Effect of Bulk Condensation on Containment Athmosphere Mixing

SUMMARY

The impact of bulk condensation on the mixing dynamics of gases and flammability of the containment atmosphere is investigated in detail using OpenFOAM-based ‘containmentFOAM’ CFD package developed at Forschungszentrum Julich. The bulk condensation is efficiently modeled by bringing the local gas mixture to saturation temperature at a fixed timescale. The condensate droplets interact with the gas through latent heat exchange and are transported as a passive scalar by effects of convection, diffusion, and gravity. The model accounts for the changes in the size distribution of fog droplets, considering processes such as condensation, evaporation, and coalescence, all incorporated through the population balance model. The THAI HM2 simulations proved that bulk condensation has notable effect on the gas mixing behavior and local temperature distribution inside the containment.

INTRODUCTION

The condensation of steam amidst a Loss of Coolant Accident (LOCA) is an important phenomenon that limits the pressurization of a water-cooled reactor containment. With non-condensable gases present, steam condenses on the containment walls, forming rivulets and films, while simultaneously condensing in the bulk as fog. While the volume of bulk condensation remains relatively small in comparison to wall condensation, the formation of fog within the bulk and the subsequent re-evaporation of fog droplets, along with the release of latent heat, can affect the flow and mixing of the containment atmosphere. Hence, it is essential to model bulk condensation phenomena inside a reactor containment to predict the local gas and temperature distributions and to estimate probability of hydrogen combustion in an accident scenario.

A preliminary study considering bulk condensation in containment thermal hydraulics was conducted using a single-phase approach [1] to investigate the effects of bulk and wall condensation in CONAN (University of Pisa) and PANDA (Paul Scherrer Institute) experiments. The bulk condensation was modelled by removing the fog mass from the gas mixture and fog transport and its re-evaporation was neglected. However, the separate effect of bulk condensation on the containment conditions was not specifically addressed. Further studies by Zhang and Laurien [2] on the impact of bulk condensation on THAI TH2 simulation revealed that the transient vessel pressure and local temperature estimations were noticeably improved by considering bulk condensation. Here, a two-fluid approach was employed, distinguishing fog as a distinct phase from the gas mixture. This approach facilitated the monitoring of fog mass within the computational domain and allowed for potential evaporation. However, this approach is computationally expensive for technical scale applications considering the number of equations to be solved and additional models required for closure of the conservation equations. In order to run feasible multi-phenomena interaction simulations for large containments, George et al. [3] integrated the bulk condensation model [1] with a simplified Eulerian passive scalar fog transport mechanism featuring fixed droplet diameters. The model was incorporated into the OpenFOAM based containmentFOAM [4] solver which features containment relevant flow phenomena like turbulence, buoyancy-driven flow, gas radiation, multi-species transport and wall condensation. The simulations conducted on THAI TH2 demonstrated that the bulk condensation model notably enhanced temperature predictions within the vessel, particularly in the lower zone where the evaporation of fog led to cooling of the surrounding gas mixture. This would not have been possible without solving the fog transport equation considering the droplet drift mostly due to gravity where it was found that the droplet diameter had notable effect.

The objective of this study is to utilize the containmentFOAM solver with bulk condensation and fog transport to investigate the influence of bulk condensation coupled with other interactions on the containment atmosphere mixing process using OECD THAI HM2 (Becker Technologies, Germany) experiment [5] simulation. The fog transport model was extended with population balance method (PBM) to predict the droplet diameter by including droplet evolution by condensation growth and coalescence. The HM2 simulations indicated that bulk condensation has significant influence on the mixing behavior of containment gas as well as local temperature distribution.

METHODOLOGY

The transport of primary gas mixture comprising of two or more species is modelled by solving equations governing mass, momentum, species, and energy conservation, as detailed Kelm et al. [4]. To incorporate the impact of bulk condensation and evaporation, volumetric source/sink terms were introduced, modifying these governing equations [3].

