Antonio Ballesteros Avila

Scientific Officer

–

Operation and New Build

Joint Research Centre of European Commission, Petten, The Netherlands

Article

–

–

–

–

Operating Experience from Ageing Events Occurred at Nuclear Power Plants

Introduction

Nuclear safety of the operating nuclear power plants (NPP) has to be in the core of their life management. NPPs have to be operated safely and reliably. European countries involved in nuclear energy are spending their efforts in improving the safety of the operating plants and of those under construction, in accordance with the Euratom Treaty obligations [Euratom Treaty, 2012]. In this respect, the IAEA requirements for the safe operation of nuclear power plants identify, among others priorities, maintenance, testing, surveillance and inspection programmes and ageing management of safety related components [IAEA, 2018].

Recognising the importance of peer review mechanisms in delivering continuous improvement to nuclear safety, the amended Nuclear Safety Directive [European Union, 2014] introduced a European system of topical peer reviews (TPR). The subject “Ageing Management” was chosen in 2017 as the first TPR exercise on the basis of the age profile and the potential long term operation of European NPPs. The national assessment reports [ENSREG, 2018] prepared under this first TPR gave numerous examples where operating experience (OPEX) has been used to inform ageing management. There are many existing fora for sharing OPEX. For example, the International Reporting System (IRS) [IAEA, 2010] and the International Generic Lessons Learned Programme (IGALL) [IAEA, 2014] [IAEA, 2020] managed by the IAEA, the Committee on Nuclear Regulatory Activities (CNRA) and the Committee on the Safety of Nuclear Installations (CSNI) under the OECD-NEA, and the European Clearinghouse on Operating Experience Feedback of the Joint Research Centre (JRC) of the European Commission [JRC, 2021] [Ballesteros A., Peinador M., Heitsch M., 2015].

The original design life of structural, mechanical and electrical components, particularly those that technically limit the power plant operation (e.g. reactor pressure vessel, containment, etc.), was originally estimated to be around 30-40 years, considering anticipated operational conditions and ambient environment under which they are operated. In reality, the plant operational conditions and ambient environment parameters are below the limits established during the initial design. While economical feasibility falls into the operating organization competence, a decision regarding the plant safety level depends on country’s regulatory requirements. Generally, a thorough technical assessment of the plant physical condition is needed to identify safety enhancements or modifications, and the impact of changes to NPP programmes and procedures necessary for continued safe operation.

Many operators in Europe have expressed the intention to operate their nuclear power plants for longer than envisaged by their original design. From a nuclear safety point of view, continuing to operate a nuclear power plant requires two things: demonstrating and maintaining plant conformity to the applicable regulatory requirements; and enhancing plant safety as far as reasonably practicable. Depending on the model and age of the reactor, national regulators assume that granting long-term operation programmes will mean extending their lifetime by 10 to 20 years on average.

