Young Jae Maeng

Chan Hyeong Kim

Professor

Hanyang University, Seoul, Korea

Decommissioning and Waste Management

Korea Reactor Integrity Surveillance Technology, Daejeon, Korea

–

Article

–

–

–

–

Error Reduction in Radioactivity Calculation for Retired Nuclear Power Plant Considering Detailed Plant-specific Operation History

Introduction

Of the more than 560 commercial nuclear power plants that are or have been in operation, approximately 120 plants have been permanently shut down and are in the process of decommissioning [1, 2]. In Korea, decommissioning of a retired NPP will begin in 2023; some countries have already decommissioned nuclear power plants. The schedule, strategy, and cost for reducing radioactive waste associated with decommissioning are closely related to the type and quantity of radioactive material present at the plant. Thus, evaluation of the radioactivity distribution of each radioactive isotope is important in sorting and disposal.

Radioactivity of structures near the reactor core including reactor internals, vessel, and concrete shield is mainly due to neutron irradiation, known as the neutron activation phenomenon which can be calculated after radiological characterization [3]. The radioactivity level is dependent on the neutron flux irradiating the structure and the neutron absorption cross-section of the materials.

The neutron flux level is generally dependent on the reactor power level and the cycle-specific fuel loading pattern. The power level varies during the plant lifetime through plant overhaul, emergency reactor trip, and low power operation such as heat-up, cool-down, and transient processes. Varying power levels affect the saturated activity value. For zero power operation including overhaul and reactor trip, the activities exponentially decrease based on the decay constant of each radioactive isotope. However calculating activities is difficult for a retired nuclear power plant due to long operation life and variable flux level. Thus, the calculation of radioactivity has been traditionally performed using average neutron flux and effective full power days [4, 5, 6, 7], which could result in significant error.

In the present study, a method for calculating radioactivity using detailed plant-specific operation history is introduced. The method considers cycle-specific neutron flux level and monthly operation history from the inception of the plant. The results of the calculated activities are compared with results of the traditional method and also compared with measurement data sets from five surveillance capsules from the plant.

Materials and methods

General activity calculation

The neutron-induced activation phenomenon is well known. The activity of the product nuclide when it is produced at a constant rate (atoms/s) due to neutron irradiation is written as [8]

where is activity (Bq), and is the decay constant (s-1) of the product nuclide. In Eq. (1), the constant production rate can be written as

where is the number of target nuclides irradiated by the neutron flux (neutrons/cm2-s), and (cm2) is the microscopic cross-section for the activation reaction. To calculate the activity manually, the integral term in Eq. (2) must be approximated in summation form as .

where is the number of target nuclides irradiated by the neutron flux (neutrons/cm2-s), and (cm2) is the microscopic cross-section for the activation reaction. To calculate the activity manually, the integral term in Eq. (2) must be approximated in summation form as .

If the target nuclide is irradiated by neutron irradiation for time (s) and undergoes decay for time (s), the activity becomes

where is the initial activity (Bq) indicating the production of activity according to Eq. (1) during time (s). Therefore, it is possible to calculate the activity including both irradiation period and decay period. Traditionally, this simple equation is used to estimate radioactivity distribution.

Activity calculation considering operation history and flux level

The method considering operation history and flux level is related to production rate represented by Eq. (2). If the neutron flux in Eq. (2) is changed, production rate also change. Assuming that the neutron flux is constant during a certain period, we can obtain in period as

where represents the last number of the group-wise neutron spectrum; 47 neutron energy group is applied in this study. is the group neutron spectrum during the period . The discretization through Eq. (4) allows manual calculation of activity. In Eq. (4), the neutron spectrum can be calculated as

where represents the last number of the group-wise neutron spectrum; 47 neutron energy group is applied in this study. is the group neutron spectrum during the period . The discretization through Eq. (4) allows manual calculation of activity. In Eq. (4), the neutron spectrum can be calculated as

where is the relative thermal power level of the period and is the group neutron spectrum corresponding to the full power level. In this study, cycle-specific values were calculated for each cycle using the RAPTOR-M3G neutron transport code [9] with the BUGLE-96 cross-section library [10].

where is the relative thermal power level of the period and is the group neutron spectrum corresponding to the full power level. In this study, cycle-specific values were calculated for each cycle using the RAPTOR-M3G neutron transport code [9] with the BUGLE-96 cross-section library [10].

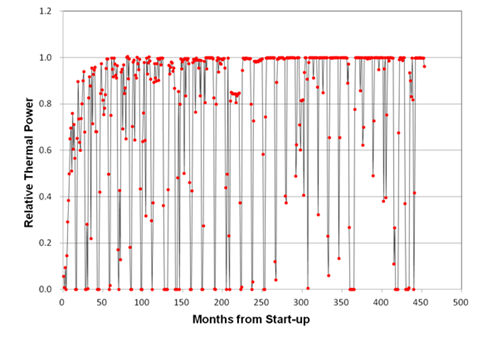

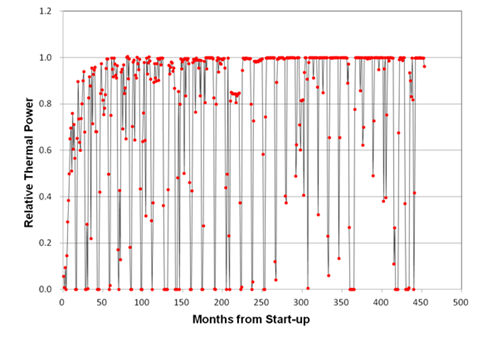

By applying relative thermal power level, we can consider two activation phenomena. First, the contribution ratios for low power operation periods can be considered comparing with full power operation. Thus, different saturated activity curves for each period can be considered even if the neutron flux level is constant in a fuel cycle. Second, it is also possible to reflect the decay for the periods of zero power. In this study, was considered monthly; the relative thermal power distribution over the plant lifetime is shown in (Figure 1).