Phase Change Modelling

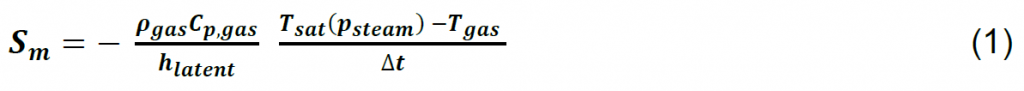

The rate of bulk condensation (or evaporation) is determined by utilizing an approach [1] based on driving the fluid in computational cell (element) to its saturation temperature using the latent heat released during condensation of the excess steam and absorbed during evaporation of the excess fog. In the current study, a key assumption regarding fog is that its droplets consistently maintain the same temperature as that of the local gas mixture. The phase change rate is computed using Eqn.1 and is also the source/sink term for the mass conservation equation. The exchange terms for closure of other conservation equations are described in Eqns. 2-4.

Mass transfer terms:

Momentum transfer term:

Species mass transfer term:

Energy (enthalpy) transfer term:

Here 𝜌𝑔𝑎𝑠 [kg/m3] is the density and 𝑇𝑔𝑎𝑠 [K] is the temperature of the gas mixture. 𝑇𝑠𝑎𝑡 [K] is the saturation temperature of the mixture at steam partial pressure 𝑝𝑠𝑡𝑒𝑎𝑚 [Pa]. The latent heat of vaporization is defined using ℎ𝑙𝑎𝑡𝑒𝑛𝑡 [J/kg] and Δ𝑡 [s] the time step size of a numerical simulation. Additionally, 𝐶𝑝,𝑔𝑎𝑠 [J/kg/K] and 𝐶𝑝,𝑠𝑡𝑒𝑎𝑚 [J/kg/K] are the specific heat capacities of the gas mixture and steam, respectively.

Turbulence within the primary gas flow is simulated using the standard 𝑘 − 𝜔 SST model. This model addresses transport equations governing turbulent kinetic energy 𝑘 and eddy frequency 𝜔, with 𝑆𝑘=𝑆𝑚𝑘 and 𝑆𝜔=𝑆𝑚𝜔 serving as the source/sink terms in instances of condensation or evaporation.

Fog Transport Modelling

The fog mass added or removed during phase change (condensation/evaporation) is not disregarded; instead, it is exchanged with a passive scalar field to predict its movement throughout the computational domain. The droplets get suspended in the gas, and transported to various locations within the containment where they can evaporate and deposit on the internal components and structures. Because

TS1 – Competence & Safety Page 3 | 6

of the distinct physical characteristics of fog compared to the gas, the droplets are prone to drift away from the primary flow path by the effects of gravity, inertia, drag and diffusion (turbulent and Brownian). This droplet drift velocity (𝑢⃗ 𝑑) is computed using Manninen model [7] by solving force balance equation for a droplet [3]. Taking into account all these interactions, the fog transport equation is formulated (Eqn. 5) for tracking the fog mass distribution and exchange with the primary gas mixture by condensation and evaporation. The volume fraction (αfog) variable is utilized in developing the transport equation, disregarding fog-fog interactions, and the influence of droplets on the primary flow which remains valid only for fog volume fractions below 1%.

Here, 𝐷𝑡 is the turbulent diffusion coefficient, 𝐷𝐵 is the Brownian diffusion coefficient and 𝜌𝑤𝑎𝑡𝑒𝑟 is the density of water which is assumed to be constant for a given simulation.

Population Balance Modelling

In the fog transport equation (Eqn. 5), it was found that the drift velocity (𝑢⃗ 𝑑) and Brownian diffusion (𝐷𝐵) is dependent on the droplet diameter and using a single fixed diameter may not be sufficient to predict the fog distribution correctly. The small diameter droplets nucleate near the steam release point and tend to follow the gas flow due to small drift velocities. These droplets then grow to larger ones by the effects of condensation and coalescence which have considerable drift velocity primarily due to gravity and traverse to the lower containment regions. Hence, to model these evolutions of fog droplet diameter, a population balance framework was used by having several droplet size groups. This is based on the method of classes model by Lehnigk [8] for polydispersed multiphase flows implemented in OpenFOAM. A transport equation like Eqn. 5 will be solved for each size group with its representative drift velocity and Brownian diffusion, and the groups interact with each other through mass transfer terms mainly due to coalescence, condensational growth and evaporational shrink. In the present study, the droplet breakup phenomenon was neglected to simplify the model. The bulk condensation mass source (𝑆𝑚) is distributed to all size groups based on the interfacial area of each size group.