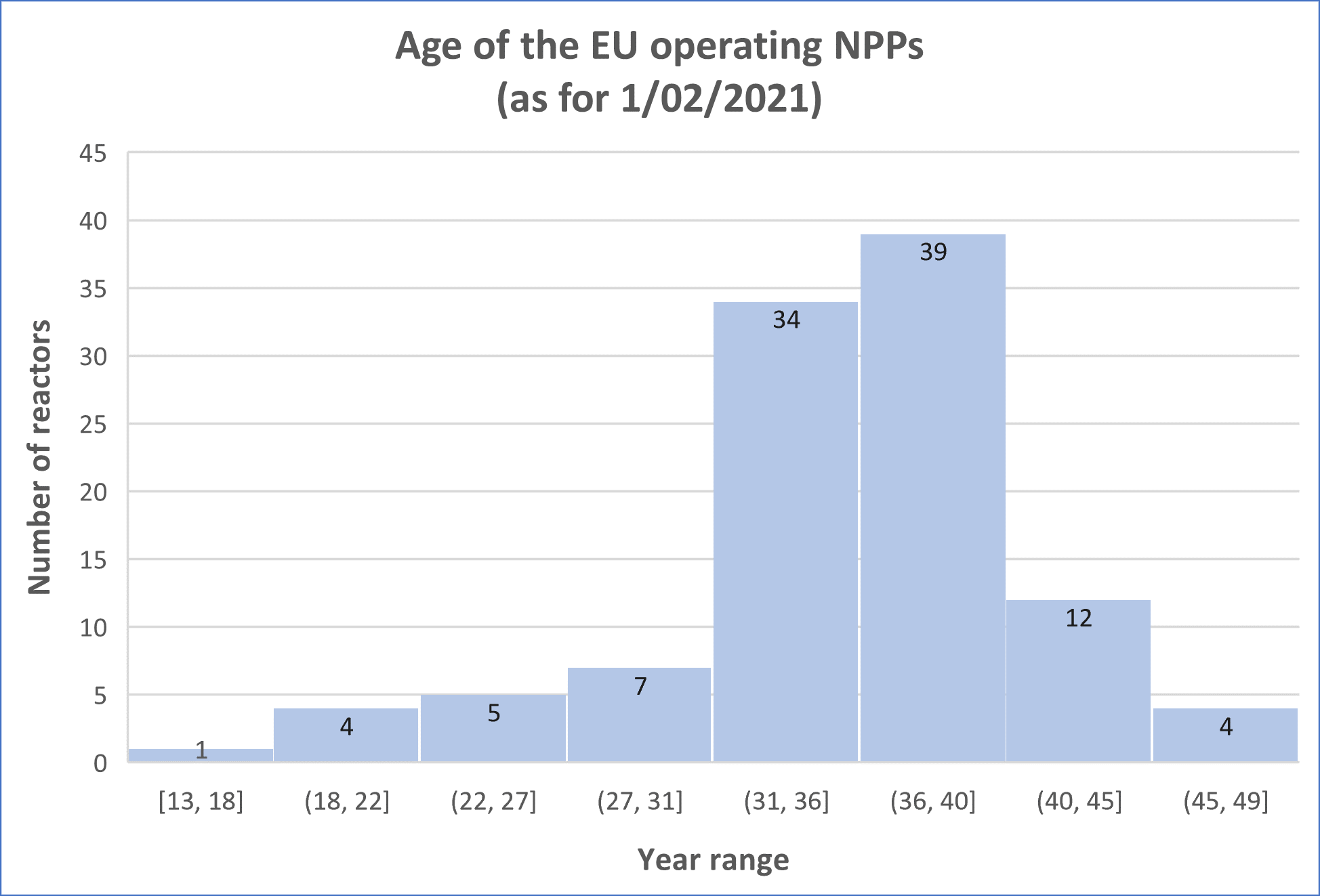

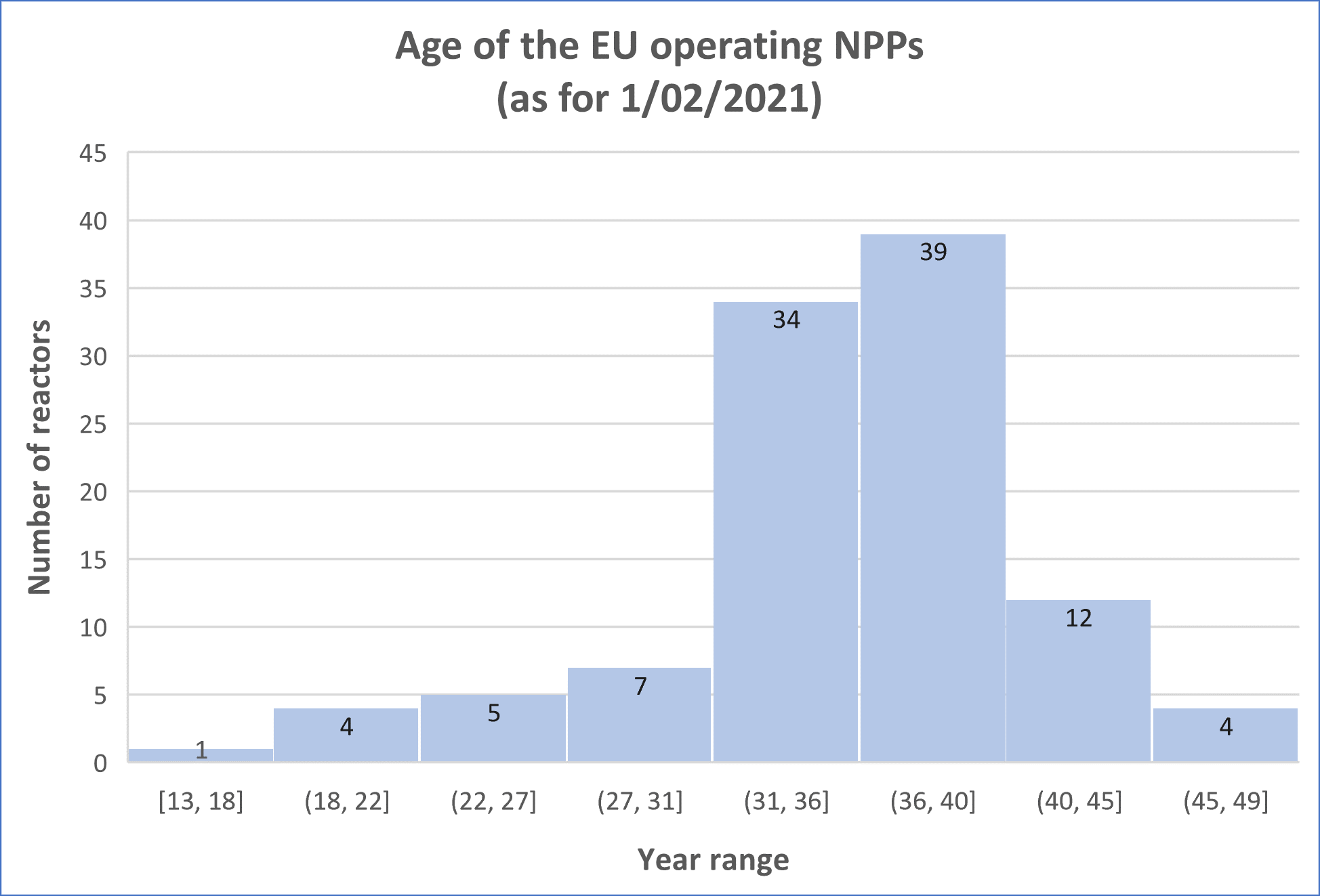

There are 106 nuclear power reactors in operation in the European Union (EU) in 13 of the 27 EU countries. The age distribution of current nuclear power plants is shown in Figure 1. A major part of the EU reactors are between 31 to 40 years old. Hence, from both the safety and security of supply viewpoints, ageing of these power plants is of increasing concern to European policy makers, citizens and utilities.

Figure 1: Age distribution of the EU operating nuclear power reactors

Methodology

The final objective of this work is to draw case-specific and generic lessons learned from ageing related events occurred at NPPs during a period of approximately 10 years. Namely, events reported between 01/01/2008 and 30/06/2018 in the IAEA IRS database. The IRS is an international database jointly operated by the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) and the Nuclear Energy Agency of the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD/NEA). The IRS was established as a simple and efficient system to exchange important lessons learned from operating experience gained in nuclear power plants of the IAEA and NEA Member States. The IRS database contains more than 4500 event reports with detailed descriptions and analyses of the event’s causes that may be relevant to other plants.

The screening of ageing related events was carried out in two steps:

- Step 1: The query capabilities of the IRS database are used to retrieve an initial list of potentially relevant events.

- Step 2: The reports obtained from the previous step are briefly reviewed to confirm their relevance. Even if apparently relevant, a report could be screened out if it is insufficiently detailed or if its quality is too low to be useful for the purposes of the study.