If the final activity considering operation history and flux level is represented by for the month, Eq. (3) is rewritten as

Therefore, we can calculate the precise activity of reaction of interest by applying presented in Eq. (5).

Therefore, we can calculate the precise activity of reaction of interest by applying presented in Eq. (5).

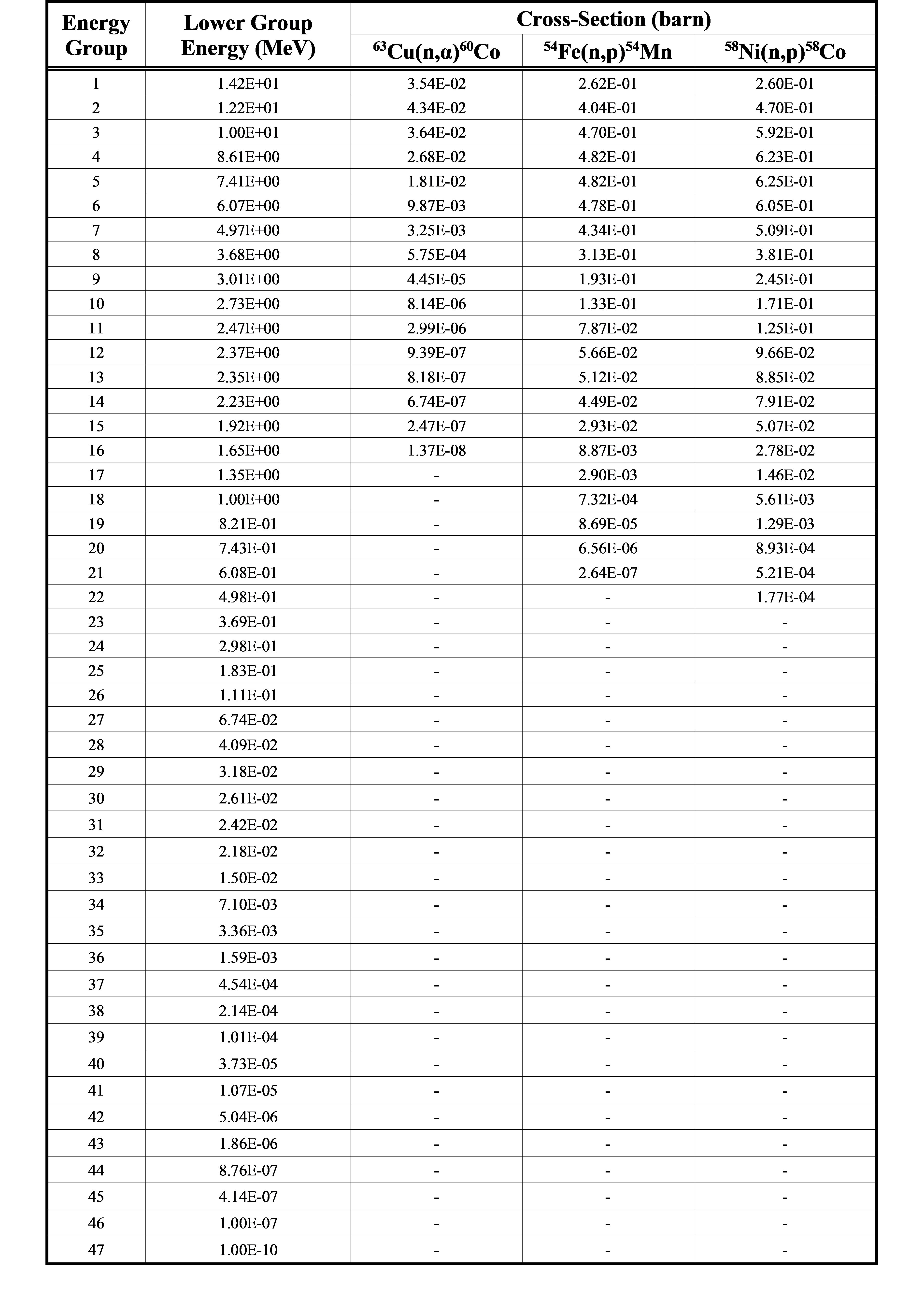

The characteristics of targets or products such as the reaction of interest, target atomic information, and product half-life are also required as input. The main characteristics of the three reactions of interest are shown in (Table 1). The group-wise microscopic cross-sections used in this study are presented in (Table 2).

Based on above, we can calculate the activity considering the plant-specific operation history.

Table 1. Radiological characteristics for the reactions of interest

* Energies between which 90% of activity is produced (235U fission spectrum). Ref. [14]

Table 2. 47 energy group and group-wise microscopic cross-sections for the reactions of interest

Neutron transport calculation

To calculate in Eq. (5), which is group-wise neutron spectrum corresponding to the full power level, the RAPTOR-M3G code was used. RAPTOR-M3G is a three dimensional parallel discrete ordinates radiation transport code developed by Westinghouse, verified by the US NRC (Nuclear Regulatory Committee) in Reference [15]. The methodology employed by RAPTOR-M3G is essentially the same as the methodology employed by the TORT code [16]. RAPTOR-M3G was designed from its inception as a parallel-processing code and adheres to modern best practices of software development.

