Prof. Pravin Singare

–

International Trends & Developments in Nuclear

Department of Chemistry

N.M. Institute of Science, Bhavan’s College, Mumbai, India

Article

–

–

–

Studies on performance and degradation stability of chemically degraded nuclear graded ion exchange materials by application of radio analytical technique

- Introduction

Ion exchange materials plays a crucial role in various industrial processes like electrodialysis used for purification and separations of high level of anionic impurities present in water [1-8]. In nuclear industries particularly for CANDU type reactors, ion exchange materials play vital role in maintaining the high purity level of heavy water which is commonly used as a moderator/coolant. By removal of both radioactive and non-radioactive impurities from water, the resins ensure the low level of important water quality parameters namely pH and salt content responsible for specific electrical conductivity. The prolonged use of ion exchange materials will finally leads to the fall in quality of water and reduction in throughput. From the very beginning of using organic ion exchangers it was well known that washing out of water soluble degraded organic compounds from the resin materials will contaminate the treated water thereby affecting the water quality parameters to the great extent [9]. This is associated with the fact that the degradation of strongly basic anion exchange materials and sulfonic acid cation exchange materials releases quanternary ammonium bases and sulfonic acids respectively as a major degradation product. Such resin degradation products entering the coolant water get deposited on the blades of turbine there by inducing corrosion [9, 10]. There have been prolonged debates on the reasons behind accumulation of foreign matter on the resin and their oxidative degradation leading to in service deterioration in performance of resins. The resin materials will degrade under service conditions mainly due to combination of thermal and chemical degradation. The chemical degradation of resins has a great impact on their performance and degradation chemistry is well known. The mechanism of degradation is the same irrespective of the relative strength of oxidising agents such as free chlorine, nitric acid and dissolved oxygen [11]. These oxidising agents during degradation will first attack the weakest bond in the resin were the functional group attaches to the backbone. The rupture of functional group from the S-DVB matrix will increase the resin internal water retention capacity thereby weakening the resin beads; reducing the kinetic performance thereby lowering the operational capacity and increased leakage. Increase in resin water retention capacity will increase the compressibility of resin leading to channelling in the resin column, poor distribution of regenerant and short runs. In order to ensure the average resin life, it is usually recommend having low level of oxidants in the influent water entering the ion exchange column. Based on the earlier research it was reported that the presence of peroxide coupled with the metals exchanged on the resin surface will accelerate the resin degradation [12].The results of this research was supported from reactor data and laboratory experiments, along with published data on the Fugen reactor (Japan) [13] which is configurationally similar to CANDU reactor. Consequences of in service resin degradation include fouling of the resin due to loss in exchange capacity which is expected to take place after long service times and premature saturation with ions due to impurity removal which takes place irrespective of damage to resin materials. Both loss in resin exchange capacity and premature saturation affect the resin useful service life. The degradation of resin materials has adverse economical and environmental implications. From the designing and operational point of view it is essential to have firsthand knowledge regarding deterioration in performance of resin materials over repeated cycles of elution and water processing. The information regarding resin deterioration will help to estimate their useful service life, their consumption rate and also amount of spent resin material for final disposal [14]. From many years the importance of having the first hand information regarding performance deterioration of the resin materials is well known; however, the problem of monitoring resin degradation and developing suitable monitoring procedure remains unexplored [9, 15, 16].

In past the research work was performed to investigate the structural changes in the spent low level radioactive resin during oxidation and application of theromgravimetric analysis to study oxidation kinetics of resins [17]. Study was also performed on non-isothermal degradation of acrylic ion-exchange resins in air and nitrogen atmosphere up to 600°C to characterize the resins decomposition steps and the degradation products [18]. Experiments were also performed to investigate the mechanism and rate of polymer degradation at high temperatures [19]. The research work was also performed to understand changes in bulk mechanical properties, surface chemistry and surface morphology of the polymeric materials exposed to UV radiations for different exposure period [20, 21]. Research work was also carried out to investigate the role of photo-sensitizers in speeding up the UV radiation degradation efficiency and the mechanism of photo-oxidative and photolysis degradation processes in polymeric materials [22, 23]. A detailed review was also published on the role of stabilisers in photo degradation of polystyrene polymers and their degradation mechanism [24]. However, very few research work is conducted to understand the performance of chemically degraded resin particularly under in service temperature conditions [25]. Therefore in the present investigation, attempts were made to study the degradation stability and performance of chemically degraded nuclear grade resin materials on the basis of thermodynamics and kinetics data of ion-isotopic exchange reactions for which non-destructive radio-analytical technique was successfully applied. It is expected that the results of present study will help to understand the performance of resin materials exposed to stringent oxidising conditions at operating temperature.