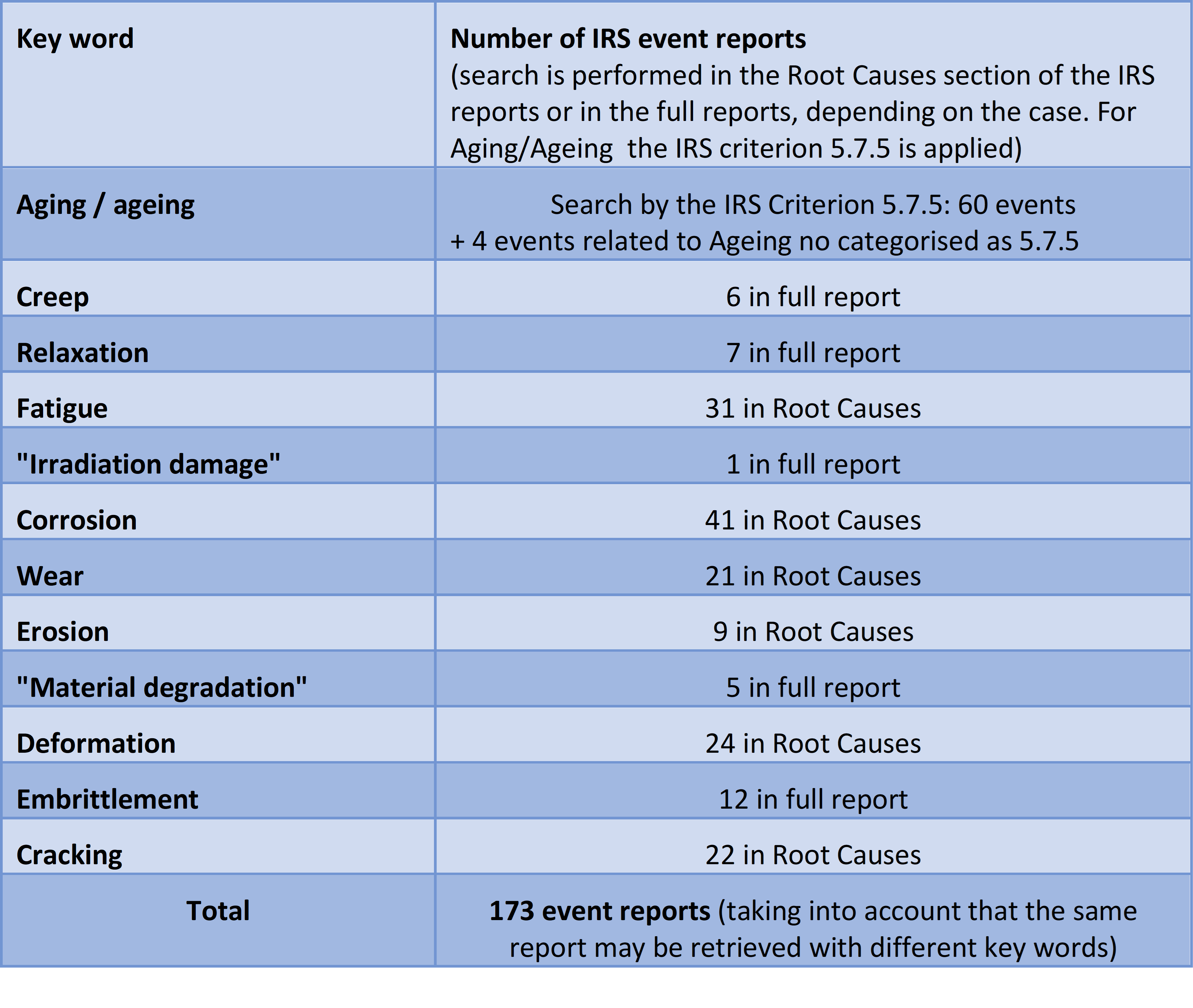

The query result in the IRS database for the period 01/01/2008 – 30/06/2018 was a list of 173 ageing event reports (step 1), which were reviewed to confirm their relevance. The querying results are summarized in Table 1, where the number of event reports is given together with the guide words used for the screening. IRS allows querying ageing events using the IRS code 5.7.5. But it was noted that some ageing events were not classified under this specific code. For that reason querying was also carried out by searching ageing events using different degradation mechanisms and their consequences.

After detailed analysis of the 173 event reports (step 2), only 113 reports were considered as relevant. All the reports were thoroughly reviewed in order to characterise the events. To facilitate this process, the events were classified according to the following criteria: plant status, the means of detection, the systems affected, the components affected, the direct cause, the root causes, the ageing mechanisms, the consequences and the corrective actions. Further to the classification of events, the reports are also reviewed to identify the aspects of the event that can be used as feedback from operating experience. These «low-level lessons learned» are attached to specific events, and generally can be understood only in the context of those events. For this reason, an effort has been done to define «high-level lessons learned», or simply «lessons learned» defined in such a way that they are not too specific (so that they are applicable only to one single plant) nor too wide (so that they can be considered as common sense, and already known to everybody).

Table 1 – Number of event reports in the IRS database

Analysis of events

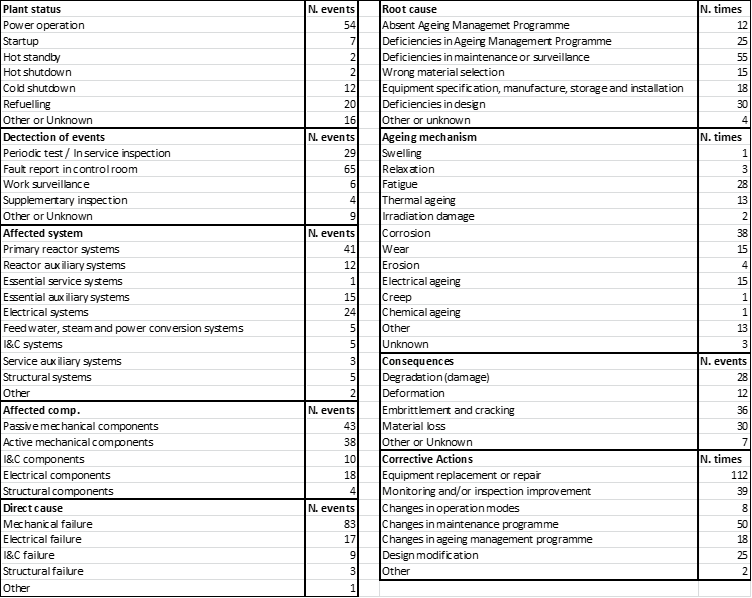

This section presents the result of the screening and classification process described above. The number of events for each family in a given category (plant status, detection, affected system, affected component, direct cause, root cause, ageing mechanism, consequences, corrective actions) is shown in Table 2.

It was interesting to calculate the average age of the nuclear power plant when the event occurred. This can be expressed by:

Average Age =

where,

n = final number of selected ageing events

t2 = time when the event happen

t1 = time when the plant started operation

The analysis provides an Average Age of 28 years (331 months) with a large standard deviation of 10 years (123 months) and a median of 30 years (357 months). In other words, on average, ageing related events occur after 28 years from the start of reactor operation.