The BUGLE‑96 cross-section library was used for the neutron transport calculations. The BUGLE-96 library provides a 67 group coupled neutron-gamma ray cross section data set produced specifically for light water reactor application. In this study, anisotropic scattering was treated with a P3 Legendre expansion and angular discretization was modeled with an S10 order of angular quadrature.

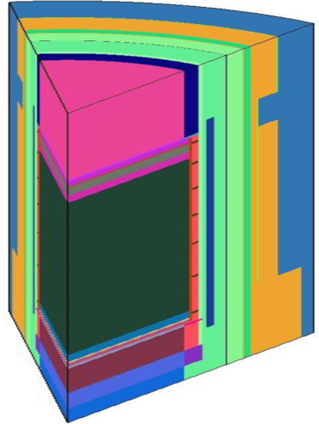

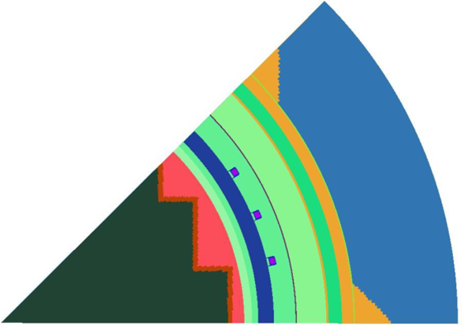

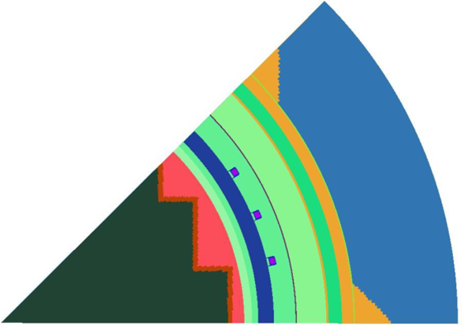

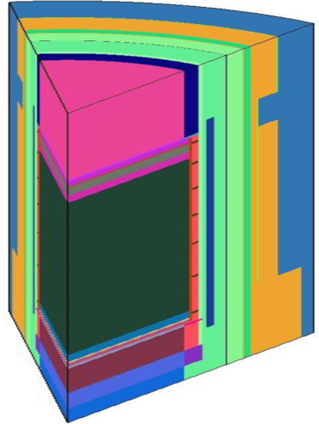

(Figure 2) shows the three dimensional neutron transport calculation model used in this study. (Figure 3) shows the plan view of reactor geometry at the core mid-plane. A single octant depicts the arrangement of thermal shield and surveillance capsule attachments. In addition to the core, reactor internals, pressure vessel and primary biological shield, the models developed for these octant geometries also include explicit representations of the surveillance capsules, the pressure vessel cladding, the pressure vessel reflective insulation, and the reactor cavity liner plate.

From a neutronic standpoint, the inclusion of the surveillance capsules and associated support structure in the analytical model is significant. Because the presence of the capsules and structure has a marked impact on the magnitude of the neutron flux and on the relative neutron and gamma ray spectra at dosimetry locations within the capsules, a meaningful evaluation of the internal capsule radiation environment can be made only when these perturbation effects are properly accounted for in the analysis.

In developing the R-θ-Z analytical models of the reactor geometry shown in (Figure 2), nominal design dimensions were employed for the different structural components. The stainless-steel former plates located between the core baffle and core barrel regions were also explicitly included in the model. The water temperatures and coolant density in the reactor core and downcomer regions of the reactor were considered to be representative of full power operating conditions (1723.5 MWth).The reactor core was considered as a homogeneous mixture of fuel, cladding, water and miscellaneous core structures such as fuel assembly grids, and guide tubes.

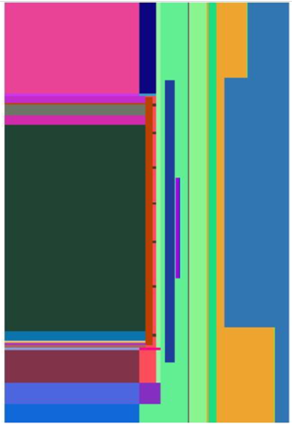

A section view of the axial geometry is shown in (Figure 4). The model extends radially from the centerline of the reactor core to a location inside the primary biological shield. The model includes the axial geometry from four feet below to six feet above the active fuel region.

The SORCERY [17] computer code was used to prepare a fixed distributed source for the RAPTOR-M3G transport calculations. This code prepares a fixed distributed source in X-Y-Z or R-θ-Z discrete ordinates transport theory code space mesh. Given initial U-235 enrichments and assembly burnup data, SORCERY properly accounts for the fission of U-235, U-238, Pu-239, Pu-240, Pu-241, and Pu-242. The radial core burnup distributions, assembly specific initial enrichments, and relative axial power distributions were obtained from the corresponding cycle-specific Nuclear Design Reports.