- Materials and Methods

2.1. Ion exchange resin

Purolite NRW505 was the polystyrenic macroporous resin having total exchange capacity of 0.9 eq/L (here after referred as R1), while Purolite NRW400 was the gel polystyrene resin having total exchange capacity of 1.0 eq/L (hereafter referred as R2). Both the resins are nuclear grade Type I strong base anion exchange resin in OH– form having quaternary ammonium functional group with divinylbenzene crosslinking having particle size in the range of 425-1200 µm, operating below the maximum temperature of 60oC. Purolite NRW400 resins as supplied by the manufacturer was having moisture content of 48%, and specific gravity of 1.07, while Purolite NRW505 was having moisture content of 58% and specific gravity of 1.09. Both the resins were supplied by Purolite International India Private Limited, Pune, India.

2.2. Radio tracer isotope

The radioactive tracer isotope used in the present study was 82Br supplied by Board of Radiation and Isotope Technology (BRIT), Mumbai, India. In chemical form, the isotope consists of ammonium bromide aqueous solution in dilute ammonium hydroxide having t1/2 of 36 d, 5mCi radioactivity and 0.55 MeV γ- energy [26].

2.3. Treatment of the ion exchange resin

The resin particles of uniform particle size (30-40 mesh size) were used for the entire experimental work. The soxhlet extraction technique using distilled deionised water was used to remove the soluble impurities of the resin. The non-polymerized organic impurities of the resins were removed by using distilled methanol. The conversion of resin from hydroxide form into bromide form was performed by passing 10% potassium bromide solution through column packed with the resin. After complete conversion of resins in bromide form they were repeatedly washed with distilled deionized water for making them free of halides. The treated resins in the bromide form were air dried over P2O5 and used for further study (hereafter referred as fresh resin).

2.4. Chemical degradation of anion exchange resins

The dried and conditioned resins in bromide form weighing 10g were degraded by equilibrating them separately for 24 h with 20% and 30% H2O2 solution as well as with 0.005M and 0.010M HClO4 under uniform mechanical stirring at a constant temperature of 30.0oC. After 24h, the resins were washed alternately with distilled methanol/distilled deionised water, further air dried over P2O5 and preserved for further study (hereafter referred as chemically degraded resin).

2.5. Study on amount of bromide ions exchanged and reaction kinetics

During the experiment, 0.200M bromide ion solution (200 mL) was labeled with radioactive 82Br isotope solution in the same way as explained previously [27-30]. The γ -ray spectrometer coupled with NaI (Tl) scintillation detector was used to measure the initial radioactivity of the solution (Ai) in counts per minute (cpm). In a closed bottle, 1.000 g of the fresh resins in bromide form was equilibrated with the above solution of known initial radioactivity at a constant temperature of 30.0oC. The temperature was maintained constant by using an in-surf water bath. The bromide ion-isotopic exchange reaction taking place here can be represented as follows:

R-Br + Br*–(aq.) R-Br* + Br – (aq.) (1)

In the above reaction, R represents ion exchange resin in bromide form; Br*– represents radioactive tracer isotope.

The radioactivity in cpm of 1.0 mL reaction medium was measured for 3 h at a regular interval of every 2 minutes. The solution was transferred back to the same bottle after measuring the radioactivity. The final radioactivity of the reaction medium (Af) was recorded after 3h. The background radioactivity was subtracted from radioactivity of solution recorded at different time intervals to give the corrected radioactivity. From the knowledge of Ai, Af and the amount of exchangeable bromide ions in 200 mL of reaction medium, the amount of bromide ions exchanged on the resin (mmol) and percentage of bromide ions exchanged were calculated. Similar study was also repeated for chemically degraded resins. The study was also extended further by equilibrating the fresh/chemically degraded resins with 0.300M and 0.500M labeled bromide ion solution at a constant temperature of 30.0oC. Similar experimental sets were also repeated at a higher temperatures extending up to 45.0oC.