Selected event reports have been characterised according to the criteria defined for this study: plant status, detection means, affected system, affected component, direct cause, root cause, ageing mechanism, consequences and corrective actions. The most relevant findings are highlighted below.

Table 2 – Number of events/times per family

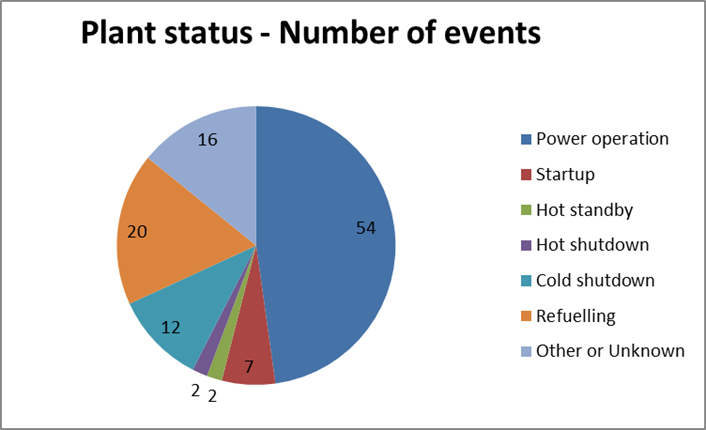

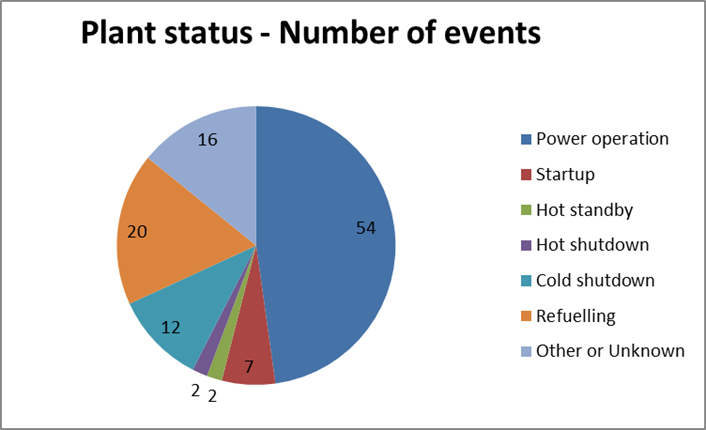

Plant status and detection means

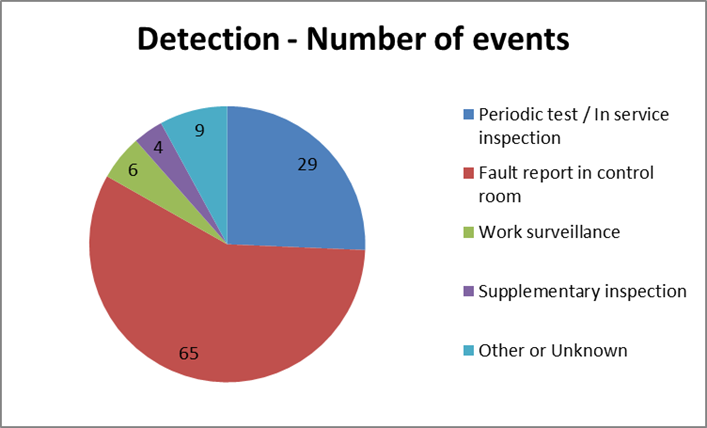

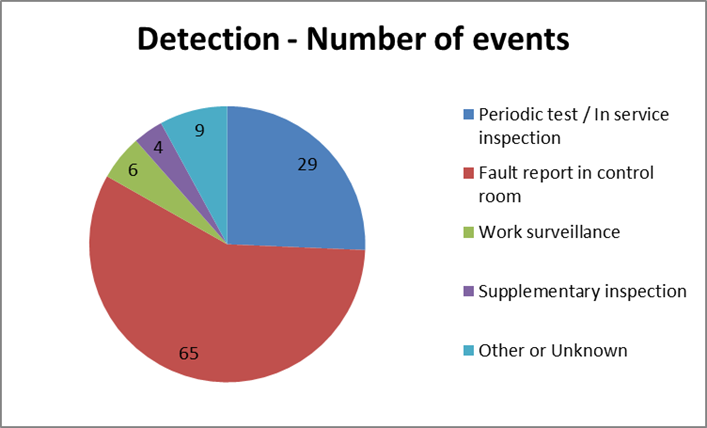

Figure 2 (up) shows the event distribution related to plant status. Nearly half of the events took place during power operation. Figure 2 (down) indicates that the major part of the events were detected by „fault report in control room“ (58%) followed by „periodic test / in-service inspection“ (26%). The fact that one of four ageing events were detected in periodic tests or in-service inspections highlights the importance of having sound inspection and maintenance programmes to avoid sudden failures during power operation with greater implications on nuclear safety.