Neutron dosimeter measurements in surveillance capsules

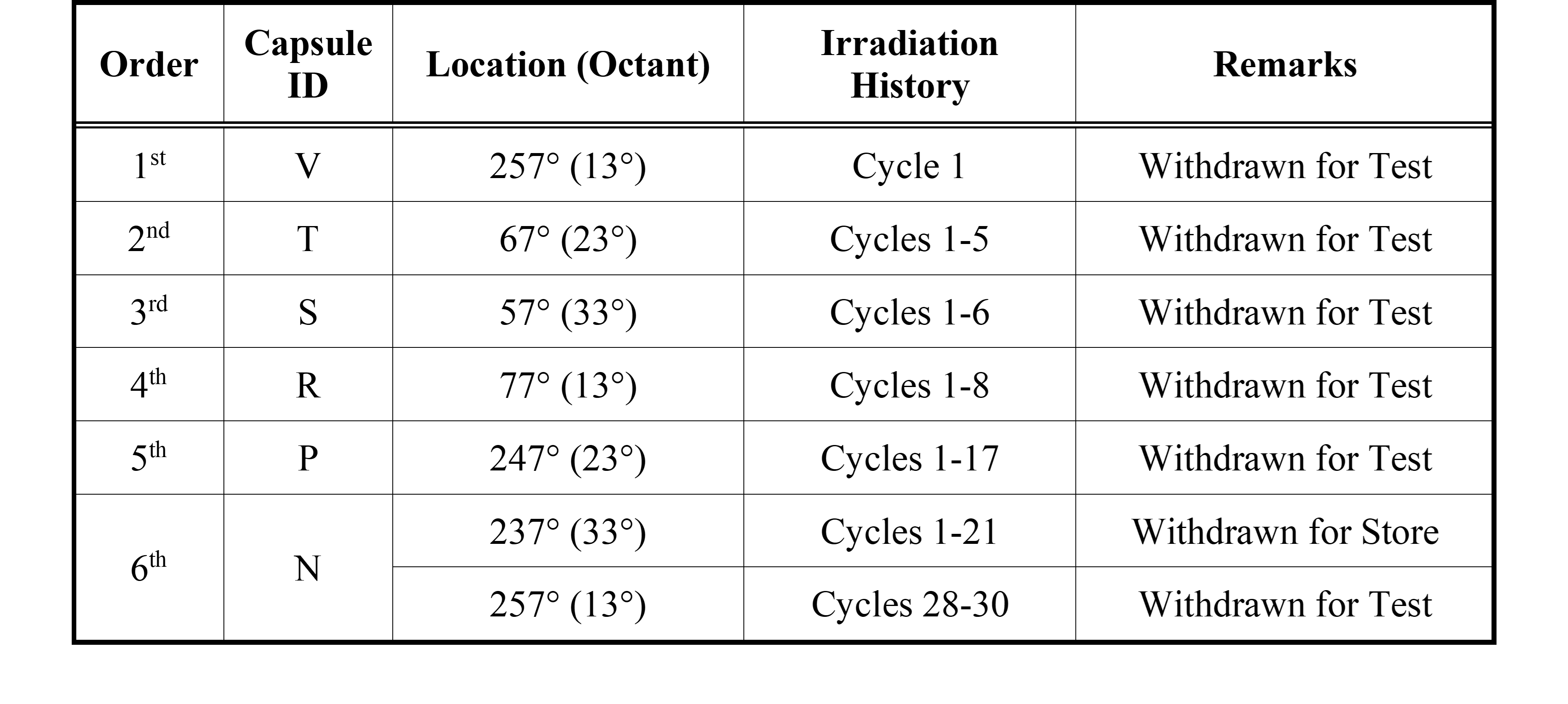

During the service life of the retired nuclear power plant, a reactor vessel surveillance program involving six surveillance capsules located between the reactor core and reactor pressure vessel was implemented to monitor the integrity of the vessel according to Final Safety Analysis Report (FSAR) [18]. The irradiation history of six surveillance capsules is shown in (Table 3).

Table 3. Locations and irradiation history of six surveillance capsules

The neutron dosimetry sensors were contained in the capsules; these sensors can provide measurement results at the surveillance capsule locations. The surveillance capsule was designed such that neutron dosimeter wires were positioned at five locations in the capsule, as in the original design. The dosimeter wires were supplied by Westinghouse and included iron, nickel, copper, and aluminum cobalt (0.15 % cobalt) shielded with cadmium tubing. The dosimeter wires were inserted into holes drilled in the spacers and were sealed in the spacers with press-fitting plugs in the holes. The five dosimeter monitor spacers containing the dosimeter wires were numbered sequentially from #1 through #5; the contents of each spacer are shown in (Figure 5). The neutron dosimetry sensors were made of pure material. Thus, there were no effects of sensor impurity when the activity was measured. Three reactions of interest (copper, iron, nickel) were selected to verify the calculation results.

To measure the activity, a high purity germanium (HPGe) gamma-ray spectroscope (detector model GC2520) with a pulse height analyzer (DSA-1000) and data processor (GENIE-2000 version 3.4) was used because of the high resolution of the semi-conductor detector. All measurements were performed at -190 °C because a germanium (Ge) semi-conductor is activated at the temperature of liquid nitrogen. To prepare the sample for measurement, the sample was immersed in a nitric acid solution for several seconds to remove the oxide film, and was then rinsed with acetone; the weight and activity of the sample were accurately measured.

The activity results measured by neutron dosimetry sensors in six surveillance capsules are provided in Reference [19]. These measured activities are used to verify the method in this study.

Results

Based on calculation considering operation history and neutron flux level, the activities were produced through RAPTOR-M3G transport code for in Eq. (5) and monthly relative reactor thermal power for in (Figure 1).