- Results and discussion

In the present investigation rapid decrease in radioactivity of the labeled solution was observed that during the initial stage due to the rapid ion-isotopic exchange reaction. In final stage of the reaction, due to slow ion-isotopic exchange the radioactivity of the solution was observed to decreases slowly which latter on remains nearly constant. Our previous research work has demonstrated that these ion-isotopic exchange reactions are of first order in which the rapid and slow ion-isotopic exchange reactions were occurring simultaneously [27-30]. As a result a graph of log radioactivity (cpm) as a function of time (min) was a composite curve in which initial radioactivity decrease sharply and latter on very slowly giving nearly straight line curve. On resolution of this composite curve, the radioactivity exchanged due to rapid and slow ion-isotopic exchange reactions as well as the specific reaction rate (k) in min-1 of rapid process were calculated [27-30]. From the knowledge of initial and final radioactivity of solution as well as the amount of ions in 200mL labeled solution, the amount of bromide ions exchanged on the resin surface (mmol) were calculated.

3.1 Stability and performance evaluation of chemically degraded resins based on kinetics of ion-isotopic exchange reaction

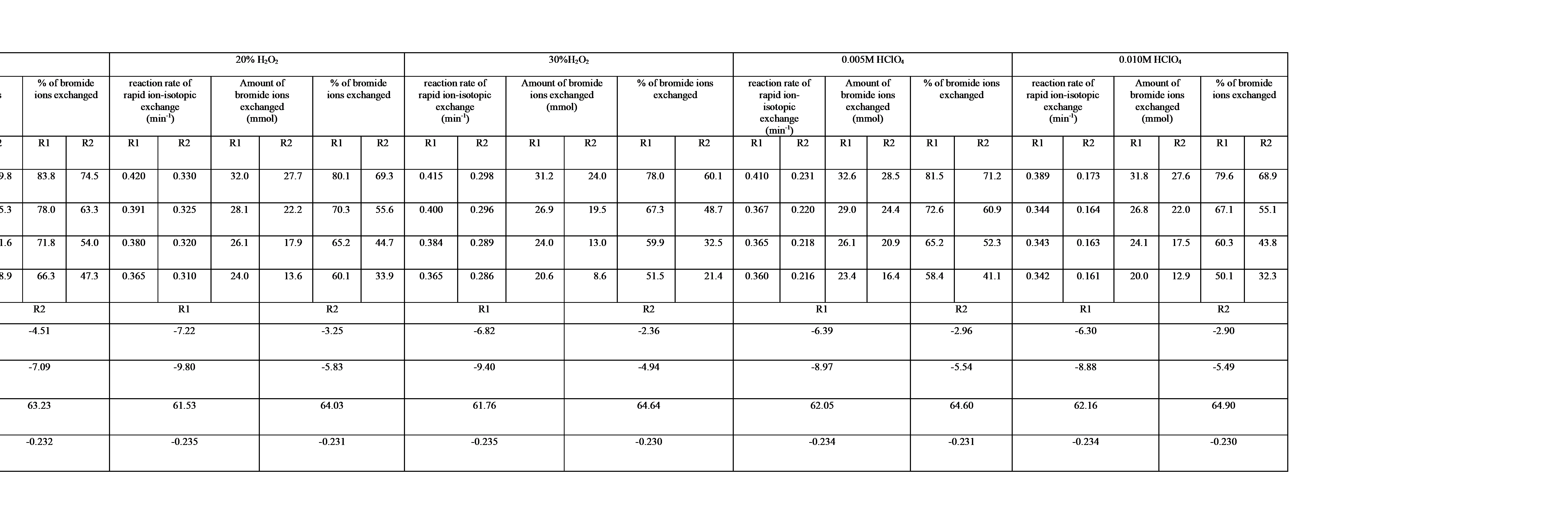

It was observed that, under identical experimental conditions, with rise in temperature from 30.0°C to 45.0°C, the k values (min-1) for bromide ion-isotopic exchange reactions were observed to decrease for fresh as well as chemically degraded resins which were degraded in H2O2/ HClO4 medium of increasing strength (Table 1). Thus for 0.200M radioactive labeled bromide ion concentration, when the temperature was raised from 30.0 oC to 45.0 oC, the respective k values for R1 and R2 resins decreases from 0.428 to 0.370 min-1 and 0.356 to 0.327min-1 for fresh resin; from 0.420 to 0.365 min-1 and 0.330 to 0.310 min-1 for resins degraded in 20% H2O2 medium; from 0.415 to 0.365 min-1 and 0.298 to 0.286 min-1 for resins degraded in 30% H2O2 medium; from 0.410 to 0.360 min-1 and 0.231 to 0.216 min-1 for resins degraded in 0.005M HClO4 medium; from 0.389 to 0.342 min-1 and 0.173 to 0.161 min-1 for resins degraded in 0.010M HClO4 medium (Table 1). From the results, it appears that under identical experimental conditions, bromide ion-isotopic exchange reaction rate decreases sharply with increase in strength of H2O2/ HClO4 degradation medium. Thus under identical experimental conditions of 0.200M radioactive labeled bromide ion concentration at a constant temperature of 30.0 oC, the k values in min-1 for reactions performed by using fresh R1 (0.428 min-1) and R2 (0.356 min-1) resin decreases to 0.420 and 0.330 min-1 respectively for the reactions performed by using resins degraded in 20% H2O2 medium, which further decreases to 0.415 and 0.298 min-1 respectively for the reactions performed by using resins degraded in 30% H2O2 medium (Table 1). Similarly trend was observed for the reactions performed by using resins degraded in HClO4 degradation medium in which the k values obtained for the fresh R1 and R2 resins decreases to 0.410 and 0.231 min-1 respectively for the resins degraded in 0.005 M HClO4 medium, which further decreases to 0.389 and 0.173 min-1 respectively for the resins degraded in 0.010 M HClO4 medium (Table 1).