Figure 2 – Plant status and detections means versus number of events

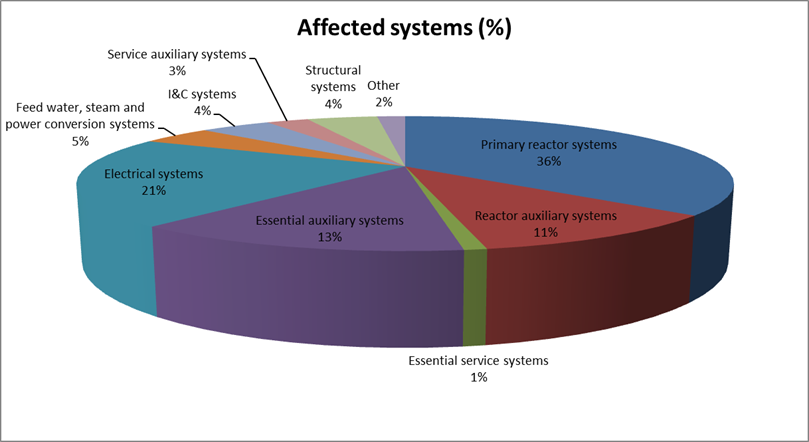

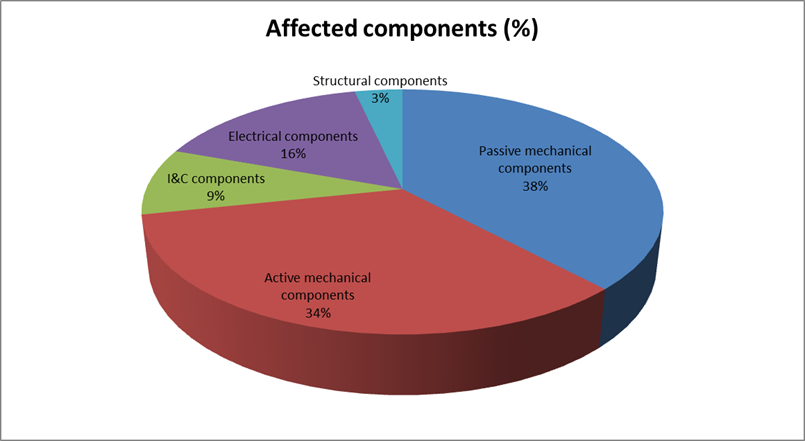

Systems and components affected

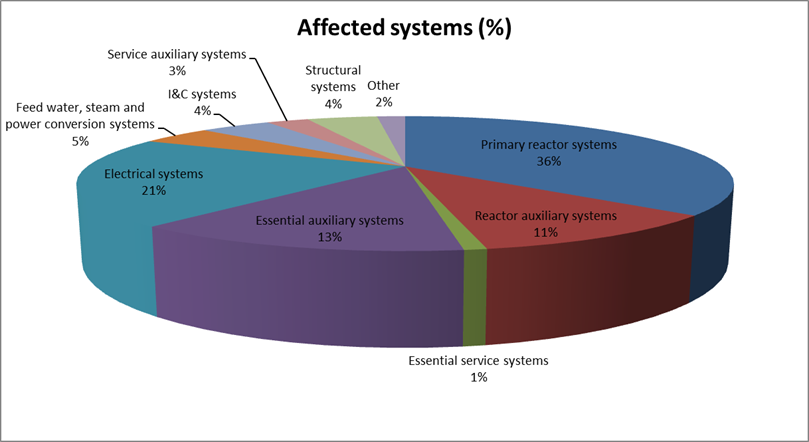

The distribution of events per system affected is presented in Figure 3. The largest percentage (36%) corresponds to the primary reactor systems, followed by electrical systems (21%) and essential auxiliary systems (13%).

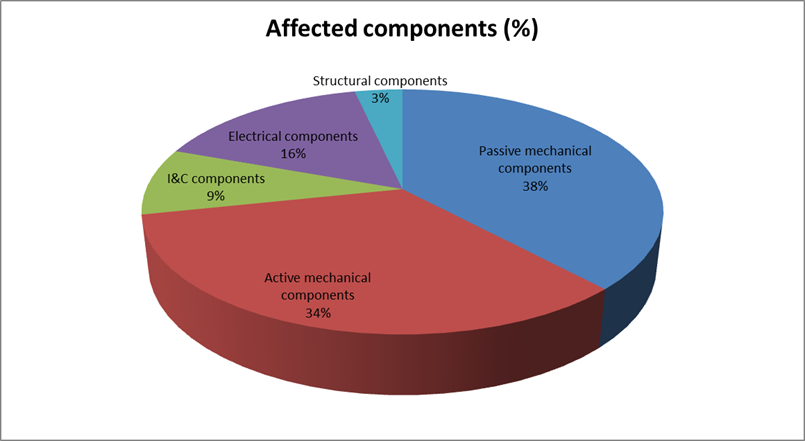

The distribution of events per component affected is given in Figure 4. Passive and active mechanical components are the most affected components (38% and 34%, respectively), followed by electrical (16%), I&C (9%) and structural components (3%).