Model Verfication and Validation

The models underwent separate verification and validation processes in previous research conducted by George et al. [3]. The bulk condensation and evaporation model was verified through a simulation, involving the mixing of hot and cold air, steam and fog mixture. The results showed strong concordance with Mollier diagram theory regarding both the gas temperature and the amount of steam and fog present. The validation of the droplet drift transport model was conducted through an analysis of aerosol flow within a bent pipe, specifically exploring the impact of the droplet Stokes number on deposition efficiency. The effectiveness of the phase change model was additionally confirmed and evaluated by integrating its interaction with other pertinent containment phenomena on the SETCOM [9] and THAI TH2 [10] experiments.

RESULTS

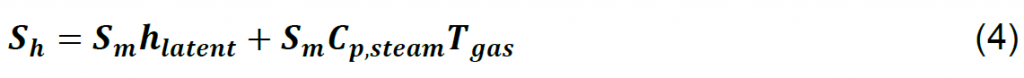

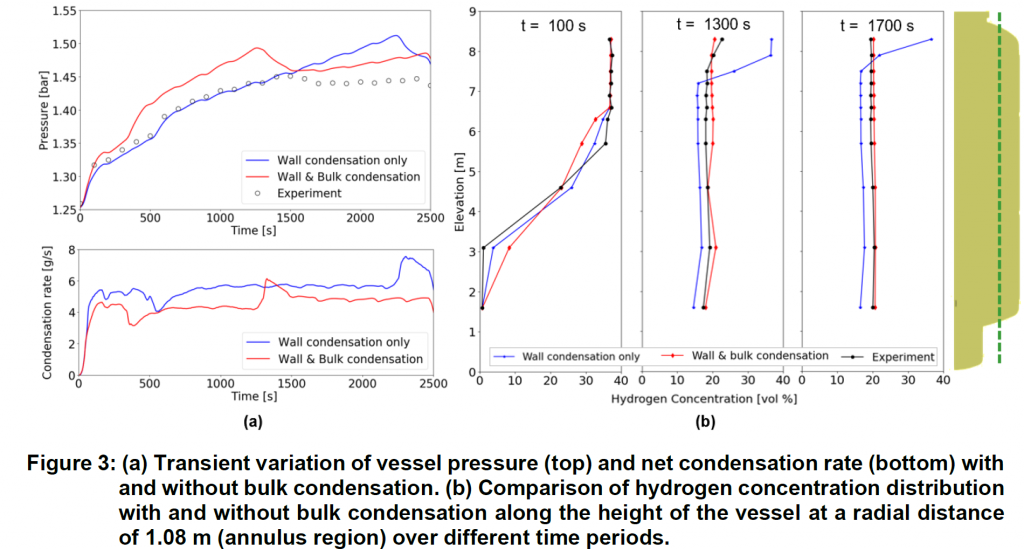

The impact of bulk condensation on gas mixing dynamics within reactor containment and the imperative need for its inclusion in CFD codes for containment thermal hydraulics are showcased through simulations of the THAI HM2 experiment [5]. The HM2 experiment is dedicated to studying the distribution and mixing behavior of hydrogen when steam is introduced into the vessel. Phase 2 of the experiment is simulated in which the hydrogen-nitrogen cloud in the upper vessel zone is gradually dissolved by injection of steam via a vertical nozzle at the lower vessel zone for a duration of 2500 seconds. The cross-section of the THAI HM2 vessel computational domain illustrating the internal components (inner cylinder, condensate trays), vessel wall and steam injection nozzle is shown in Figure 1a. Due to the quarter symmetry inherent in the vessel, the mesh (Figure 1b) was simplified to encompass only one-fourth of the domain, comprising a total of 0.5 million elements. The vessel was initially filled with a hydrogen-nitrogen mixture constituting a stratified layer of hydrogen with 40% concentration in the upper vessel zone, with gas temperatures ranging from 292 to 300 K, while the internal pressure measuring1.259 bar. The initial hydrogen (Figure 1c) and temperature (Figure 1d) distribution inside the domain is performed by interpolating the sensor data at different heights from the experiment.