It was observed that, for the reactions performed at the constant temperature of 30.0 oC, with rise in concentration of exchangeable bromide ions in the solution from 0.200M to 0.500M, the k values (min-1) for bromide ion-isotopic exchange reactions were observed to increase for fresh as well as for chemically degraded resins (Table 2). Thus for constant temperature of 30.0 oC, with rise in concentration of exchangeable bromide ions in the solution, the respective k values for R1 and R2 resins increases from 0.428 to 0.471 min-1 and 0.356 to 0.381 min-1 for the reactions performed by using fresh resin; from 0.420 to 0.451 min-1 and 0.330 to 0.353 min-1 for the reactions performed by using resins degraded in 20% H2O2 medium; from 0.415 to 0.437 min-1 and 0.298 to 0.309 min-1 for the reactions performed by using resins degraded in 30% H2O2 medium; from 0.410 to 0.433 min-1 and 0.231 to 0.247 min-1 for the reactions performed by using resins degraded in 0.005M HClO4 medium; from 0.389 to 0.406 min-1 and 0.173 to 0.182 min-1 for the reactions performed by using resins degraded in 0.010M HClO4 medium (Table 2). Thus from the results it appears that under identical experimental conditions the k values (min-1) for R1 resin were higher than R2 resin indicating their better performance and stability of R1 resin even under the stringent degradation condition (Tables 1 and 2).

3.2 Stability and performance evaluation of chemically degraded resins based on the percentage of bromide ions exchanged

For the ion-isotopic exchange reactions performed by using fresh as well as chemically degraded R1 and R2 resins, the percentage of bromide ions exchanged was observed to decrease with rise in temperature of the reaction medium (Table 1). Thus for the reactions performed by equilibrating fresh resins with 0.002M exchangeable bromide ion solution, with rise in temperature of the reaction medium from 30.0oC to 45.0oC the percentage of bromide ions exchanged decreases from 83.8% to 66.3% for fresh R1 resin and from 74.5% to 47.3% for fresh R2 resin. This corresponds to the decrease by 17.5% and 27.2% respectively for the two resins. Similarly with rise in temperature of reaction medium, the percentage of bromide ions exchanged decreases by 20.0 and 35.4% respectively for resins degraded in 20% H2O2 medium; by 26.5 and 38.7% respectively using resins degraded in 30% H2O2 medium; by 23.1 and 30.1% respectively using resins degraded in 0.005M HClO4 medium; by 29.5 and 36.6% respectively using resins degraded in 0.010M HClO4 medium. The percentage decrease in bromide ions exchanged as a function of temperature for the ion-isotopic exchange reactions performed by using fresh resins and resins degraded in H2O2 and HClO4 medium of different strength is graphically represented in Figure 1. From the figure 3 it is clear that during the ion-isotopic exchange reactions performed by using the resins degraded in the degradation medium of increasing strength, the decrease in percentage of bromide ions exchanged was more for R2 resins as compared to R1 resins.

