Minhee Kim

Junkyu Song, Kyungho Nam

International Trends & Developments in Nuclear

Central Research Institute, Korea Hydro & Nuclear Power Co., Daejeon, Korea

Article

–

–

–

–

Assessment of Loss of Shutdown Cooling System Accident during Mid-Loop Operation in LSTF Experiment using SPACE Code

I.Introduction

During a plant outage, while the fuel remains in the core, the core is cooled by Residual Heat Removal (RHR) system. The loss of RHR can lead to loss of heat removal from the core and is a safety concern. During certain stage of maintenance, such as installation of steam generator nozzle dams, the RCS coolant level is lower to centerline of hot leg and cold leg pipes. This is called mid-loop operation and the coolant level is lowest while the fuel remains in the core. Therefore, the loss of RHR during mid-loop operation represents the most limiting condition for loss of RHR incidents. The accident can be occurred by an isolation valve closure or a loss of vital ac power in the RHR suction line, or a loss of RHR pump flow due to air ingestion. If the loss of RHR flow should continue for a certain period of time, the reactor vessel coolant has possibility on core boiling and uncover.

In order to analyze the thermal hydraulic phenomena following the loss of RHR accident, the numerical and experimental studies have been performed. Nakamura et al. conducted the experiments of loss of RHR accident during mid-loop operation in the ROSA-IV/LSTF facility [1]. In the experiments, the primary pressurization behavior after the coolant boiling in the core was observed. Also, the system integral responses were investigated through analyzing the steam and noncondensable gas behavior in the RCS. The opening location and size in a pressurizer or a horizontal leg was analyzed as major experimental parameters.

In numerical approach, the major thermal hydraulic phenomena and process were evaluated using RELAP5 system code [1, 2]. The calculation results were compared with ROSA-IV/LSTF experimental data.

The present paper is focused on the assessment of SPACE 3.0 in predicting the system primary and secondary behavior following the loss-of-RHR accident during the mid-loop operation of LSTF experiment in reference to NUREG/IA-0143 report [2]. The calculated results are compared with RELAP5 results and experimental data in terms of steady-state and transient behavior.

II.Code Descriptions

The SPACE code, which is Safety and Performance Analysis Code for Nuclear Power Plants, has been developed in recent years by the Korea Hydro & Nuclear Power Co. through collaborative works with other Korean nuclear industries and research institutes, and is approved by Korea Institute of Nuclear Safety (KINS) in March 2017. The SPACE is a best-estimate two-phase three-field thermal-hydraulic analysis code in order to analyze the performance and evaluate the safety of pressurized water reactors. Each field equation is discretized based on finite volume approach on a structured mesh and an unstructured mesh together with an one-dimensional pipe meshes [7]. For time integration method, the semi-implicit scheme is used. The SPACE code is package of input and output, hydrodynamic model, heat structure model, and reactor kinetics model.

The input package performs a reading the input and restart files, a parsing the data files, an allocating the memory, and checking the unit conversion. Hydrodynamic model package is composed of constitutive models, special process models, and component models, and hydraulic solver. The hydraulic solver is based on two-fluid, three-field governing equations, which are composed of gas, continuous liquid, and droplet fields. Therefore, SPACE code have the advantage in solving a dispersed liquid field as well as vapor and continuous liquid fields in comparison with existing nuclear reactor system analysis codes, such as RELAP5 (ISL, 2001), TRACE (NRC, 2000), CATHARE (Robert et al., 2003), and MARS-KS (KAERI, 2006). Constitutive models are composed of correlations by the flow regime map to simulate the mass, momentum, and energy distributions, such as surface area and surface heat transfer, surface-wall friction, droplet separation and adhesion, and wall-fluid heat transfer. In order to analyzed the physical phenomena of the NPP, special process and system components are modeled. Major special process and component models are critical flow model, counter current flow limit model, off-take model, abrupt area change model, 2-phase level tracking model, pump model, safety injection tank model, valve model, pressurizer model, and separator model, etc.

The package of heat structure model calculates the heat addition transfer and removal. The heat structure model includes transient heat conduction of rectangular or cylindrical geometry, and has various boundary conditions of convection, radiation, user defined variables such as temperature, heat flux, and heat transfer coefficient.

In order to calculate the nuclear fission heat of a fuel rod, the point kinetics methodology is used in the heat conduction equation. Reactivity feedbacks are considered in terms of moderator temperature, boron concentration fuel moderator density, reactor scram, and power defect. Decay heat of ANS-73, -79, and -2005 models are also implemented.

The 3.0 version of the code was released through various validation and verification using the separated or integral loop test data and the plant operating data. The approved code version will be used in the safety analysis of operating PWR and the design of an advanced reactor.