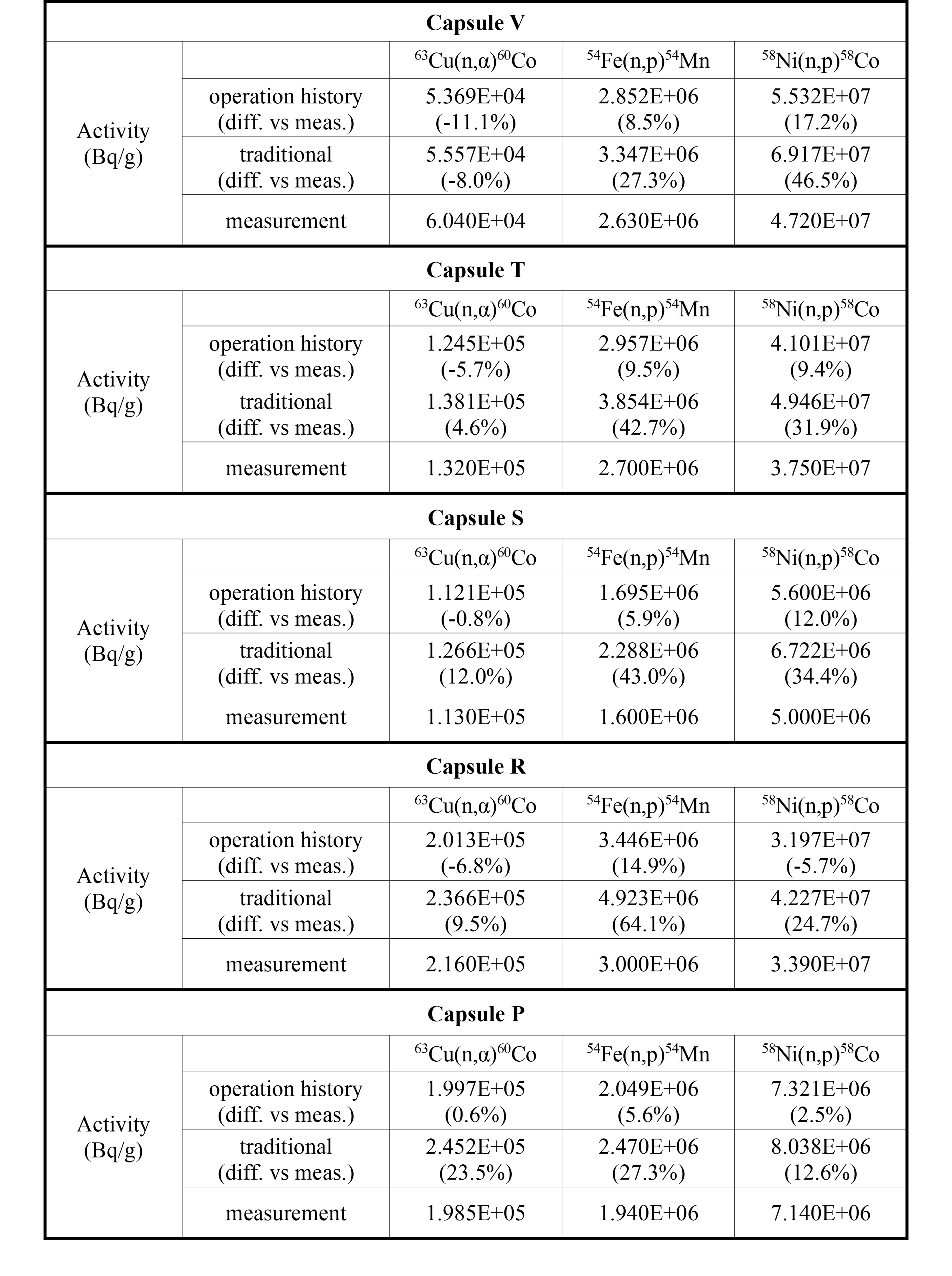

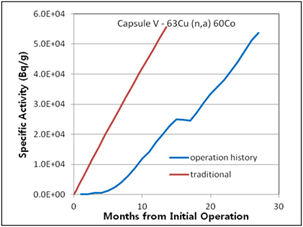

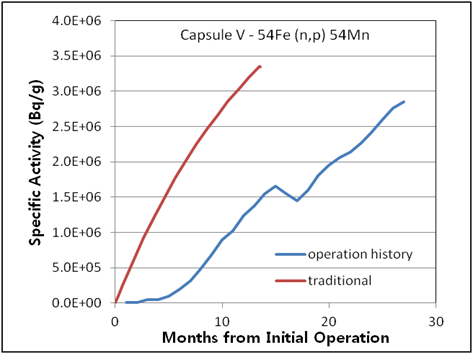

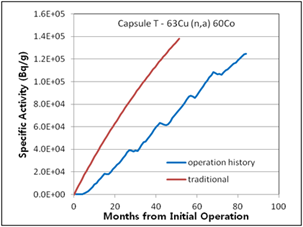

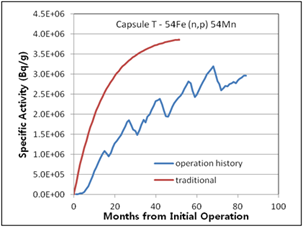

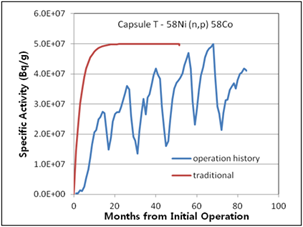

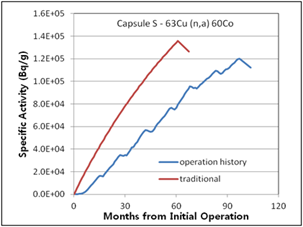

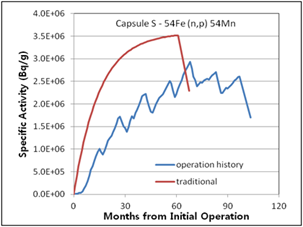

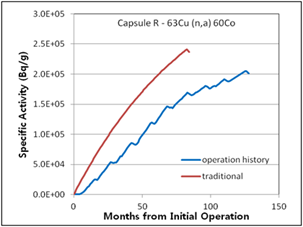

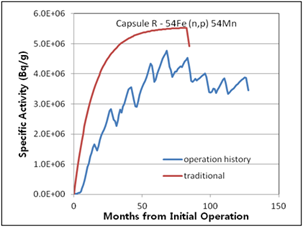

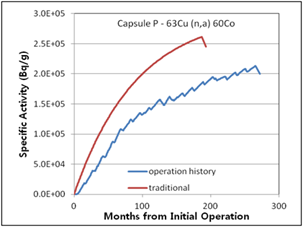

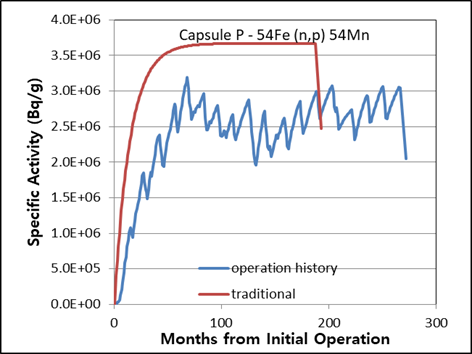

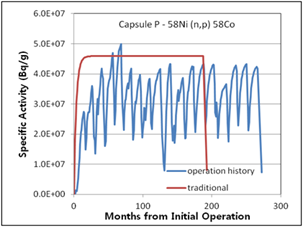

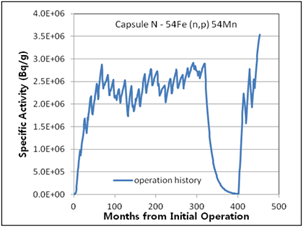

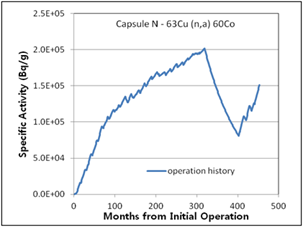

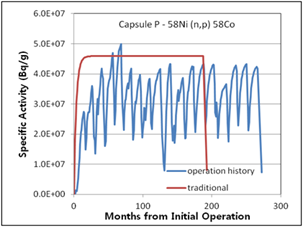

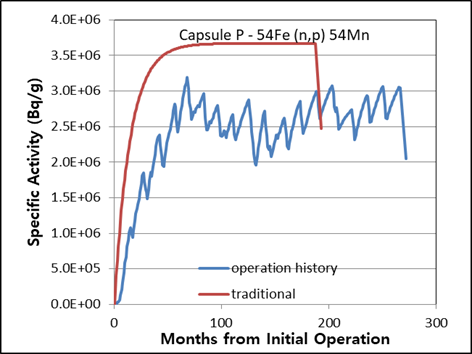

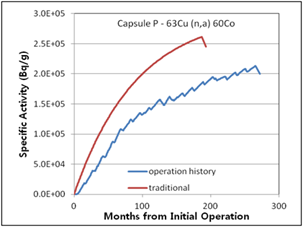

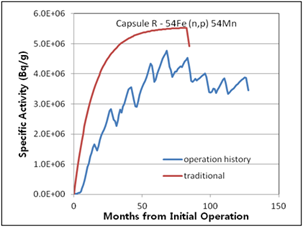

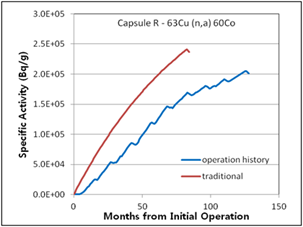

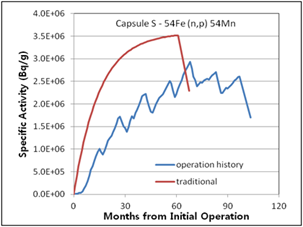

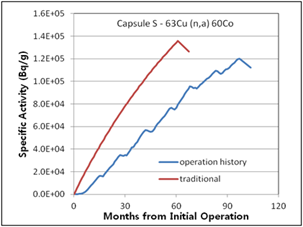

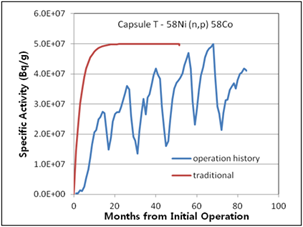

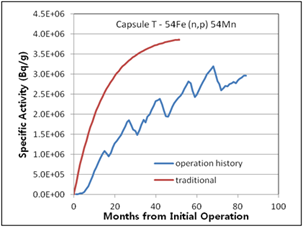

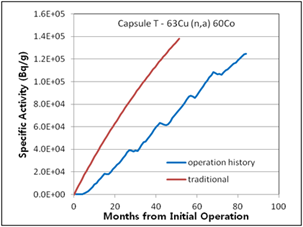

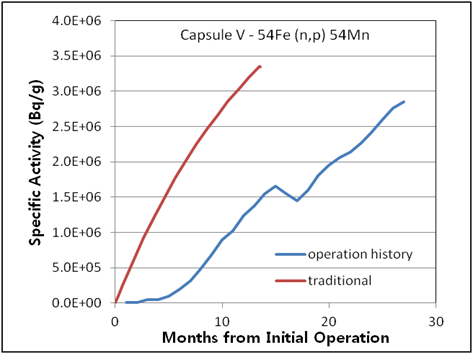

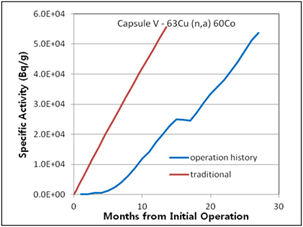