For the ion-isotopic exchange reactions performed by using fresh as well as chemically degraded R1 and R2 resins, the percentage of bromide ions exchanged was observed to increase with rise in concentration of reaction medium from 0.200M to 0.500M (Table 2). Thus for the reactions performed at 30.0oC, as the concentration of the reaction medium was gradually increase, the percentage of bromide ions exchanged increases from 83.8% to 93.9% using fresh R1 resin and from 74.5% to 83.3% using fresh R2 resin which corresponds to increase by 10.1% and 8.8% respectively. Similarly with rise in concentration of reaction medium the percentage of bromide ions exchanged by using R1 and R2 resins increase by 8.5 and 6.5% respectively for resins degraded in 20% H2O2 medium; by 7.7 and 5.4% respectively by using resins degraded in 30% H2O2 medium; by 5.1 and 3.0% respectively by using resins degraded in 0.005M HClO4 medium; by 3.9 and 1.9% respectively by using resins degraded in 0.010M HClO4 medium. The percentage increase in bromide ions exchanged as a function of concentration of reaction medium for the ion-isotopic exchange reactions performed by using fresh resins and resins degraded in H2O2 and HClO4 medium of different strength is graphically represented in Figure 2. From the figure 4 it is clear that during the ion-isotopic exchange reactions performed by using the resins degraded in the degradation medium of increasing strength, the increase in percentage of bromide ions exchanged was more for R1 resins as compared to R2 resins.

Thus on the basis of percentage of bromide ions exchanged with rise in temperature and concentration of reaction medium it can be concluded that R1 resin show excellent performance than R2 resin even under stringent degradation conditions.

3.3 Stability and performance evaluation of chemically degraded resins based on thermodynamics of ion-isotopic exchange reaction

From the results obtained for the bromide ion-isotopic exchange reactions performed by using fresh and chemically degraded resins, various thermodynamic parameters namely energy of activation, enthalpy, entropy and free energy of activation were calculated. Based on the Arrhenius equation

k = A x e–E(ac)/RT (2)

the graph of log (10) k against 1/T was plotted (Figure 3) from the slope of which the energy of activation (Eac) for the bromide ion-isotopic exchange reactions was calculated [31].

By using Eyring-Polanyi equation,

log10k/T = -ΔH*/2.303RT + log10kB/h + ΔS* /2.303R (3)

the straight line graph of log10k/T against 1/T was plotted (Figure 4). The enthalpy of activation ΔH* was calculated from the slope of the graph, while the entropy of activation ΔS* was calculated from the intercept of the graph [31, 32] using the equation

Intercept = 2.303 x log10 (kB/h) + ΔS*/R (4)

In the above equations, k is the reaction rate constant; T is the absolute temperature (in Kelvin); R is the gas constant having value 8.314J.K−1.mol−1; kB is the Boltzmann constant having value 1.3806 ×10−23J⋅K−1; h is the Planck’s constant having the value 6.6261×10−34J⋅s.

From the value of ΔH* and ΔS*, free energy of activation ΔG* for bromide ion-isotopic exchange reactions was calculated.

It was observed that for ion-isotopic exchange reaction performed by using fresh R1 resin, the values of energy of activation, enthalpy of activation, free energy of activation and entropy of activation was -7.54 kJ.mol-1 , -10.12 kJ.mole-1, 61.33 kJ.mol-1 and -0.236 kJ.K-1mol-1 which was less than the respective values of -4.51 kJ.K-1mol-1,-7.09 kJ.K-1mol-1, 63.23 kJ.mole-1 and -0.232 kJ.K-1mol-1 obtained for fresh resin R2. Similar trend was observed for the reactions performed by using both resins degraded in H2O2/ HClO4 medium of increasing strength (Table 1). The values of above thermodynamic parameters gradually increases for the reactions performed by using fresh resins and resins degraded in degradation medium of increasing strength (Table 1), indicating decrease in thermodynamically feasibility of the reactions. Also the increase in values of above thermodynamic parameters for the reactions performed by using fresh and degraded R1 resin was less than that obtained for the reactions performed by using fresh and degraded R2 resin (Figure 5). This indicate that the bromide ion-isotopic exchange reactions are thermodynamically more feasible using R1 resin in comparison to R2 resin thereby suggesting that the superior performance of R1 resin even under stringent degradation conditions.