III.Modeling Information

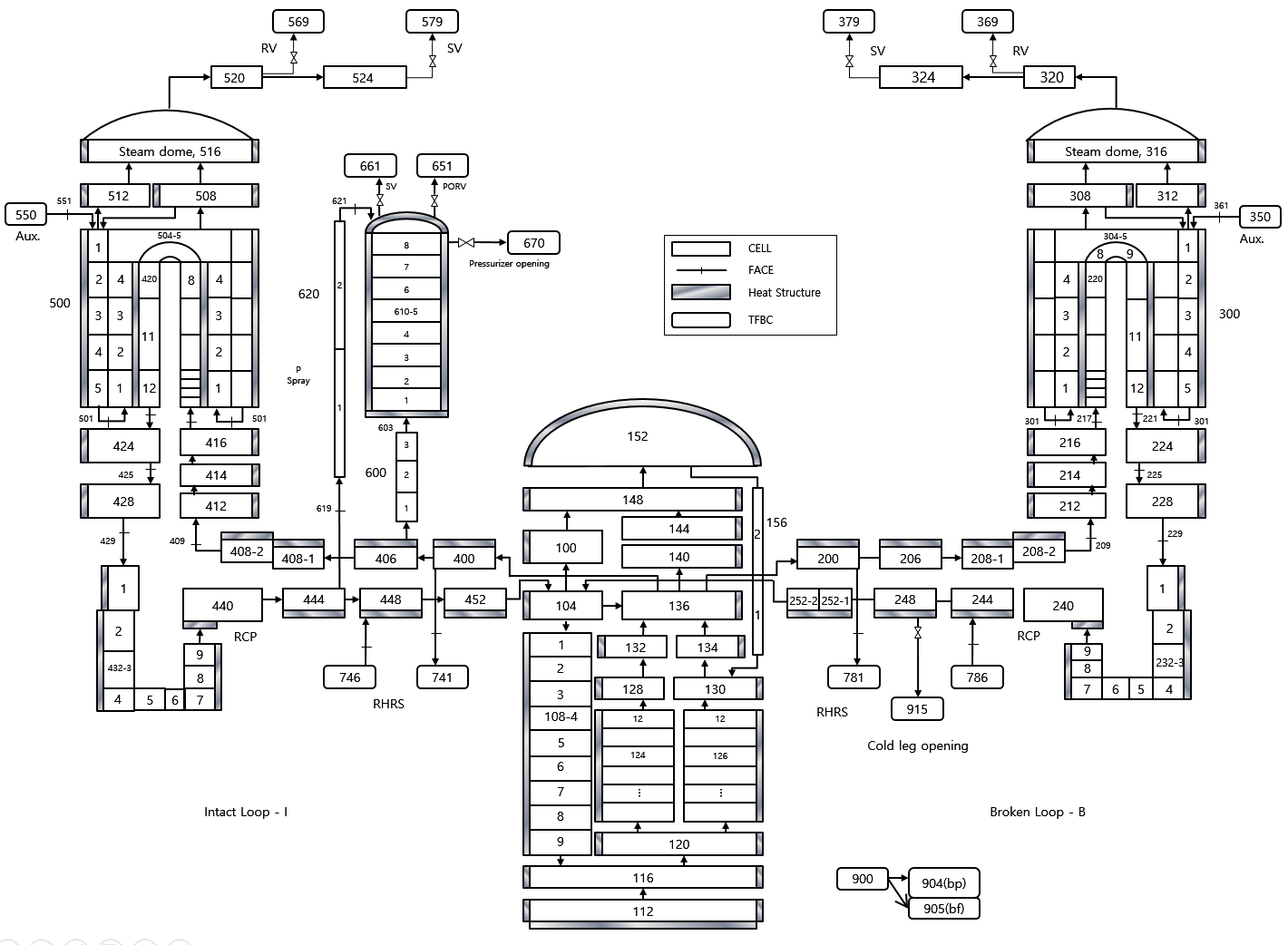

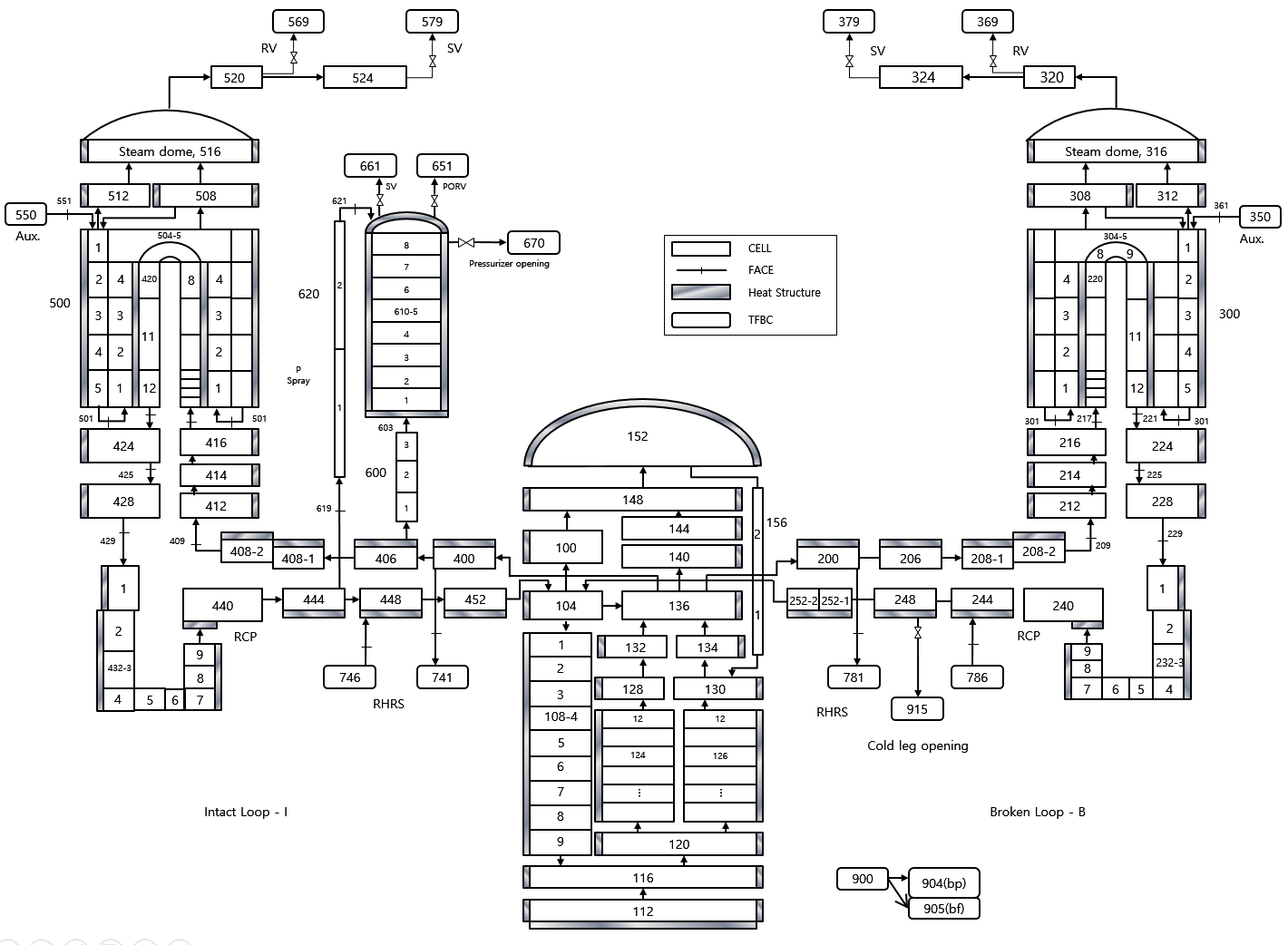

Figure 1 shows the nodalization to simulate the LSTF facility with the SPACE code. The modeling is based on 179 hydrodynamic cell and 202 heat structures. The reactor pressure vessel includes the lower plenum, upper plenum, downcomer, and core, upper head and guide thimble channel (cell 100 to 156). The core is modeled as two channel with 12 cells per each channel connected by crossflow. The two channel arrangement is adopted in order to assess the multi-dimensional effect such as the natural circulation behavior in the core. The power distribution of the two channel core is 60 % for high power channel and 40 % for low power channel.

The LSTF system are described by an intact-loop (cell 400 to 499) and a broken-loop (cell 200 to 299) in an almost symmetrical way. Each loop consists of a SG inlet and outlet, loop seal, SG U-tube, reactor coolant pump, hot leg, and cold leg. The pressurizer is connected to the hot leg of intact-loop through the surge line elements. The secondary sides of two SGs (cell 300 to 399 and 500 to 599) are composed using an identical nodalization.

In order to analyze the cold leg opening with loss of RHR accident, the openings are modeled by a trip valve. The opening sizes are equivalent to 5 % of cold leg cross area, and the opening are located at centerline of the cold legs. The steady-state results are established for conducting a null transient calculation.