Figure 3 – Number of events (%) per system affected

Figure 4 – Number of events per component affected

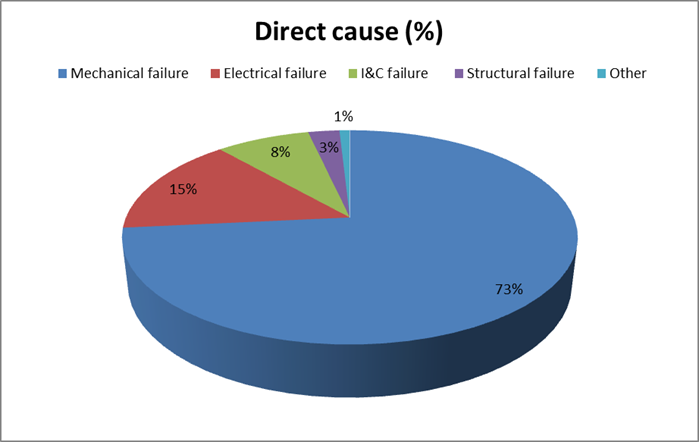

Direct and root causes

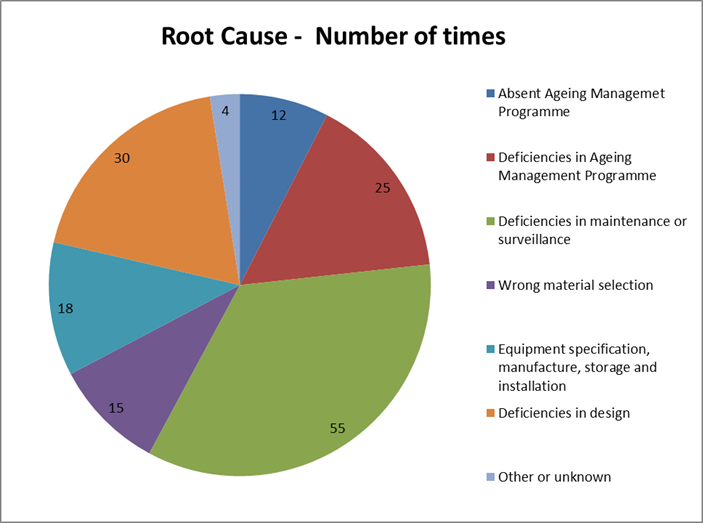

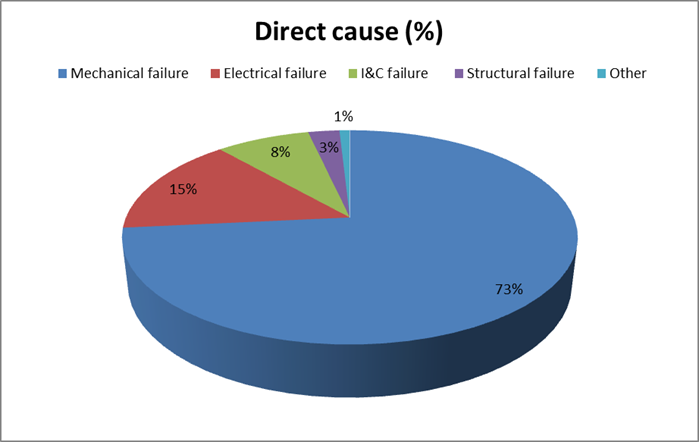

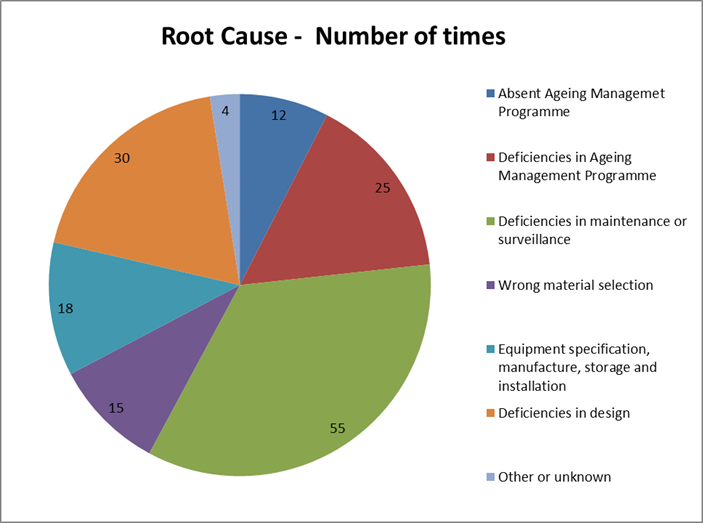

Figure 5 indicates that the main direct cause was mechanical failure. The distribution of root causes is given in Figure 6. A maximum of three different root causes was attributed to each event. Deficiencies in maintenance or surveillance is the most important root cause, followed by deficiencies in design and in ageing management programmes. To this respect, we infer that the establishment of an effective ageing management programme, as early as possible in the lifetime of the plant, will significantly contribute to preventing events and the resulting consequences.

Figure 5 – Number of events per direct cause

Figure 6 – Distribution of root causes

Ageing mechanisms

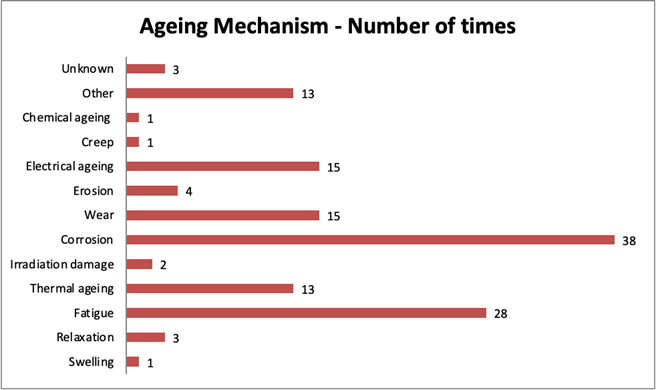

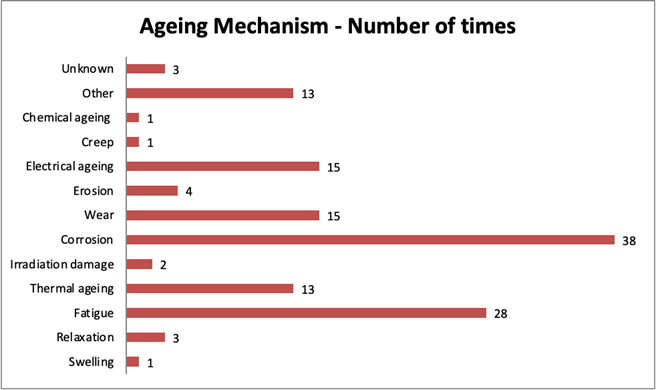

The category „ageing mechanism“ was split in 13 families, as indicated in Table 2, making it possible to allocate several (maximum three) ageing mechanisms to a single event. Figure 7 shows that corrosion (38 times) is the main cause of failure, followed by fatigue (28 times). Other important contributions are coming from thermal ageing, wear and electrical ageing.