Amount of degraded ion exchange resin in bromide form = 1.000 g; Concentration of labeled bromide ion reaction medium = 0.200M; Volume of labeled bromide ion reaction medium = 200 mL; Amount of exchangeable bromide ions in 200 mL labeled reaction medium = 40.0 mmol

Table 1. Effect of temperature of reaction medium on ion-isotopic exchange reaction kinetics using fresh and chemically degraded resins.

3.4 Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis of the experimental data was made by using one way ANOVA method. Criterion of significance selected was P<0.02 and P<0.01. The IBM SPSS statistics version 20 was used for all statistical calculations.

From the results of the present study, it seems that there exists a good negative correlation between temperature of the medium and reaction rate (r = -0.736; P< 0.01) for the reactions performed by using R1 resins as compared to R2 resin showing extremely poor correlation with value of r = -0.098 (Table 3). There also exists a strong negative correlation between temperature of reaction medium and amount of bromide ions exchanged for both R1 and R2 resins having r value of -0.891 and -0.880 respectively with P< 0.01. Similar strong negative correlation was observed between temperature of reaction medium and percentage of bromide ions exchanged for both R1 and R2 resins having r value of -0.891 and -0.879 respectively with P< 0.01. A good positive correlation exist between reaction rate and amount of bromide ions exchanged (r = 0.804; P< 0.01) as well as between reaction rate and percentage of bromide ions exchanged (r = 0.802; P< 0.01) for the reactions performed by using R1 resin as compared to R2 resin which show relatively poor relationship (Table 3).

The results also indicate a good positive relationship between the concentration and reaction rate for the reactions performed by using R1 resins, having r values of 0.513 (P< 0.02), while for R2 resins extremely poor relationship was observed (r = 0.097) (Table 4). A strong positive correlation was observed between the concentration and amount of bromide ions exchanged for the reactions performed by using R1 and R2 resins, having r values of 0.994 and 0.980 respectively with P< 0.01. There also exists a strong positive correlation between reaction rate and percentage of bromide ions exchanged for R1 resins having r value of 0.905 (P< 0.01) as compared to R2 resin which show relatively poor relationship. For the reactions performed by using R1 resins somewhat satisfactory relationships exist between reaction rate and amount of bromide ions exchanged (r = 0.590), between concentration and percentage of bromide ions exchanged (r = 0.646) as compared to R2 resin which show relatively poor relationship (Table 4).

- Conclusions

It is now well established fact that the ion exchange resins having wide technological applications, experience oxidative degradation in perchloric and peroxide medium. The chemical degradation of resin materials is one of the serious issues associated with organic resins. In the present study, the kinetics and thermodynamics of ion-isotopic exchange reactions was studied for chemically degraded nuclear grade Purolite NRW505 and Purolite NRW400 resins. The results of the present study gives an indication that ion-isotopic exchange reaction rate (min-1), percentage of ion-isotopic exchange are largely affected during the reactions performed by using resins degraded in increase in strength of degradation medium. The higher k values (min-1) for the ion-isotopic exchange reaction and higher percentage of bromide ions exchanged using Purolite NRW505 resin indicate their superior performance even under the stringent degradation conditions as compared to Purolite NRW400 resin. The degradation effect on the resins was also reflected from the decrease in values of thermodynamic parameters namely energy of activation (kJ.mol-1), enthalpy of activation (kJ.mole-1), free energy of activation (kJ.mol-1) and entropy of activation (kJ.K-1mol-1) calculated for the reactions performed by using the fresh and degraded resin. The low values of various thermodynamic parameters obtained for the bromide ion-isotopic exchange reactions performed by using fresh as well as chemically degraded Purolite NRW505 resin indicate that the reactions are thermodynamically more feasible using that resin as compared to Purolite NRW400 resin there by confirming the degradation stability and superior Purolite NRW505 resin.

Acknowledgement

The author is thankful to Professor Dr. R.S. Lokhande (Retired) for his valuable help and support by providing the required facilities so as to carry out the experimental work in Radiochemistry Laboratory, Department of Chemistry, University of Mumbai, Vidyanagari, Mumbai -400 058.

Funding

This research did not receive any financial support from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

References

- M. Oldani, E. Killer, A. Miguel, G. Schock, On the nitrate and monovalent cation selectivity of ion

exchange membranes used in drinking water purification, J. Memb. Sci. 75 (1992) 265–275,

https://doi.org/10.1016/0376-7388(92)85068-T.