IV.Results and Discussions

A. Initial conditions

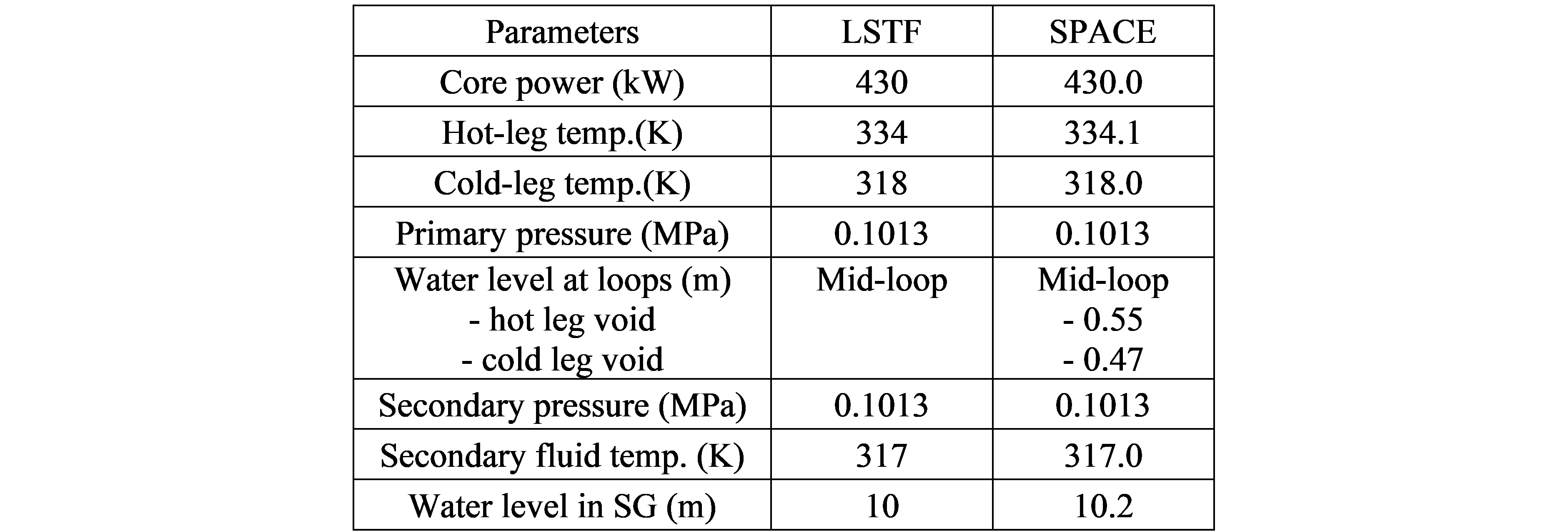

In order to confirm the modeling methodology and input condition, the steady-state calculation result is compared with experimental data. The major parameters in steady-state condition are summarized in Table 1. The core power was 430 kW with decay heat at about 20 hours after the reactor shut down. The water levels of hot and cold legs maintain at the middle of the loop. Core power and loop temperature were set to target values for calculation. Initial conditions of loop water level represent the same value with target data. The pressurizer and SGs relief valves were opened to maintain an atmospheric pressure. Overall results show that SPACE code have a reasonable agreement with target values in steady state analysis. The steady-state results are established for conducting a null transient calculation.

B. Transition behavior

The transient calculation was initiated by decreasing the RHR pump flow rate from the initial value to zero during 20 seconds with opening the cold leg valve. The pressurizer and SGs relief valves were closed with cold leg opening.

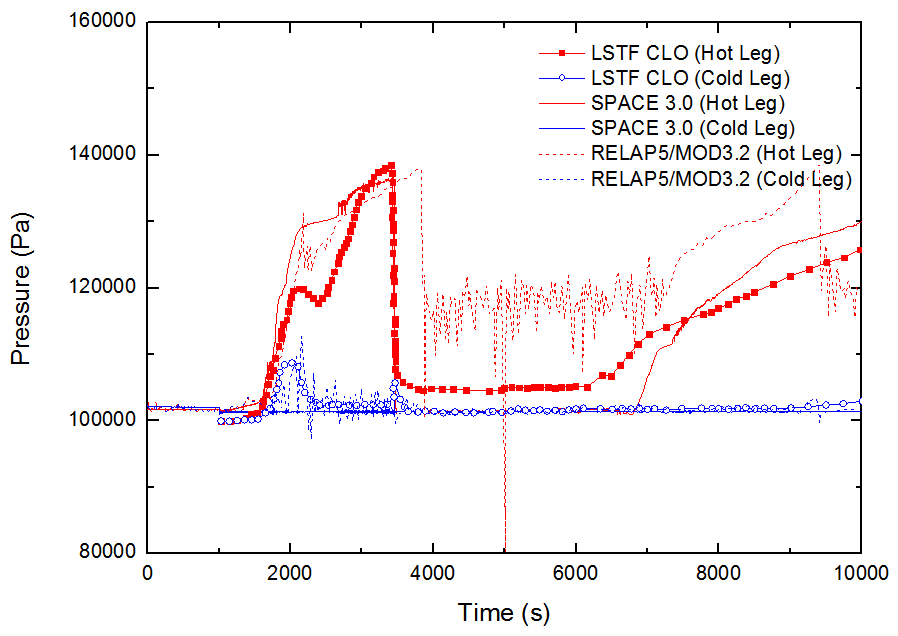

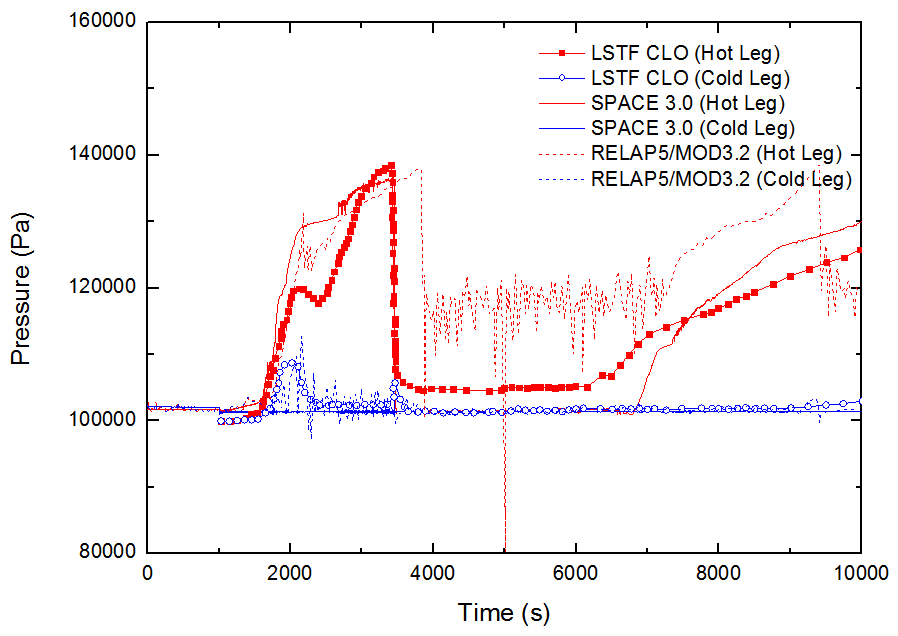

Figure 2 shows the pressure phenomena of hot and cold legs in intact loop after the loss of RHR accident. At about 1,500 seconds, the core liquid started to boil and the steam migrated toward the hot legs from the core through core upper plenum. Thus, the pressure in the hot leg started increasing rapidly at about 1,600 seconds. At about 2,100 seconds, the pressurization rate reduced immediately.