The difference in the traditional activity calculation and the activity calculation introduced in this study considering operation history was determined, as shown in (Figure 6 – 10). The relative error between the two methods ranged from 3% (Capsule V – 63Cu(n,a)60Co) to 30% (Capsule R – 54Fe(n,p)54Mn). The traditional activity calculation results were higher in all cases. In the (Figure 7, 8, and 9), the decrease curves reflect the decay until measurement after irradiation.

(Table 4) shows a comprehensive comparison between calculated activities and measured activities. There is good agreement between the calculated activity results considering operation history and measured activity results. The relative error between them is less than 17 %. The relative error between traditional method and the measured activity results reaches 64 %.

Table 4. Specific activities comparison for product nuclides between measurement and calculation for dosimeters in surveillance capsules

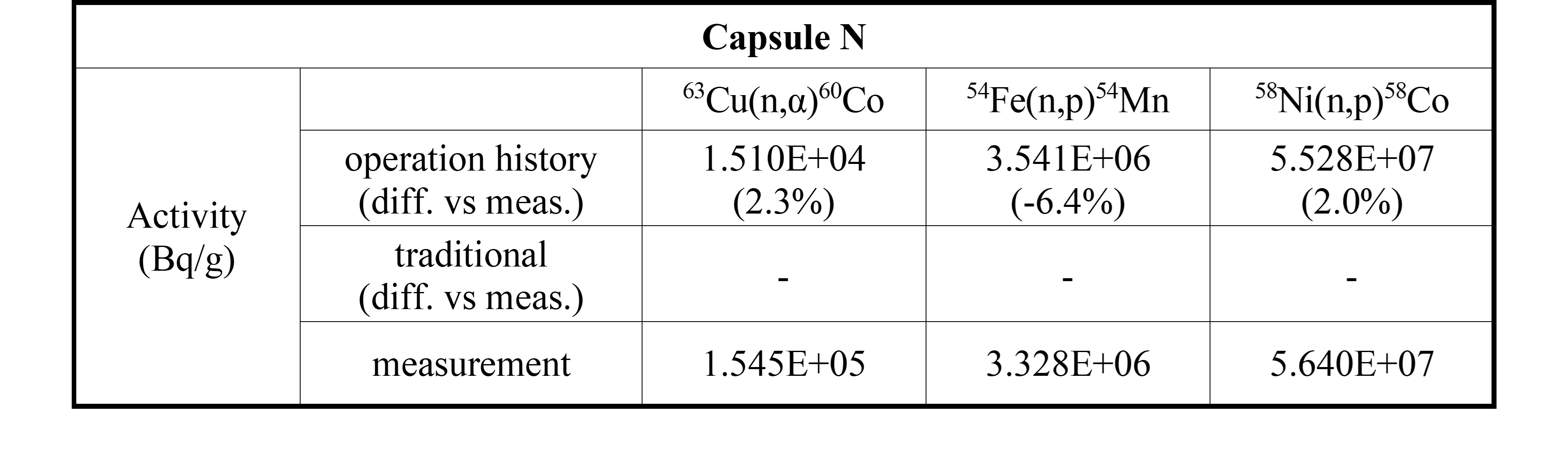

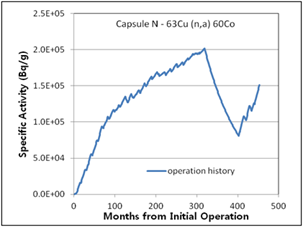

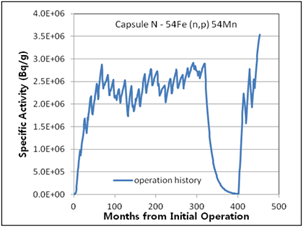

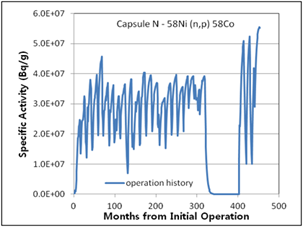

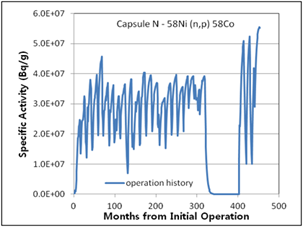

The 6th surveillance capsule, N, which has a complicated irradiation history, was excluded from this comparison. Only the activity calculation results obtained using the proposed method are shown in (Figure 11) because it is unreasonable to assume a representative production rate or flux in case of a complicated irradiation history. However, it is observed in (Table 5) that the calculated activity results considering detailed plant-specific history and the measured activity results for capsule N show good agreement.

Table 5. Specific activities comparison for product nuclides between measurement and calculation for dosimeters in surveillance capsule N

Discussion

With the long and complicated operation history of a retired nuclear power plant, consideration of the operation history in calculations is important in generating an accurate radioactivity distribution because the production rates are variable. In addition, various radionuclides must be identified before disposal and daughter nuclides with a short half-life are more sensitive to operation history. In this study, for radioactivity calculation, the detailed operation history is considered by using the thermal power ratio per month. The calculated activity results considering the detailed operation history show good agreements with measured activity results compared with traditional calculated activity results.