- S.Samatya, N. Kabay, N. Yuksel, M. Arda, M. Yuksel, Removal of nitrate from aqueous solution by

nitrate selective ion exchange resins, React. Funct. Polym. 66 (2006) 1206–1214,

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.reactfunctpolym.2006.03.009.

- R. Haghsheno, A. Mohebbi, H. Hashemipoura, A. Sarrafi, Study of kinetic and fixed bed operation of

removal of sulfate anions from an industrial wastewater by an anion exchange resin, J. Hazard. Mater.

166 (2009) 961–966, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2008.12.009.

- B. Bolto, D. Dixon, R. Eldridge, S. King, K. Linge, Removal of natural organic matter by ion

exchange, Water Res. 36 (2002) 5057–5065, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0043-1354(02)00231-2.

- J. Balster, O. Krupenko, I.Punt, D.F. Stamatialis, M. Wessling, Preparation and characterisation of

monovalent ion selective cation exchange membranes based on sulphonated poly (ether ether ketone),

- Memb. Sci. 263 (2005) 137–145, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.memsci.2005.04.019.

- K. A. Indarawis, T.H.Boyer, Superposition of anion and cation exchange for removal of natural

water ions, Sep. Purif. Technol. 118 (2013) 112–119, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seppur.2013.06.044.

- A. Oehmen, D. Vergel, J. Fradinho, M.A.M. Reis, J. G. Crespo, S. Velizarov, Mercury removal from

water streams through the ion exchange membrane bioreactor concept, J.Hazard. Mater. 264 (2014) 65–

70, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2013.10.067.

- J.A. Wisniewski, M. K. Korbutowicz, S. Lakomska, Ion-exchange membrane processes for Br – and

BrO3– ion removal from water and for recovery of salt from waste solution, Desalination 342 (2014) 175–

182, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.desal.2013.07.007.

- T.I. Petrova, V.N. Voronov, B.M. Larin, Tekhnologiya organizatsii vodno-khimicheskogo rezhima

atomnykh elektrostantsii (Technology for Organization of Water Chemical Regime at Nuclear Power

Plants), Moscow: MEI, pp. 81–82 (2012).

- B.M. Larin, A.B. Larin, The State of the Technology of Treatment of the Aqueous Working Medium

at Russian Thermal Power Stations, Thermal Engineering, 61 (2014) 68-72,

https://doi.org/10.1134/S0040601514010078.

- T. Chuuman, K.Abe, Y. Minato, N.Orita, Degradation of ion exchange resin by vanadium-containing

water, J.Ion Exchange, 25 (2014) 252-255, https://doi.org/10.5182/jaie.25.252.

- J. Torok, F. Caron, Carbon-14 Chemistry in CANDU Moderator System, in Proc. Canadian Nuclear

Society, 21st Annual Canadian Nuclear Society Conference, June 11-14, 2000, Toronto, ON, Canadian

Nuclear Society (2000).

- T. Kitabata, N. Sakurai, Experience of water chemistry control in Fugen NWR, 2nd International

Topical Meeting on Nuclear Power Plant Thermal Hydraulics and Operations, p. 11.47 (1988).

- S.T. Arm, D.L. Blanchard, S.K. Fiskum, Chemical degradation of an ion exchange resin processing

salt solutions, Separation and Purification Technology, 43 (2005) 59–69,

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seppur.2004.10.001.

- A. Leybros, A. Roubaud, P. Guichardon, O. Boutin, Ion exchange resins destruction in a stirred

supercritical water oxidation reactor, The J. Supercrit. Fluids, 51(2010) 369–375,

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.supflu.2009.08.017.

16. B.V. Konovalov, M.D. Kravchishina, N.A. Belyaev, A.N. Novigatsky, Determination of the

concentration of mineral particles and suspended organic substance based on their spectral absorption,

Oceanology, 54 (2014) 660–667, https://doi.org/10.1134/S0001437014040067.

- Y.J. Huang, H.P. Wang, C.C. Chao, H.H.Liu, M. C. Hsiao, S. H. Liu, Oxidation Kinetics of Spent Low-

Level Radioactive Resins, Nuclear Science and Engineering, 151 (2005) 355–360,

https://doi.org/10.13182/NSE05-A2555.