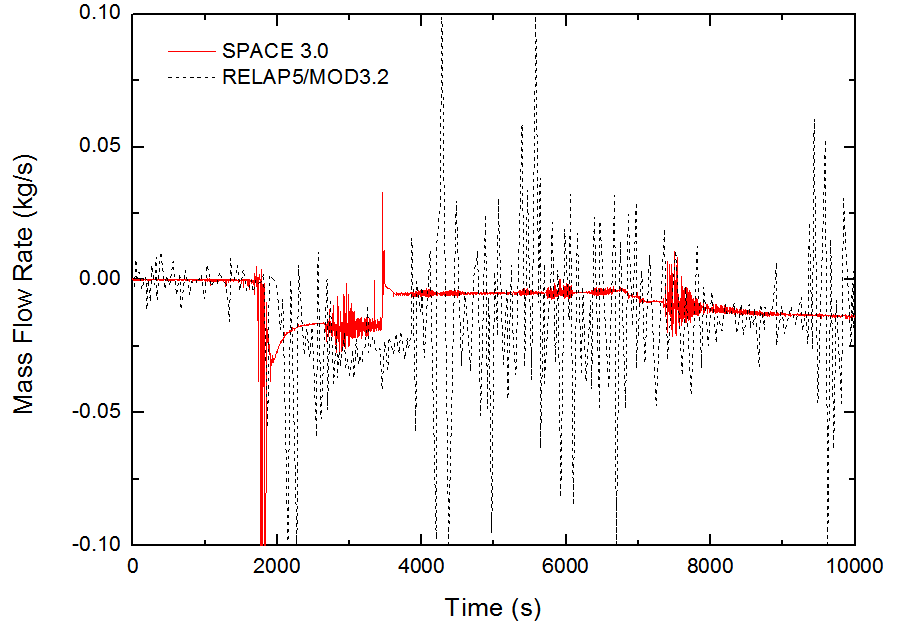

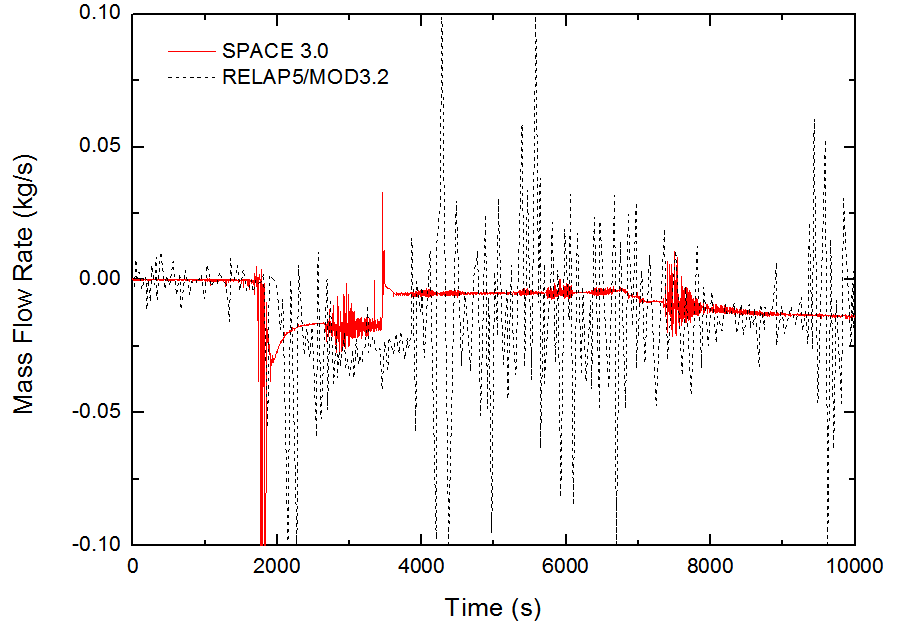

The steam flow of guide tubes express the cause and effect of pressure behavior at this time as shown in Fig. 3. The guide tubes were initially submerged under water in upper plenum. As the water level decreased below the guide tube bottom opening due to the boil off, the steam started to be discharged into upper head with large volume. The SPACE 3.0 code showed that the pressurization rate was higher than the RELAP5/MOD3.2 results. The high pressurization rate resulted in the accurate simulation of Loop Seal Clearing (LSC) comparing with experiment.