In the 63Cu(n,a)60Co reaction of capsules V and T in (Table 4), the traditional calculated activity results seem to fit better with measured activity results because the effect of measurement error may be larger than the effect of considering the operation history. Except for these two cases, the method considering the operation history has less error than the traditional method.

The number of target nuclides represented by in Eq. (2) is also an important parameter in the radioactivity calculation to predict and classify the amount of radioactive waste. The exact value of this parameter is unknown at this time for the retired nuclear power plant. However, in the future, this parameter would be possible to obtain by mass spectrometer through a sample; together with the operation history the radioactivity calculation would provide a reliable radioactivity distribution for decommissioning.

Conclusion

This paper proposed an activity calculation method considering a detailed plant-specific operation history; the relative power level for every month during the plant lifetime was used. To verify the method, the calculated activity results were compared with measured activity results from neutron dosimetry sensors in five surveillance capsules representing the actual irradiation environment. There is good agreement between the calculated activity and measured activity. This method can eliminate excessive conservation in calculation to prevent overestimation of worker exposure, and help establish an appropriate and reasonable dismantling and disposal strategy.

Reference

[1] INTERNATIONAL ATOMIC ENERGY AGENCY, “Decommissioning of Nuclear Facilities, IAEA-TECDOC-179,” IAEA, Vienna (1975)

[2] INTERNATIONAL ATOMIC ENERGY AGENCY, “Status of the Decommissioning of Nuclear Facilities around the World, IAEA-TECDOC-179,” IAEA, Vienna (2004)

[3] INTERNATIONAL ATOMIC ENERGY AGENCY, “Radiological Characterization of Shut Down Nuclear Reactors for Decommissioning Purposes,” Technical Reports Series No. 389, IAEA, Vienna (1998)

[4] Bouhaddane, A., and Gabriel Farkas, “Calculation of induced activity in the V-230 reactor,” (2013)

[5] Tanaka, Ken-ichi, and Jun Ueno, “ Development of a reliable estimation procedure of radioactivity inventory in an BWR plant due to neutron irradiation for decommissioning,” EPJ Web of Conferences, Vol. 153, EDP Sciences, 2017.

[6] Schlomer, Luc, Peter-W. Philippen, and Bernard Lukas, “Activation calculation for the dismantling and decommissioning of a light water reactor using MCNPTM with ADVANTG and ORIGEN-S.” EPJ Web of Conferences, Vol. 153, EDP Sciences, 2017.

[7] Volmert, Ben, et al., “Validation of MCNP NPP Activation Simulations for Decommissioning Studies by Analysis of NPP Neutron Activation Foil Measurement Campaigns,” EPJ Web of Conferences, Vol. 106, EDP Sciences, 2016.

[8] John R. Lamarsh, Introduction to Nuclear Engineering, 3rd ed. Pearson, 2001, Chapter 2.

[9] Westinghouse, LTR-REA-11-65, Rev. 0 “RAPTOR-M3G Version 2.0 User Manual”, November 3, 2011.

[10] RSIC Data Library Collection DLC-185, “BUGLE-96, Coupled 47 Neutron, 20 Gamma-Ray Group Cross Section Library Derived from ENDF/B-VI for LWR Shielding and Pressure Vessel Dosimetry Applications,” March 1996.

[11] ASTM E 523, “Standard Test Method for Measuring Fast-Neutron Reaction Rates by Radiactivation of Copper,”

[12] ASTM E 263, “Standard Test Method for Measuring Fast-Neutron Reaction Rates by Radiactivation of Iron,”

[13] ASTM E 264, “Standard Test Method for Measuring Fast-Neutron Reaction Rates by Radiactivation of Nickel,”

[14] ASTM E 844, “Standard Guide for Sensor Set Design and Irradiation for Reactor Surveillance, E706(IIC),”

[15] Westinghouse, WCAP-18124-NP-A, Revision 0, “Fluence Determination with RAPTOR-M3G and FERRET,” July 2018.

[16] RSICC Computer Code Collection CCC-650, “DOORS 3.1, One-, Two, and Three-Dimensional Discrete Ordinates Neutron/Photon Transport Code System,” August 1996.

[17] Westinghouse Electric Company LLC, “SORCERY User Manual,” December 2001.

[18] Korea Hydro and Nuclear Power Co., LTD, „Kori Unit 1 Final Safety Analysis Report“

[19] Korea Reactor Integrity Surveillance Technology, „Final Report for the 6thSurveillanceTestoftheReactorPressureVesselMaterialofKoriNuclearPowerPlantUnit1,“ March 2016.

Figure 1. Monthly normalized reactor thermal power level for the plant

Figure 2. R-θ-Z geometry for neutron transport calculations

Figure 3. Mid-plane octant geometry for neutron transport calculations

Figure 4. Axial geometry for neutron transport calculations

Figure 5. Surveillance capsule diagram showing the location of specimens and dosimeters

Figure 6. Specific activities considering operation history compared with traditional method for 1st surveillance capsule V

Figure 7. Specific activities considering operation history compared with traditional method for 2nd surveillance capsule T

Figure 8. Specific activities considering operation history compared with traditional method for 3rd surveillance capsule S

Figure 9. Specific activities considering operation history compared with traditional method for 4th surveillance capsule R

Figure 10. Specific activities considering operation history compared with traditional method for 5th surveillance capsule P

Figure 11. Specific activities considering operation history for 6th surveillance capsule N

0 Comments