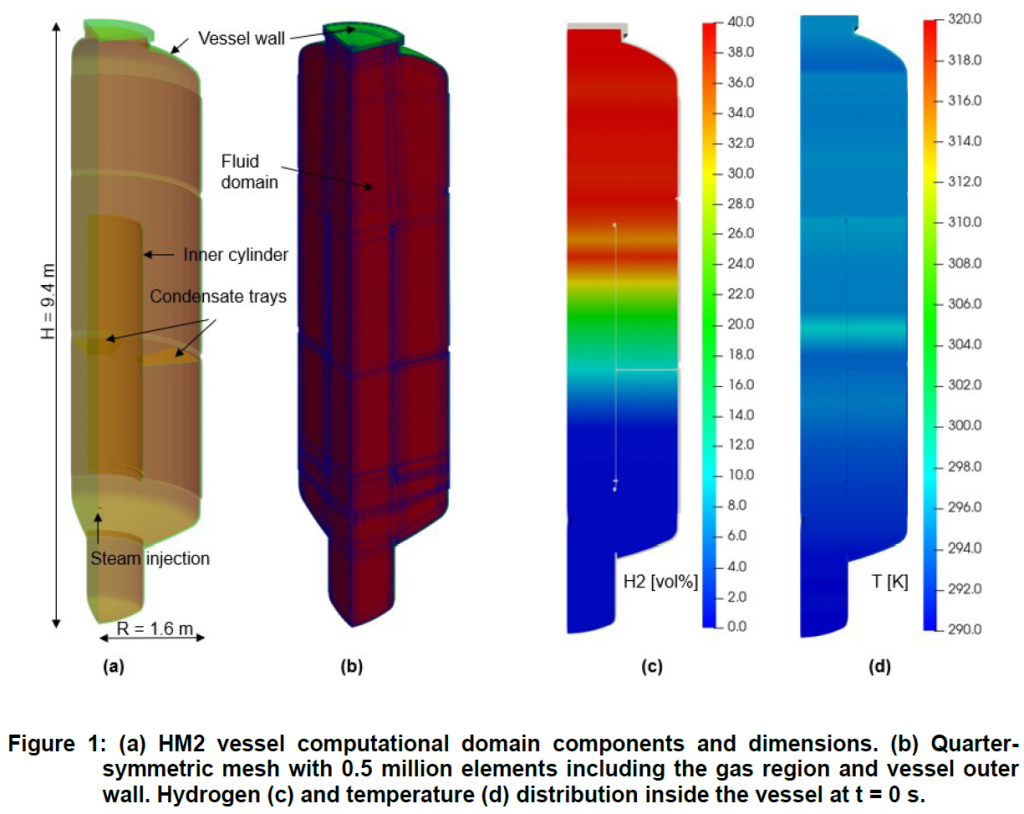

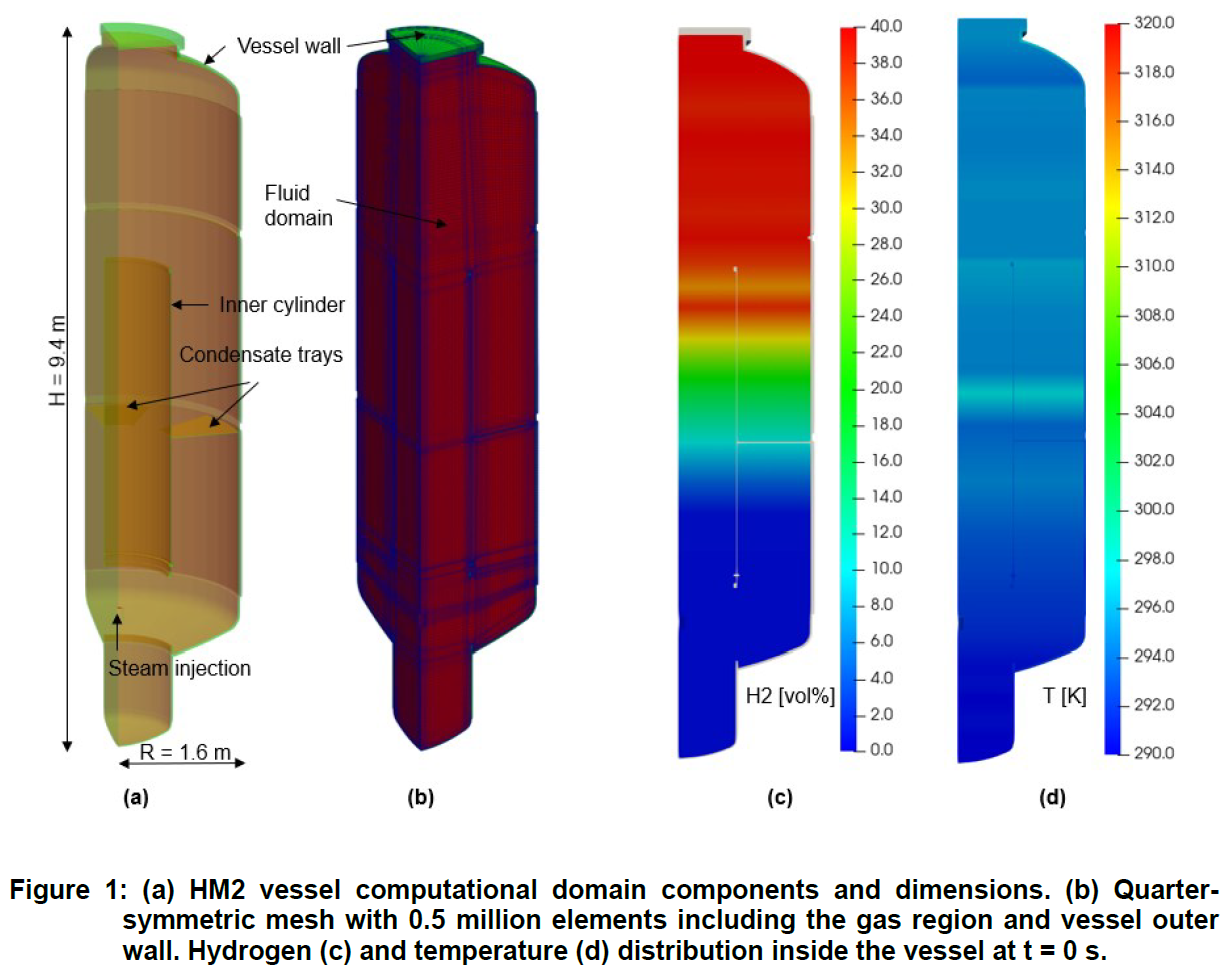

The simulations were run by considering wall condensation only and then by including bulk condensation to filter out fog effect on the conditions inside the vessel. Figure 2(a,b) shows the huge effect of bulk condensation on the temperature field especially in the inner cylinder zone. The bulk condensation of steam with associated latent heat release during the initial time (t = 100 s) increased the temperature by around 15 – 20 K which improved gas temperature prediction in the inner zone as confirmed by the vertical temperature distribution in Figure 2d. The fog formed primarily near the steam injection zone get distributed by the gas flow and drift in the inner cylinder region as illustrated in Figure 2c. The height-wise temperature distribution in the inner cylinder zone at different time intervals (Figure 2d) implies the improvement in temperature prediction accuracy of the simulation attributable to the incorporation of bulk condensation effects.