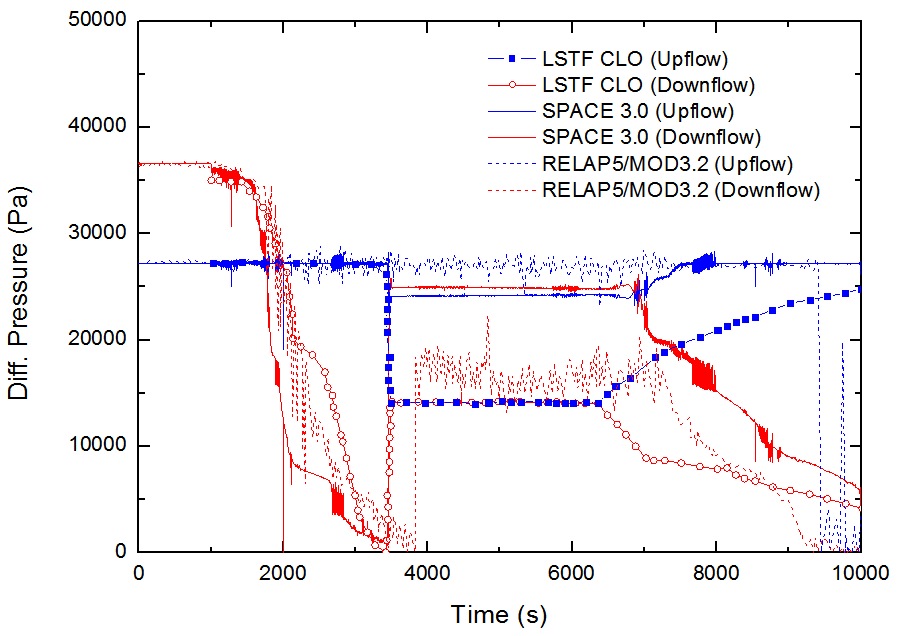

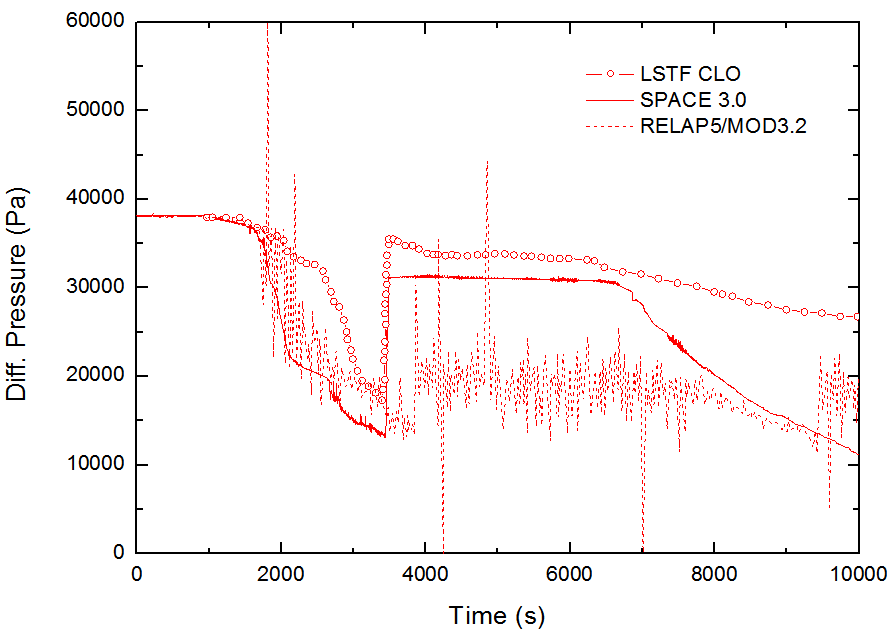

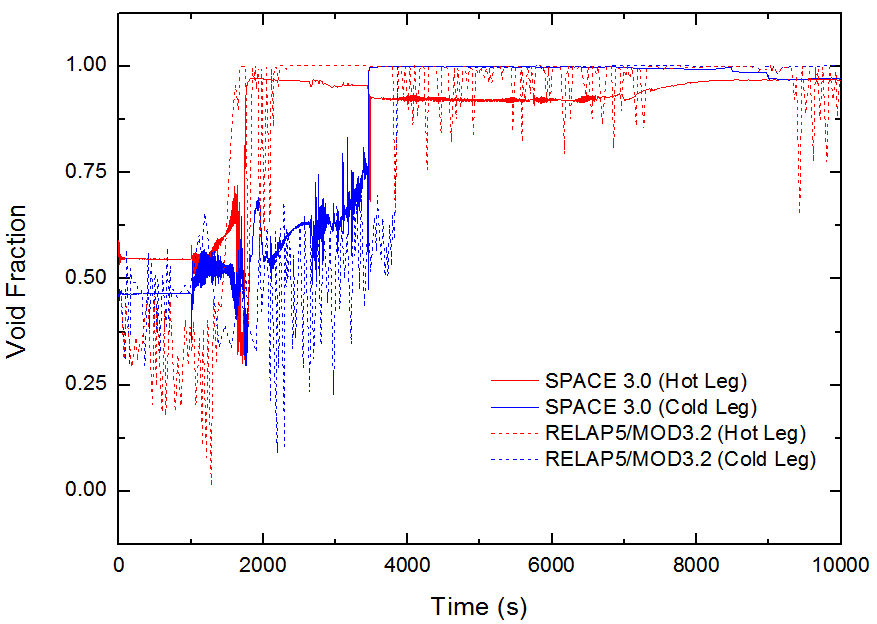

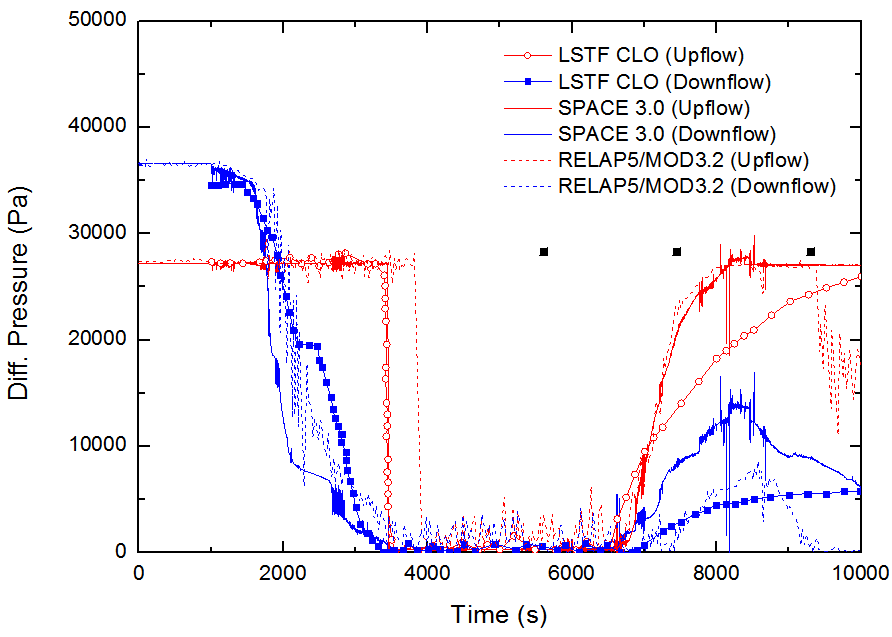

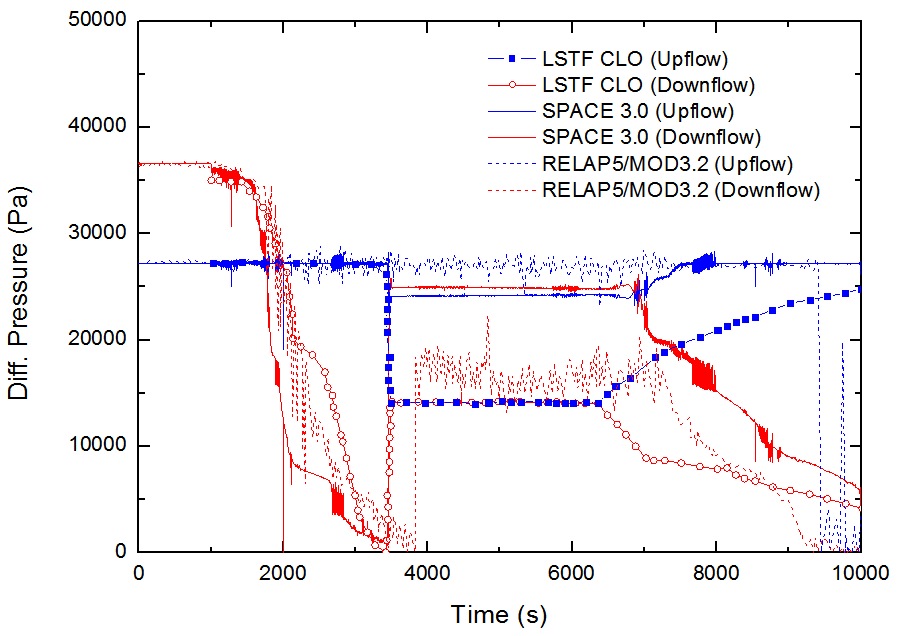

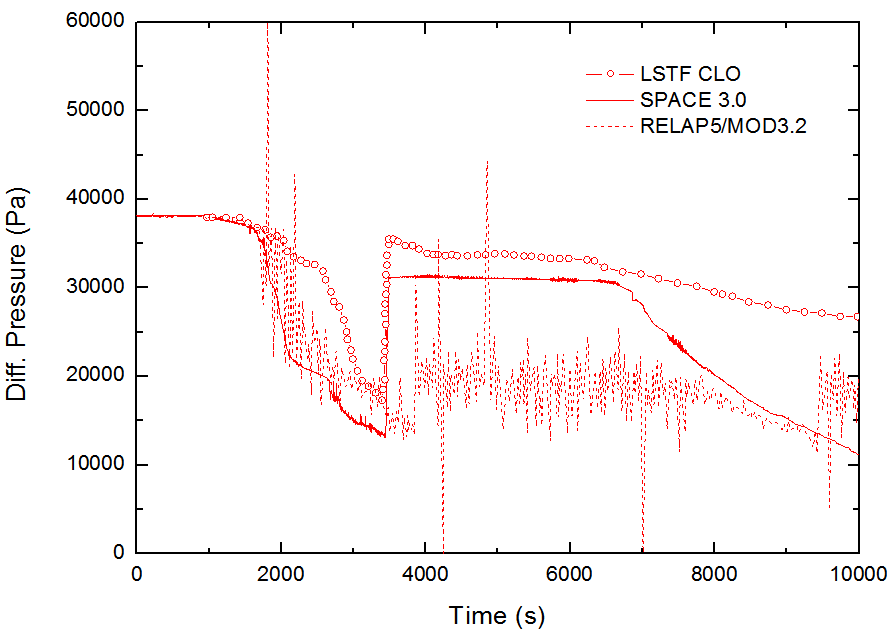

Figures 4 and 5 show the differential pressure behavior of downflow and upflow sides in the crossover legs. When the Loop-Seal Clearing(LSC) occurred, the crossover leg of broken loop was immediately emptied. The calculation well predicted the overall LSC behavior. Figure 4 also shows that the condensate liquid from the SG U-tube wall started to accumulate in upper flow direction from about 6,400 seconds. Such a liquid accumulation of the crossover leg resulted in preventing the gas flow from the hot leg to the cold leg. Because of limited steam condensation of SG U-tube wall, the pressure is re-increasing gradually in the hot leg as shown in Fig. 2.

In the intact loop, the differential pressure after the LSC was predicted a little higher than that before the LSC. The partial LSC means that the inflow from the core to the cold leg was lower than in the experiment. Because of this small amount of the inflow, the coolant inventory of the core is underestimating. Figure 6 represents that the differential pressure behavior in the core was underestimated after the LSC.