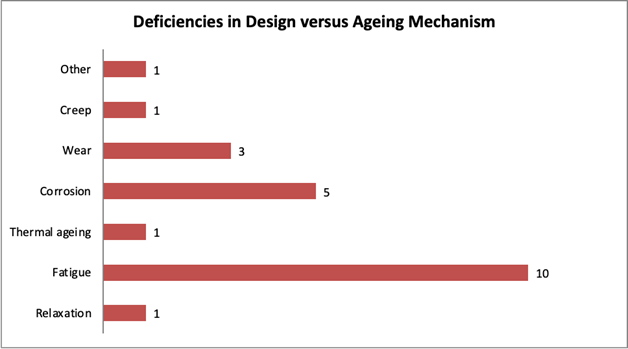

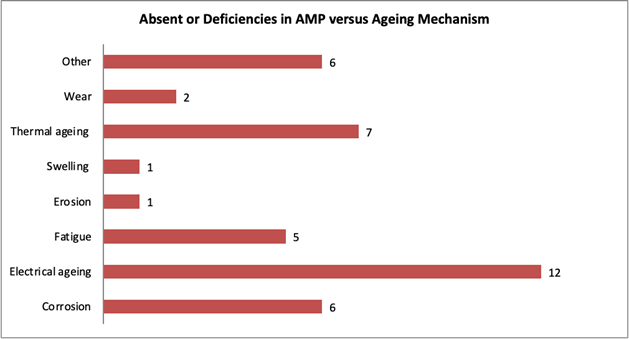

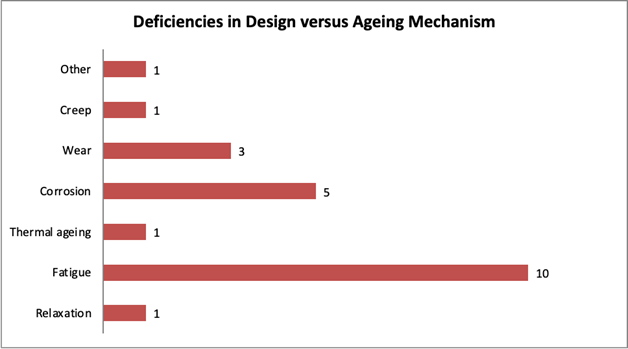

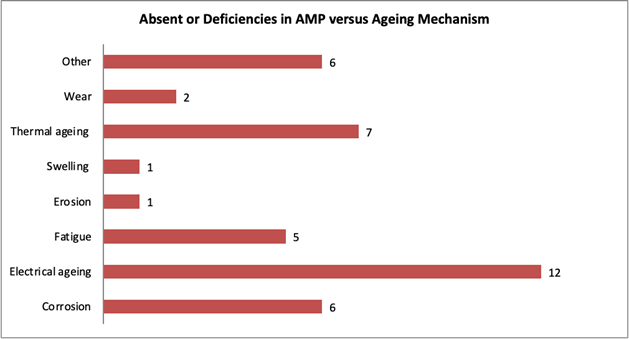

As it will be showed later in the section on lessons learned, many events only appear after long term operation of an aged component or material, and the main cause was a deficiency in design that was latent. Figure 8 put some light on this issue and illustrates that fatigue is the main degradation mechanism in relation to hidden deficiencies in design. Figure 9 correlates deficiencies (or absence) in ageing management programme with the ageing mechanism. In this case electrical ageing is the most relevant contributor to failure. This indicates the need for improvement of the ageing management programmes of electrical and I&C components.

Figure 7 – Ageing mechanisms present in the events

Figure 8 – Deficiencies in design versus ageing mechanism

Figure 9 – Deficiencies in ageing management programmes versus ageing mechanism

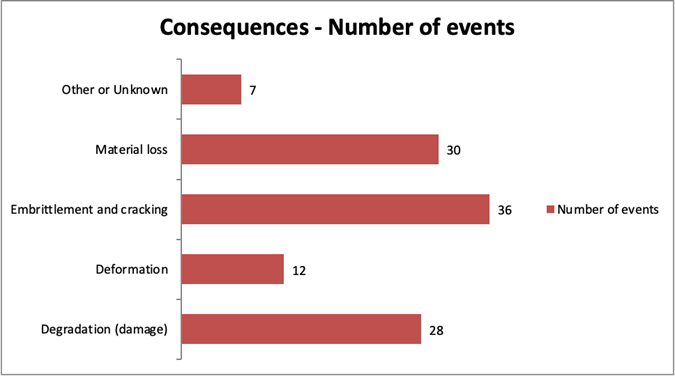

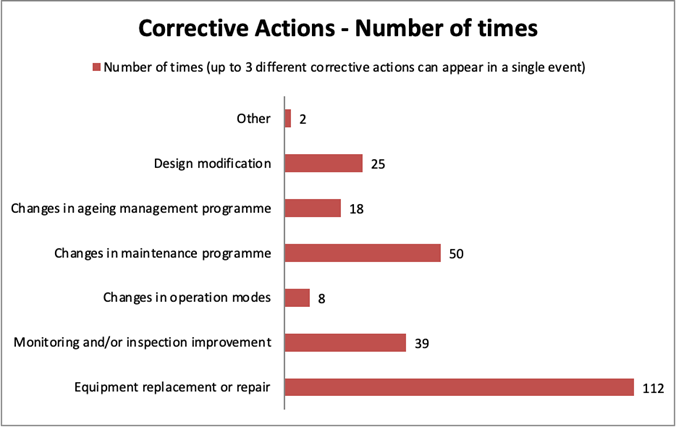

Consequences and corrective actions

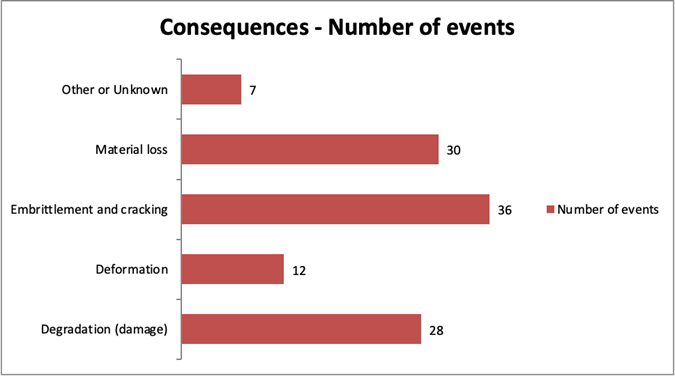

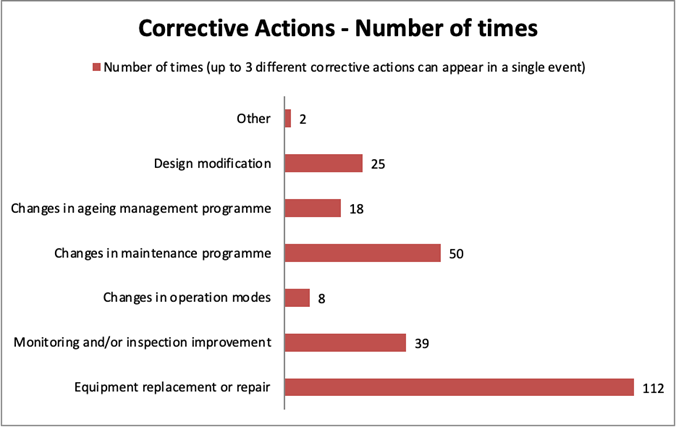

Figure 10 shows the distribution of events among different consequences. 36 events were related to embrittlement and cracking and 30 events to material loss (mainly due to corrosion).

Figure 11 illustrates the corrective actions. A maximum of three corrective actions were allocated to a single event. As expected, the main corrective action was the replacement or repair of equipment. Changes in maintenance programme was the second most usual corrective action followed, in this order, by monitoring or inspection improvement, design modification and changes in ageing management programme.