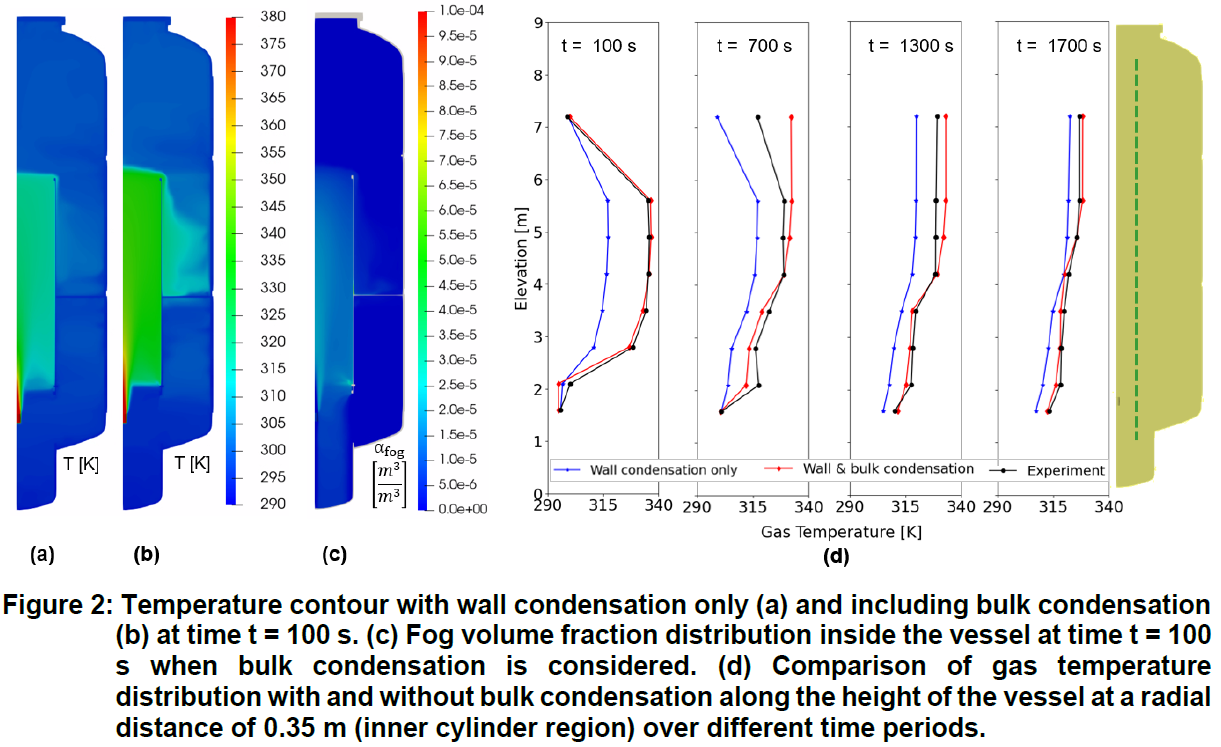

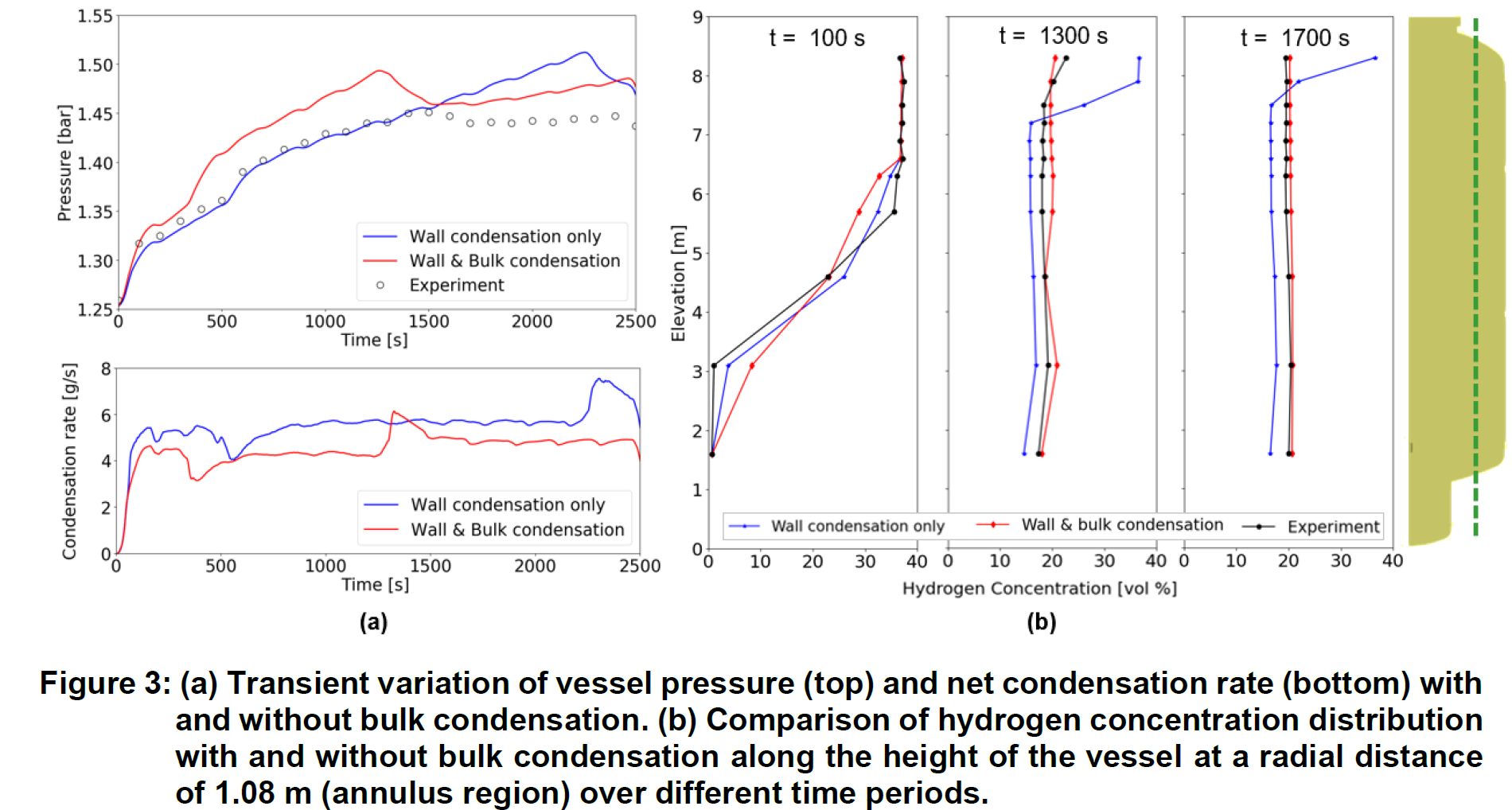

The transient variation of pressure (Figure 3a) shows better prediction (up to 1300 s) by excluding bulk condensation in terms of accuracy but the trend is better predicted by including bulk condensation. The sudden decrease in pressure at around 1300 s for the bulk condensation case is due to the rapid increase in condensation rate as shown in Figure 3a when the steam plume touches the cold wall of the dome intensifying wall condensation. However, by considering wall condensation only, the steam plume was able to reach the dome at around t = 2200 s which is inconsistent with the experimental observation. The timing of the steam plume arrival at dome is important from the containment mixing perspective as it completely dissolves the hydrogen cloud in the upper vessel zone. The hydrogen concentration distribution along the vessel height at different time intervals (Figure 3b) indicates that the hydrogen cloud dissolution phenomena was better predicted by considering bulk condensation. The is due to the latent heat release during fog formation which increased the mixture temperature (Figure 2b) inside the inner cylinder of the vessel , thereby increasing the buoyancy effects and enabling the steam to reach the dome much faster than without bulk condensation. Another significant finding from the simulations is that the overall condensation rate decreased (Figure 3a) when bulk condensation was included, as opposed to the scenario where only wall condensation was considered. This is also the reason why the pressure values are higher for bulk condensation case (Figure 3a) as more steam mass is present in the vessel due to decreased condensation rate. The two significant factors leading to lower condensation rate is the higher temperature in the inner vessel due to latent heat release during bulk condensation and the lower amount of steam available for wall condensation as some steam is already removed by bulk condensation. The key inference from the HM2 simulations is that bulk condensation has substantial effect on the containment gas mixing and local temperature distribution and hence, an important phenomenon to be considered while developing CFD models for containment atmosphere mixing and H2/CO risk mitigation.