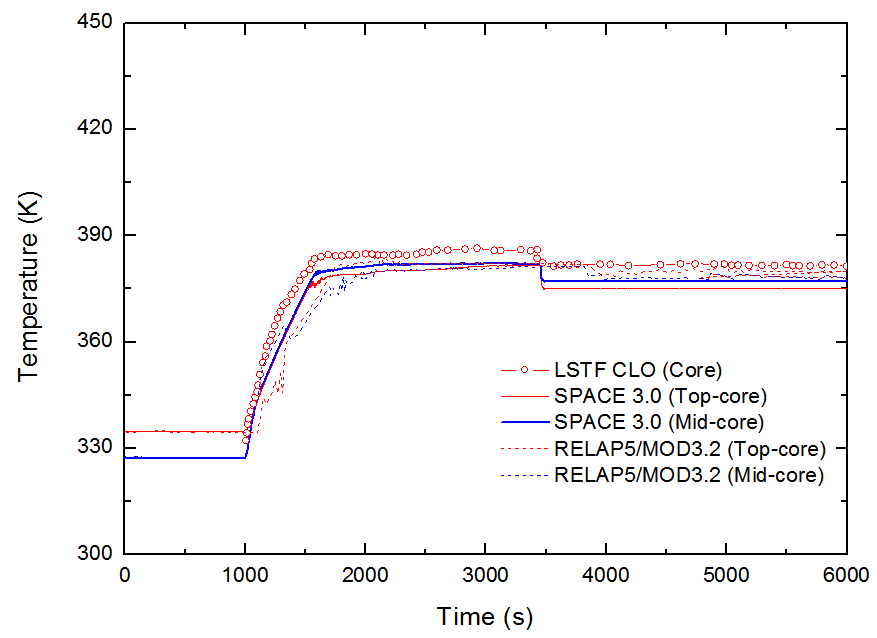

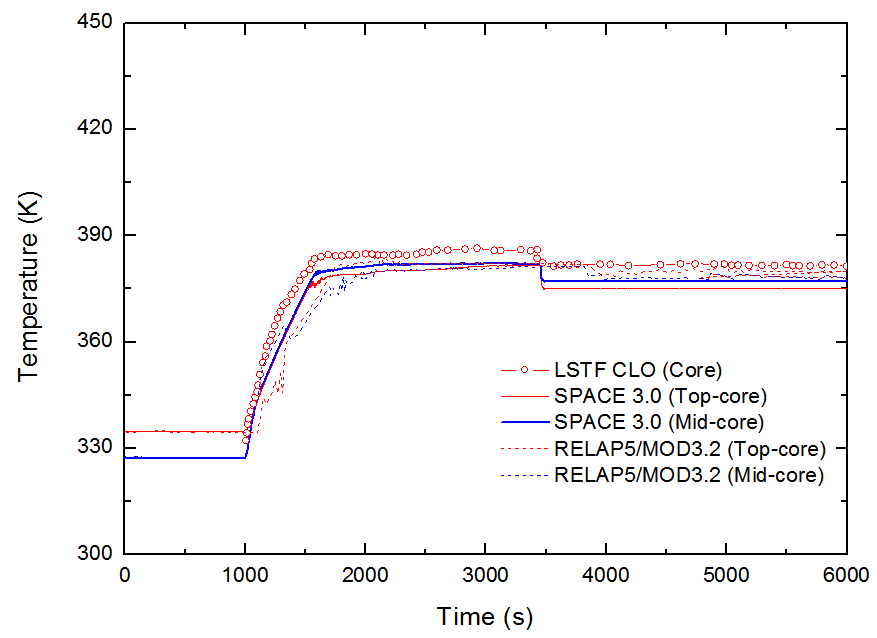

Figure 7 represents liquid temperatures behavior at the reactor core. The experimental data are fluid temperatures at midsection of the core. The core coolant became stagnated and the liquid temperature behavior immediately increased. After the liquid temperature reached saturation value, the coolant started to boil off and the temperature remained constant over time. The calculation results agreed well with the experiment data.