- D. Chambree, C. Iditoiu, E. Segal, A. Cesaro, The study of non-isothermal degradation of acrylic ion-

exchange resins, Journal of Thermal Analysis and Calorimetry,82 (2005) 803-811,

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10973-005-0967-0.

- D. W. Haas, B. F. Hrutfiord, K. V. Sarkanen, Kinetic study on the alkaline degradation of cotton

Hydrocellulose, J. Appl. Polym.Sci., 11 (1967) 587-600, https://doi.org/10.1002/app.1967.070110408.

- B.G. Kumar, R.P. Singh, T. Nakamura, Degradation of carbon fiber-reinforced epoxy composites by

ultraviolet radiation and condensation, Journal of Composite Materials, 36 (2002) 2713-2721,

https://doi.org/10.1177/002199802761675511.

- A.W. Signor, M.R. VanLandingham, J.W. Chin, Effect of ultraviolet radiation exposure on vinyl ester

resins: characterization of chemical, physical, mechanical damage, Polymer Degradation and Stability,

79 (2003) 359-368, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0141-3910(02)00300-2.

- L.F.A. Pinto, B.E. Goi, C.C. Schmitt, M.G. Neumann, Photodegradation of polystyrene films

containing UV- visible sensitizers, Journal of Research Updates in Polymer Science, 2 (2013) 39–47,

- P. Gijsman, M. Diepens, Photolysis and photooxidation in engineering plastics. In M. C. Celina,

N.C. Billingham, J. S. Wiggins (Eds.), Polymer degradation and performance (pp.287-306).

(ACS Symposium Series; Vol. 1004). Washington: American Chemical Society, (2009),

DOI: 10.1021/bk-2009-1004.ch024

- E. Yousif, R. Haddad, Photodegradation and photostabilization of polymers, especially polystyrene:

review, SpringerPlus, 2 (2013) 398, https://doi.org/10.1186/2193-1801-2-398.

- A.N. Patange, Study on ion exchange behavior of nuclear grade resin AuchliteARA9366 chemically

degraded in hydrogen peroxide medium, Oriental Journal of Chemistry 33 (2017)1001-1010,

http://dx.doi.org/10.13005/ojc/330255.

- D.D. Sood, Proceedings of International Conference on Applications of Radioisotopes and

Radiation in Industrial Development, edited by D.D. Sood, A.V.R. Reddy, S.R.K. Iyer, S.

Gangadharan, G. Singh, BARC, Mumbai, India, p.47, (1998).

- P.U. Singare, Non-destructive radioanalytical technique in characterization of anion exchangers

Amberlite IRN78 and Indion H-IP, J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 299 (2014) 591–598,

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10967-013-2793-3.

- R. S. Lokhande, P. U. Singare, T. S. Prabhavalkar, The application of the radioactive tracer technique to

study the kinetics of bromide isotope exchange reaction with the participation of strongly basic anion

exchange resin Indion FF-IP, Russian Journal of Physical Chemistry A, 82 (2008)1589–1595,

https://doi.org/10.1134/S0036024408090331.

- P.U. Singare, Radioactive tracer application to study the thermodynamics of ion exchange reactions

using Tulsion A-23 and Indion-454, Ionics, 21(2015) 1623–1630, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11581-014-

1345-3.

- R. S. Lokhande, P. U. Singare, S. R. D. Tiwari, Application of Br-82 as a radioactive tracer isotope to

study bromide ion-isotopic exchange reaction in strongly basic anion exchange resin Duolite A-161,

Russian Journal of Physical Chemistry A, 83 (2009)1389–1394,

https://doi.org/10.1134/S003602440908024X.

- L.K. Onga, A. Kurniawana, A.C. Suwandi, C.X. Linb, X.S. Zhao, S. Ismadji, Transesterification of

leather tanning waste to biodiesel at supercritical condition: Kinetics and thermodynamics studies, The

Journal of Supercritical Fluids, 75 (2013) 11–20, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.supflu.2012.12.018.

32. V. Stavila, J. Volponi, A.M. Katzenmeyer, M.C. Dixon, M.D. Allendorf, Kinetics and mechanism of

metal– organic framework thin film growth: systematic investigation of HKUST-1 deposition on QCM

electrodes, Chem. Sci., 3 (2012) 1531-1540, https://doi.org/10.1039/C2SC20065A.

0 Comments