discharge flow of the pressurizer were maximum, and has since remained at a constant pressure(6.48MPa) while maintaining a slightly higher pressure than the initial value.

As the main feedwater of the steam generator is stopped, the SPACE result is also a graual increase in pressure, as is the result of the experiment. Gradually rising pressure peaks at 50 seconds and decreases with a slope similar to the experimental value. However, with MSCV closing at 673 seconds, the SPACE code prediction rises sharply from the experimental value after approximately 70 seconds. The rising pressure of the steam generator tends to be similar to the experimental value after about 130 seconds and maintains a constant pressure.

Figure 4. Pressure change of the steam generator

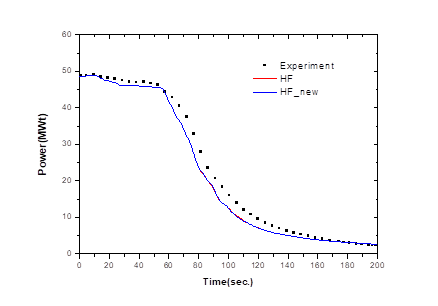

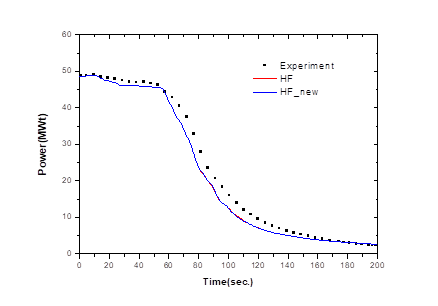

Fig. 5. shows the changes core power. According to the experimental results, if the main feedwater of the steam generator is closed, the primary system heat removal is lost and the temperature and pressure of the primary coolant are increased. As the temperature of the coolant cooling the core increases, the core power decreases gradually due to the feedback effect of the moderator. At 67.3 seconds, when the MSCV of the steam generator is closed, the core power is also rapidly reduced.

The SPACE code predictions tend to decrease somewhat faster than the experimental value between 70 and 160 seconds, but the overall trend is the same, and after 160 seconds, they are almost the same.

Figure 5. Core power change

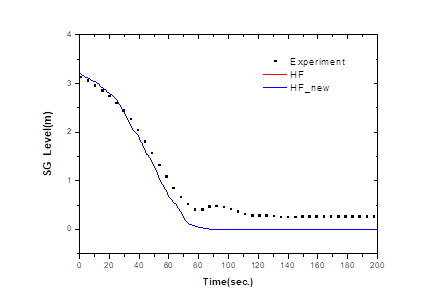

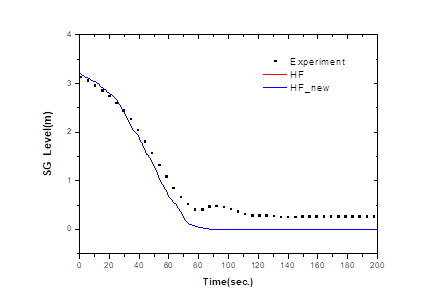

Fig. 6. shows the change in water level on the secondary side of the steam generator. According to the results of the experiment, the water on the secondary side of the steam generator will be reduced due to heat transfer with the primary side as the main feedwater of the steam generator is closed. The water level, which had been continuously decreasing at the same time as the main feed water closed, will not completely depleted after 120 seconds, and will gradually stabilize at about 0.2m high and remain constant.

The overall trend predicted by the SPACE code is similar to the experimental results. However, the results of the SPACE code begin to decrease in water level and are almost depleted by approximately 85 seconds. After that, it remains completely depleted and in a normal condition.