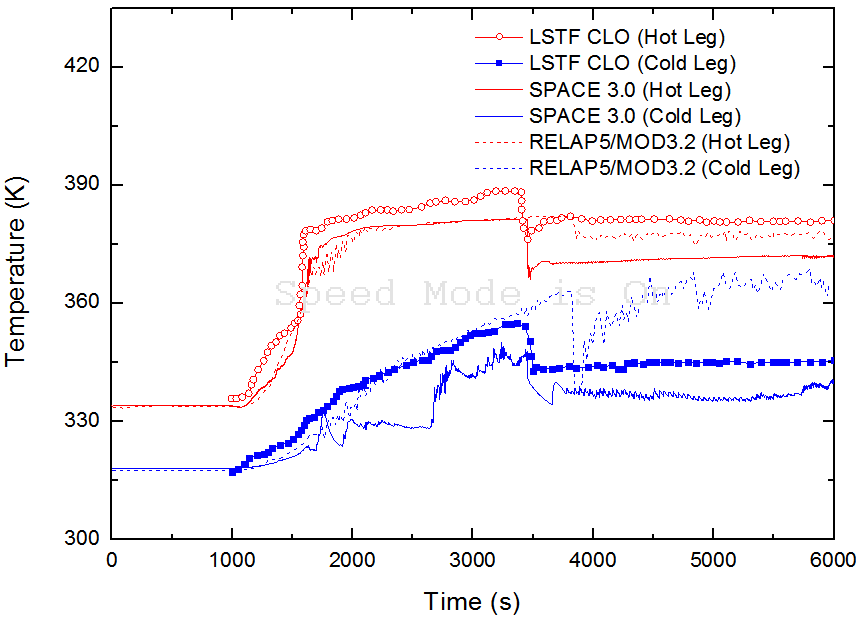

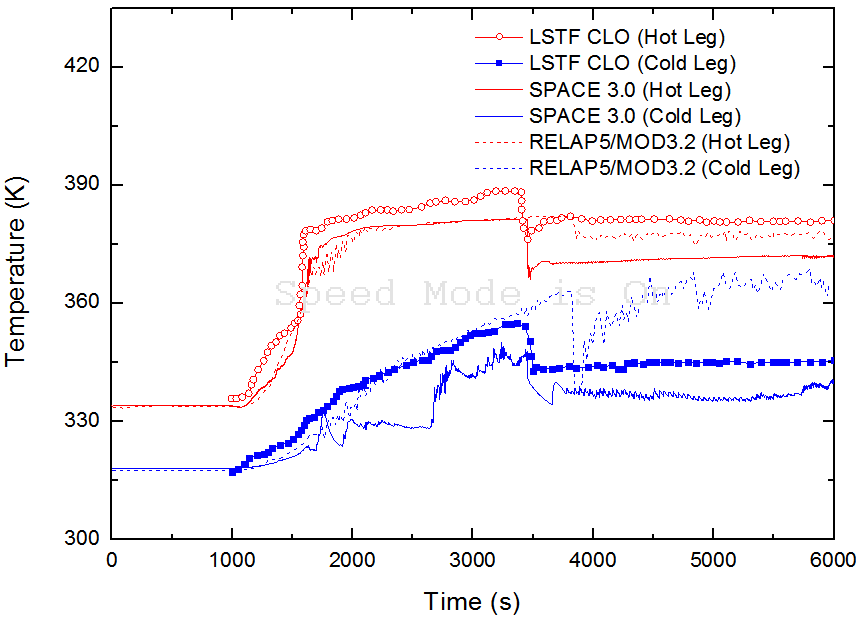

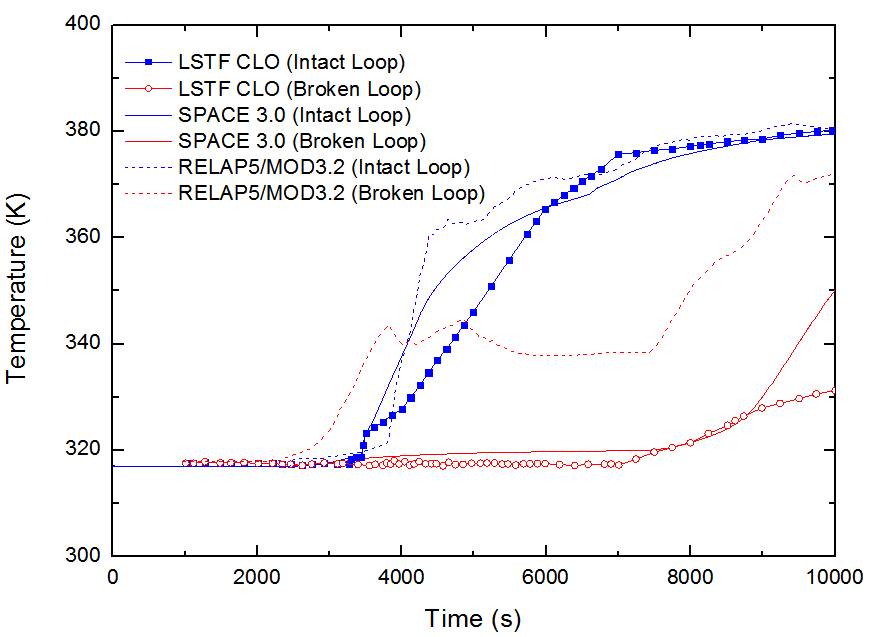

Figure 8 shows liquid temperatures in hot and cold legs in broken loop. After the saturation of steam in core upper plenum, the liquid temperature in the hot leg increased to the steam temperature in the experiment. Because the experimental data was measured at the ceiling of the horizontal pipe, the temperature was a steam temperature after the hot leg and cold leg were sufficiently voided. This results in the difference with calculated liquid temperature after the LSC.

Figure 9 shows liquid temperature in the bottom sides of the SG U-tubes. Because the SPACE code can well simulate the steam migration phenomena into SG U-tubes, the temperature behavior was similar with experiment than RELAP code.