Figure 10 – Number of events per consequence

Figure 11 – Distribution of corrective actions

Lessons learned

The extraction of the lessons learned from the operating experience has been completed in two steps. First (step 1), low level lessons learned were retrieved from the IRS database, or developed in some cases, for a large number of the 113 analysed events. A total of 110 low level lessons learned were obtained. They are given, together with a short summary of the events, in Annex 2 of reference [Ballesteros Avila A., 2019]. Several lessons are allocated to the same event in many cases. These low level lessons learned are very specific, so that they would have a too limited applicability. To address this issue, the low level lessons learned were grouped under similar topic or underlying key message to get a high level lesson learned (step 2). In the following paragraphs the high level lessons learned are presented:

Lesson learned #1 – Appropriate measures should be taken and design features should be introduced in the design stage to facilitate effective ageing management throughout the life of the plant.

Lesson learned #2 – Ageing Management Programmes as well as maintenance programmes should be reviewed and updated to take into account modifications in the current licensing bases.

Lesson learned #3 – The monitoring of the environmental conditions, as information source for ageing management, is of high importance. In particular, a review of possible changes in environmental conditions (e.g. temperature, radiation, etc.) that could affect ageing should be performed in case of operational changes or structures, systems and components (SSC) modifications.

Lesson learned #4 – The maintenance and inspection programmes should be evaluated and, if considered necessary, updated (frequency, testing methods, procedures, etc.) on the basis of the findings of the ageing management programme.

Lesson learned #5 – Ageing management programmes for specific degradation mechanisms should be developed to avoid or mitigate accelerated ageing (e.g., flow accelerated corrosion, fretting, stress corrosion cracking, thermal ageing). It is important also to identify and justify possible associated changes in process conditions (e.g., flow pattern, velocity, vibration) that could cause premature ageing and failure.

Lesson learned #6 – The adequacy and effectiveness of the inspection and monitoring methods should be periodically reviewed to maintain plant safety and to ensure feedback and continuous improvements of ageing management. The evaluation of technology and methods should consider the need for detection of unexpected degradation, depending on how critical the SSC is to safety.

Lesson learned #7 – Adequate oversight by the licensee is recommended during all phases of design, procurement, testing, receipt inspection and installation to avoid events where wrong material is used. When a wrong or low performance material is already installed, the rate of material degradation can often be reduced by optimizing operating practices and system parameters.

Lesson learned #8 – Data on operating experience can be collected and retained for use as input for the management of plant ageing. Reviews of operating experience can identify areas where ageing management programmes can be enhanced or new programmes developed.

Lesson learned #9 – Earlier detection of degradation is necessary to ensure timely application of mitigation strategies. There is the possibility that such early physical damage (e.g., change of locally averaged material properties) can be detected with appropriate sensors.

Lesson learned #10 – The operating organization should ensure that ageing management programmes are reviewed on a regular basis and, if needed, modified to ensure that they will be effective for managing ageing. Where necessary, frequently as a result of reviewing operating experience, new ageing management programmes have to be developed.

Conclusions

Ageing is a concern for the safe long-term operation of NPPs. In particular for the EU nuclear reactors, many of them being between 31 – 40 years old. In this respect, operating experience from ageing events can contribute to a great extent to enhance nuclear safety.

The IRS database was screened to select relevant events related to ageing, which took place in the period 01.01.2008 – 30.06.2018. In total 113 events were analysed. The analysis showed that “28 years” represents the average age of a nuclear power plant when the event occurred. Deficiencies in maintenance or surveillance is the most important root cause, followed by deficiencies in design and in ageing management programmes. Corrosion is the main degradation mechanism, followed by fatigue. Other important contributions are coming from thermal ageing, wear and electrical ageing. Many events only appear after long-term operation of an aged component or material, and the main cause was a deficiency in design that was hidden.

110 low level lessons learned (specific for the events) and 10 high level lessons learned (generic) have been obtained in this study. They cover different areas, such as hidden deficiencies in design, the impact of ageing on maintenance and inspection, deficiencies or lack of ageing management programmes, use of wrong material, etc.

This study highlights that the continuous analysis of ageing related events and the efficient utilization of operational experience provides important insights for improving the quality of ageing management programmes and for preventing the occurrence of unusual events.

References

Ballesteros A., Peinador M., Heitsch M., 2015. EU Clearinghouse Activities on Operating Experience Feedback, BgNS Transactions volume 20 number 2 (2015) pp. 93–95.

http://bgns-transactions.org/Journals/20-2/vol.20-2_03.pdf

Ballesteros Avila A., 2019. Analysis of ageing related events occurred in nuclear power plants, Topical Study from the EU Clearinghouse on Operating Experience, Technical Report by the Joint Research Centre of the European Commission, JRC119082.

ENSREG, 2018. First Topical Peer Review Report „Ageing Management“, European Nuclear Safety Regulator’s Group ENSREG.

http://www.ensreg.eu/eu-topical-peer-review

Euratom Treaty, 2012. Consolidated version of the Treaty establishing the European Atomic Energy Community.

https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A12012A%2FTXT

European Union, 2014. Council Directive 2014/87/Euratom of 8 July 2014 amending Directive 2009/71/Euratom.

https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=uriserv%3AOJ.L_.2014.219.01.0042.01.ENG

IAEA, 2010. IRS Guidelines, Joint IAEA/NEA International Reporting System for Operating Experience, IAEA Services Series 19, Vienna.

https://www.iaea.org/publications/8405/irs-guidelines

IAEA, 2014. Approaches to Ageing Management for Nuclear Power Plants: International Generic Ageing Lessons Learned (IGALL) Final Report, IAEA-TECDOC-1736, IAEA, Vienna.

IAEA, 2018. Specific Safety Guide No. SSG-48, Ageing Management and Development of Programme for Long Term Operation of Nuclear Power Plants, IAEA Safety Standards, Vienna.

https://www.iaea.org/publications/12240/ageing-management-and-development-of-a-programme-for-long-term-operation-of-nuclear-power-plants

IAEA, 2020. Ageing Management for Nuclear Power Plants: International Generic Ageing Lessons Learned (IGALL), Safety Reports Series No. 82 (Rev. 1), IAEA, Vienna.

https://www.iaea.org/publications/13475/ageing-management-for-nuclear-power-plants-international-generic-ageing-lessons-learned-igall

JRC, 2021. European Clearinghouse on Operating Experience Feedback.

https://clearinghouse-oef.jrc.ec.europa.eu/

0 Comments