Figure 6. Steam generator water level change

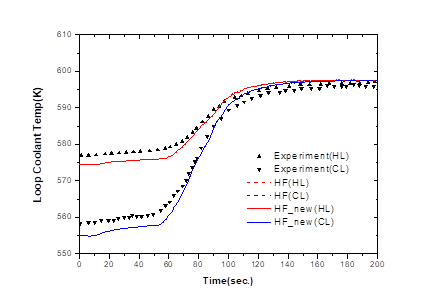

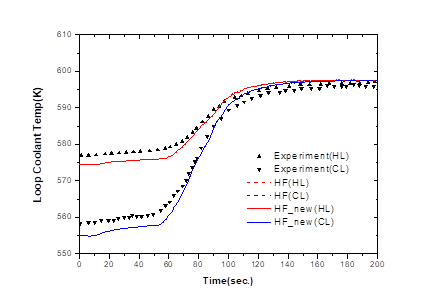

Fig. 7. shows the temperature of the coolant due to transient conditions. Experimental results show that the temperature of the coolant is slowly increasing as the main feedwater is closed. The increasing temperature of the coolant rises rapidly after 60 seconds due to the continued loss of the heat sink, and then the MSCV of the steam generator closes at 67.3 seconds, which increases the temperature even more rapidly. After 100 seconds, when the pressurizer pressure is at its peak, the pressure increase is slowed due to the operation of SRV and PORV of the pressurizer, and thus the temperature increase is slowed. As the pressure of the system is maintained constant, the temperature of the coolant is maintained constant.

As previously shown in Table 1, the steady-state temperature conditions using the SPACE code represent values about 2K lower than the experimental conditions, so there is a slight difference from the experiment at the beginning of the transient results. Although there is a difference at the starting point, the result of SPACE code also gradually increases the temperature as the steam generator main feedwater is stopped. As in the experiment, the temperature rises rapidly after 60 seconds, and remains constant after 100 seconds.

Figure 7. Coolant temperature change

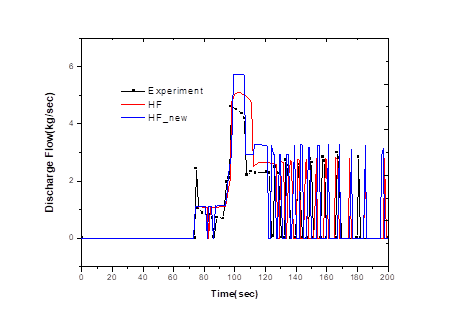

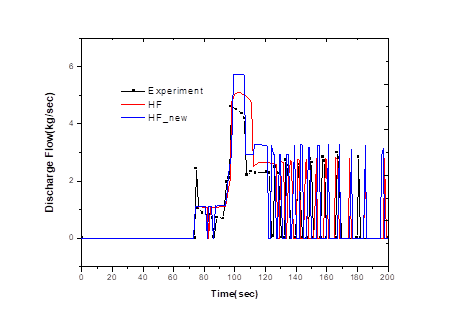

Fig. 8. shows the discharge flow rate through PORV and SRV during the transient. The main feedwater stops, the pressure gradually rises, and after 67.3 seconds the MSCV of the steam generator closes, reaching the opening set point of the PORV. At 100 seconds when the pressurizer pressure reaches its maximum, the discharge flow rate is maximum, and after that, the PORV and SRV are repeatedly opened and closed.

We compare the results with the existing Henry-Fauske critical flow model using the newly added Henry-Fauske critical flow model in the simulation with SPACE code for discharge of coolant through the PORV and the SRV. Overall, the opening points are similar, but there are some differences in the amount of discharge. When using the newly added Henry-Fauske critical flow model, we can confirm that the maximum discharge flow rate is higher and conservatively predicted.

Figure 8. Discharge flow rate

Conclusions

A new Henry/Fauske – Moody critical flow model option was added to the SPACE code. The SPACE code is improved by expanding lookup table used in Henry/Fauske – Moody model. For validation of improved model, LOFT L9-3 integral effect test is analyzed. The new model show better agreement with the experiment results. The new critical flow model will be used in the development of SBLOCA analysis methodology of OPR1000-type and WH 3-loop type nuclear power plants.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the Korea Hydro & Nuclear Power(KHNP) (A19LP05, Establishment of optimal evaluation system for safety analysis of OPR1000and Westinghouse type nuclear power plant(1)).

REFERENCES

- NUREG/CR-3427 ‘Experiment Analysis and Summary Report for LOFT ATWS Experiments L9-3 and L9-4’.

- NUREG/IA-0192 ‘Assessment of RELAP5/MOD3.2.2 Gamma with the LOFT L9-3 Experiment Simulating an Anticipated Transient without Scram’.

0 Comments