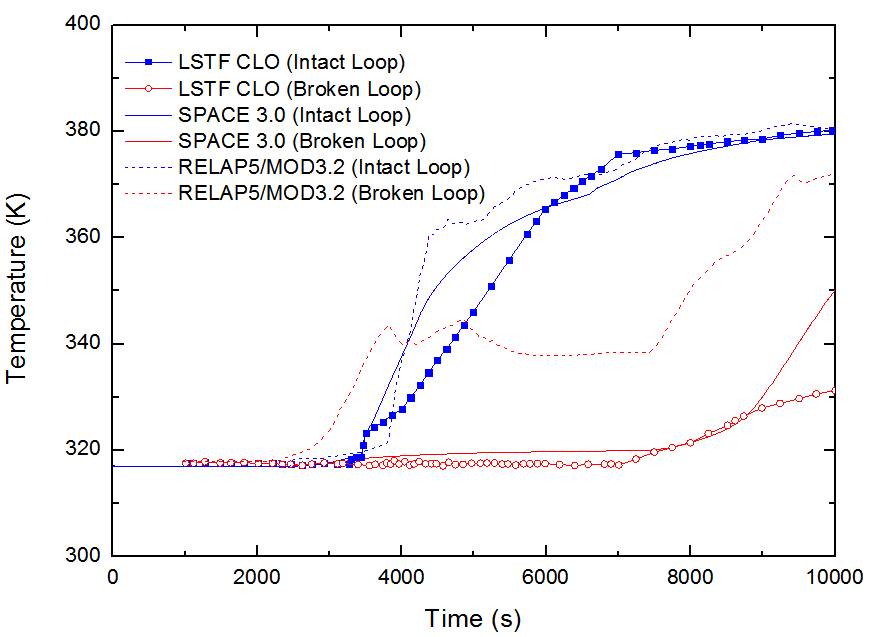

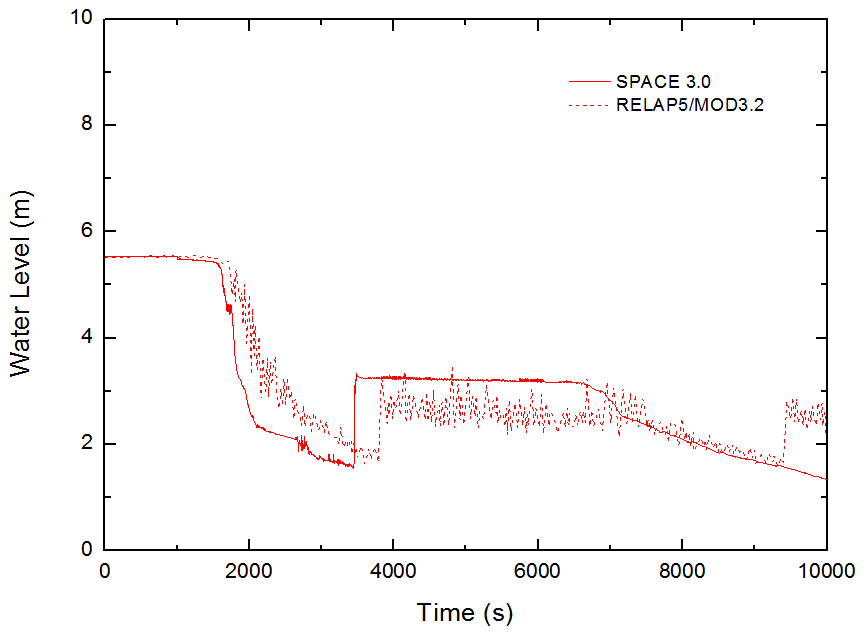

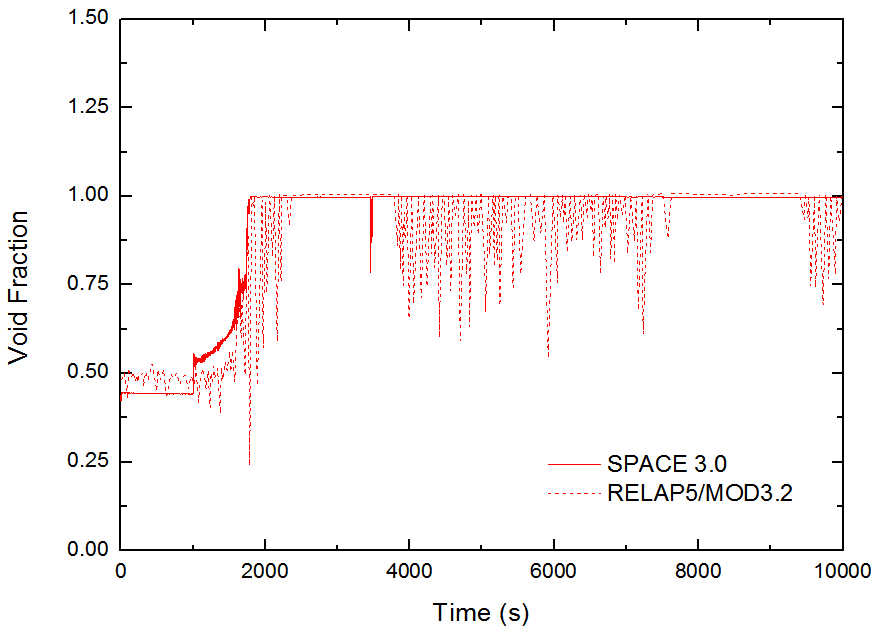

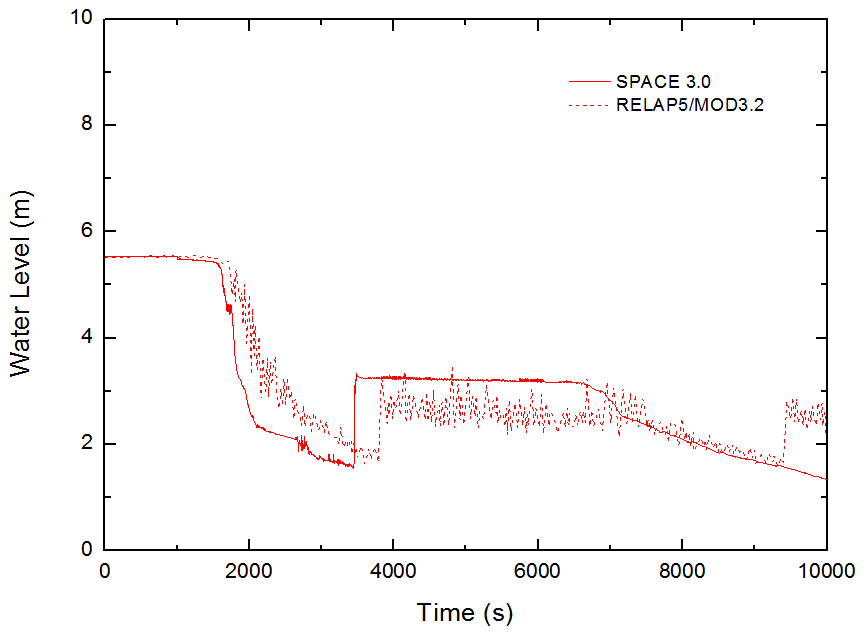

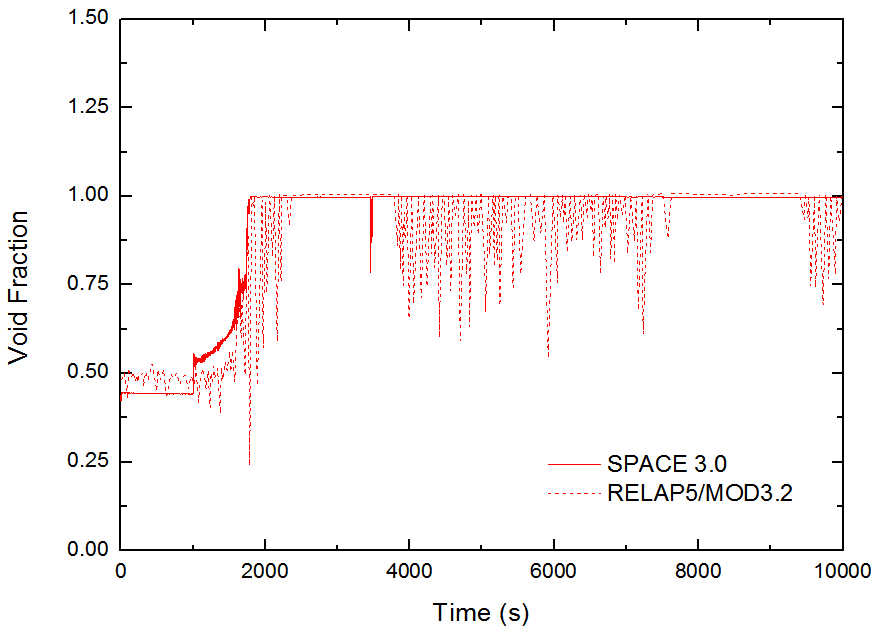

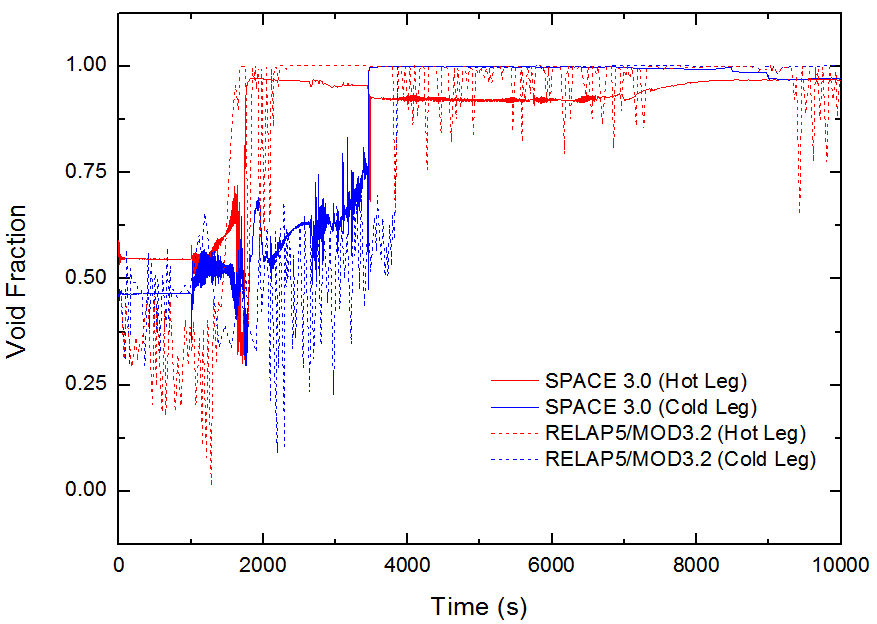

Figure 10 shows the collapsed water level of reactor vessel. Because the water level decreased, the hot legs and core upper plenum reach to the mid-water level in the early phase, as shown in Figures 11 and 12. When the LSC phenomena occurred, the cold legs became completely voided. The collapsed water level of the reactor vessel increased immediately following the water inflow from the crossover and cold legs.

V.Conclusion

The SPACE 3.0 code was assessed for the loss of RHR accident during the mid-loop operation in ROSA-IV/LSTF experiment. The major thermal hydraulic phenomena was compared with experimental data and RELAP code results.

Based on the results and comparison, it is observed that SPACE code shows good agreement with experimental data or overall parameters, and it is observed that SPACE code can effectively simulate during the transient.

VI.References

- Nakamura, J. Katayama and Y. Kukita, „RELAP5 Code Analysis of a ROSAIV/ LSTF Experiment Simulating a Loss of Residual Heat Removal Event during PWR Mid-Loop Operation,“ Proceeding of the 5th International Topical Meeting on Nuclear Reactor Thermal Hydraulics (NURETH-5), Vol. V, pp. 1333-1340 (1992)

- W Seul, Y. S. Bang, S. Lee, and H. J. Kim, “Assessment of RELAP5/MOD3.2With the LSTF Experiment Simulating a Loss of Residual Heat Removal Event During Mid-Loop Operation”, NUREG/IA-0143 (1998)

- J. Ha et al., „Development of the SPACE Code for Nuclear Power Plants,“ Nuclear Engineering & Technology, Vol. 43, No. 1, pp. 45 (2011)

Figures

Figure 1. Nodalization diagram for LSTF experiment

Figure 3. Calculated flow rate between guide tube and upper head

Figure 5. Differential pressure at crossover leg in intact loop

Figure 6. Differential pressure at reactor core

Figure 7. Liquid temperature in core

Figure 8. Fluid temperature at hot and cold leg in intact loop

Figure 9. Fluid temperature at steam generator secondary side

Figure 10. Collapsed water level in reactor pressure vessel

Figure 11. Void fraction in core upper plenum

Figure 12. Void fraction in broken loop

Table 1 Steady state calculation results

0 Comments