CONCLUSION

With the present work an efficient bulk condensation model was implemented in containmentFOAM and applied to the THAI HM2 validation case. The simulations demonstrate the effect of bulk condensation, i.e. the change of density due to latent heat release as well as the change of the mixture composition. Thus, even though the bulk condensation impact on the water/steam balance is small compared to wall condensation it has substantial effect of the gas and temperature distribution. The simulations confirm the efficient and robust implementation of the model in containmentFOAM and motivate a further assessment in more application-oriented cases.

REFERENCES

[1] Vyskocil, L., Schmid, J., Macek, J., “CFD simulation of air–steam flow with condensation,” Nuclear Engineering and Design, 279, pp. 147–157 (2014).

[2] Zhang, J., Laurien, E., “3D numerical simulation of flow with volume condensation in presence of non-condensable gases inside a PWR containment” In: Nagel, W.E., Kröner, D.H., Resch, M.M. (Eds.), High Performance Computing in Science and Engineering ’14: Transactions of the High Performance Computing Center, Stuttgart (HLRS), Springer, pp. 479–497 (2014).

[3] George, A., Kelm, S., Cheng, X., and Allelein, H.-J, “Efficient CFD modelling of bulk condensation, fog transport and re-evaporation for application to containment scale,” Nuclear Engineering and Design, 401, 112067 (2023)

[4] Kelm, S., Kampili, M., Liu, X., George, A., Schumacher, D., Druska, C., Struth, S., Kuhr, A., Ramacher, L., Allelein, H.-J., Prakash, K.A., Kumar, G.V., Cammiade, L.M.F., Ji, R., „The tailored CFD package containmentfoam for analysis of containment atmosphere mixing, H2/CO mitigation and aerosol transport.” Fluids 6, 100. (2021)

[5] Kanzleiter, T., Fischer, K, Langer, G., „Helium/Hydrogen Material Scaling Test HM-2“. Report No. 150 1326 – HM-2 TR, Becker Technologies GmbH, Eschborn, (January 2008).

[6] Frederix, E.M.A., Kuczajd, A.K., Nordlundd, M., Veldmanc, A.E.P., Geurts, B.J., “Eulerian modeling of inertial and diffusional aerosol deposition in bentpipes,” Computers & Fluids, 159, 217–231. (2017)

[7] Manninen, M., Taivassalo, V., Kallio, S., “On the Mixture Model for Multiphase”. VTT Publications, 288, Technical Research Center of Finland. (1996)

[8] Lehnigk, R., Bainbridge, W., Liao, Y., Lucas, D., Niemi, T., Peltola, J., Schlegel, F., “An Open-Source Population Balance Modeling Framework for the Simulation of Polydisperse Multiphase Flows,” AlChE J., 68, 3 (2021)

[9] Kelm, S., Muller, H., Hundhausen, A., Druska, C., Kuhr, A., Allelein, H.-J., „Development of a multi-dimensional wall-function approach for wall condensation“. Nuclear Engineering Design 353, 110239 (2019).

[10] Kanzleiter, T., “Experimental Facility and Program for the Investigation of Open Questions on Fission Product Behaviour in the Containment (THAI=Thermal Hydraulics, Aerosols, Iodine)”. Technical Report, ThAI-Experiment TH2, Test Report to Reactor Safety Research Project No. 150 1218. (2002)

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors express their sincere gratitude to the German Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Energy for funding the national THAI-1 project (No. 150 1326) and to Becker Technologies (Eschborn, Germany) for their meticulous documentation and generous sharing of the THAI experimental data. Additionally, we extend our appreciation to the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD) for funding the PhD position through the ‚Research Grants – Doctoral Programmes in Germany.‘

AUTHORS

Allen George, Stephan Kelma, Xu Cheng

Institute of Energy and Climate Research, Forschungszentrum Jülich GmbH, Jülich, Germany, Institute for Applied Thermofluidics (IATF), Karlsruhe Institute of Technology, Karlsruhe, Germany

allen.george@partner.kit.edu, s.kelm@fz-juelich.de, xu.cheng@kit.edu

0 Comments